SEPT 23 — VRR is not an alternative to VAR in a football match.

VAR is Video Assistant Referee, which is a technology-aided officiating system intended to assist the on-field referees in a football match. However, critics say the technology is changing the sport for the worse.

VRR has nothing to do with a football match. It stands for Victim’s Right to Review. The following explains what VRR is.

In February 2006, the complainants, H and R, who both suffered from cerebral palsy, complained to the police of sexual assaults made upon them by one Christopher Killick. Subsequently, a complaint of non-consensual buggery of E by Killick in the early 1990s was then reported to the police.

Killick also suffered from cerebral palsy, though to an extent that was accepted to be considerably less than that of the complainants. In April 2006, he was arrested and interviewed.

He denied any form of sexual activity with the complainants. He accepted that he had had anal intercourse with H but said that it was consensual.

Although the arrest followed within a relatively short period of the making of the complaints, the decision on whether to prosecute was not made until June 2007, a year later, when the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) decided that Killick would not be prosecuted.

A complaint was then made of that decision which resulted in a review. The decision to prosecute was made in December 2009, three-and-a-half years after the arrest.

In the meantime, Killick had been told that he would not be prosecuted. The judge heard an application for Killick that the proceedings should be stayed for abuse of process.

Killick, through his counsel, contended that an unequivocal representation had been made to him that the matter would be dismissed.

He further contended that given the delay from the time of the two offences, which had allegedly taken place in the 1990s and what had happened, a fair trial was not possible.

In a careful and written ruling, the application was dismissed. The trial commenced in November 2010.

After the prosecution evidence had been heard, the judge held that there was a case to answer.

Killick did not give evidence. He was convicted of buggery of E without his consent and sexual assault on R. He was acquitted of the anal rape of H. He appealed.

The Court of Appeal of England and Wales (Criminal Division) took the opportunity to consider a victim’s right to a review of a decision not to prosecute and the extent to which the Draft European Union Directive modified English criminal procedure.

The Court of Appeal, having considered the Draft Directive, held that the “decision not to prosecute is in reality a final decision for a victim, there must be a right to seek a review of such a decision, particularly as the police have such a right under the charging guidance”.

The CPS had contended that the victims had no right to request a review of a decision not to prosecute but could utilise the existing CPS complaints procedure. Lord Justice Thomas, who delivered the judgment of the appellate court, said:

“[W]e can discern no reason why what these complainants were doing was other than exercising their right to seek a review about the prosecutor’s decision. That right under the law and procedure of England and Wales is in essence the same as the right expressed in Article 10 of the Draft European Union Directive on establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime dated 18 May 2011 which provides: ‘Member States shall ensure that victims have the right to have any decision not to prosecute reviewed’.” (See R v Killick [2011] EWCA Crim 1608 [49])

Having considered in some detail the right of a victim of crime to seek a review of a CPS decision not to prosecute, the Court of Appeal concluded as follows:

- a victim has a right to a review;

- a victim should not have to seek recourse to judicial review;

- the right to a review should be made the subject of a clearer procedure and guidance with time limits.

Following the judgement, the CPS created a new scheme – the Victim’s Right to Review (VRR) Scheme – to give effect to the principles laid down in the above case and also to meet Article 10 of the European Union Directive establishing minimum standards on the rights, support, and protection of victims of crime. It was launched in June 2013.

After the launch, the CPS undertook some work to see how the scheme was working in the light of experience. The outcome of this work was that a slightly revised, final, scheme of review was prepared and published in July 2014.

According to the CPS website:

“The Victims’ Right to Review (VRR) scheme enables victims to seek a review of certain CPS decisions not to start a prosecution or to stop a prosecution. It is an important safeguard in England and Wales in relation to the rule of law. The scheme was launched in 2013 and gives effect to the principles set out in the case of Killick (R v Christopher Killick [2011]). It is also an entitlement included in the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime.”

So, in the UK, there is not only VRR but also Code of Practice for Victims of Crime (Victim’s Code).

The latter focuses on victims’ rights and sets out the minimum standard that organisations must provide to victims of crime. It is issued by the Secretary of State for Justice under Section 32 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 after its presentation to Parliament in 2020 under Section 33 of the same Act.

Above all, there is the Code for Crown Prosecutors which is issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) under Section 10 of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985.

The Code sets out the general principles Crown Prosecutors should follow when they make decisions on cases.

The case of Killick was decided in 2011. The final VRR Scheme was published in 2014. The Victim’s Code is into its fourth year. The Code for Crown Prosecutors is already in its eighth edition.

Yet, there has been no reference to VRR and the Victim’s Code when concerns were raised relating to the alleged complaint of assault by Ong In Keong, the e-hailing cab driver, a person with disability, against a police officer.

The alleged incident took place in May 2024, about almost four months ago. Sadly, and regrettably until today, no prosecutorial action has been taken against the said police officer.

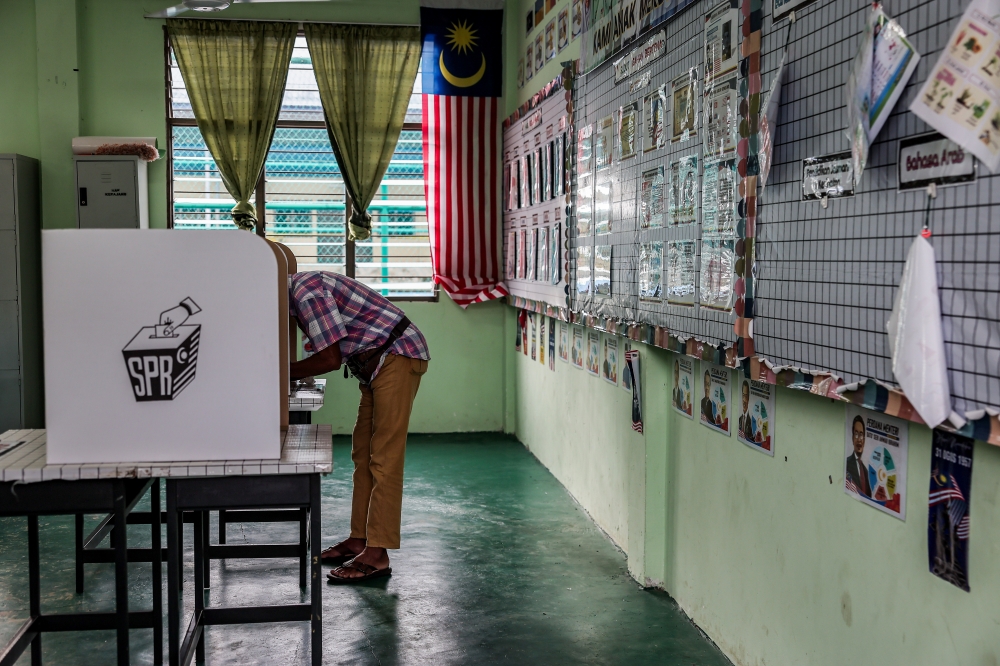

We can now call for institutional reforms of the office of the Attorney General (AG) cum Public Prosecutor (PP) to include not only the separation of the AG and the PP, but a Code for Prosecutors, VRR and Victim’s Code, among others.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.