SEPTEMBER 26 — Allianz, Adidas, Bosch, Mercedes-Benz, DHL, Faber-Castell, Hugo Boss and Nivea are familiar to us.

Fascinatingly, each of these world-famous German brands are not Berlin-based. Their headquarters are far removed from the capital.

These give credence to the notion wealth in Germany, or FRG (Federal Republic of Germany) is spread out. There are many other examples to support the claim, major cities like Munich (Bosch and Allianz), Hamburg (Nivea), Stuttgart (Mercedes) and Bonn (DHL) are richer per capita than Berlin.

Metzingen (Hugo Boss), Herzogenaurach (Adidas) and Stein (Faber-Castell) are towns under the radar, and yet homes to global consumer products.

Germany also practises firm autonomy and decentralisation policies for its states, towns and principalities.

This column posits the independence of the states and cities that have contributed massively to their successes.

The lesson’s instructive to discuss Malaysia, a federation with a different spread of economic activities.

Drive along the coastal road from Kuala Selangor to Butterworth, and witness the disrepair, disuse and disappointments in every small town, reminiscent of decay rather than Vision 2020. Sure, some spark at Penang Island and parts of Johor Baru, and then the euphoria ends.

Which begs the question, does Malaysia revolve too much around Kuala Lumpur?

Capitals are often nations' reference points — and critical economic zones — but when Malaysia’s broader potential appears hindered by Kuala Lumpur’s city lights, then one must take notice.

The unrestrained over-centralisation of power within the Klang Valley causes collateral damage — economic disempowerment elsewhere.

Or is the backwater label internal rather than caused by external factors led by the capital?

To suggest the castration of autonomy at the local level which actually stunts these towns and districts.

Render these units as mere functionaries of Putrajaya.

This column claims it is more of the latter, the inability of our towns and districts to lead their own futures.

That point of view is validated by the spectre of national leaders who descend upon areas for by-election campaigns and residents wait with bated breaths for goodies. A bridge here, a community hall there and the expected farm aid dished out.

See it at Tanjung Piai next month, when Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s party contests the by-election.

Therefore, perhaps the undoing is not as much as Kuala Lumpur being successful as much as forbidding Malaysian towns to chart their own courses.

A serfdom, when the people who live there are relegated to helplessness and left to only wish for a better future rather than to act.

Denying them, the right to be masters of their own fates

Outposts

Bentong Municipal Council (MPB) should be one of the richest towns since Genting Highlands’ casinos are within it. Why can’t towns prosper from their economic activities and conversely, punished when they are found wanting?

Where is the incentive for MBP to support the businesses on the mountain top if their annual grant is not tied to performance?

For MBP and all the other local authorities.

Presently, local councils carry out the will of the minister of local housing and government rather than that of the actual residents.

Absence of economic incentives is compounded by the absence of political will or autonomy.

Every arm of public delivery is under federal. The hospital, police, public works, civil defence under the ministries. Postal, electricity, telephony, broadband and cable TV under government agencies or friends of senior federal politicians.

Everything is primarily passed up to the Klang Valley. For ministers/agencies to collect information from all districts and then to redirect back to the districts the feedback.

Co-ordination meetings at local councils, I’ve attended them; these involve district police, medical officer, engineers, volunteer forces and TNB (electricity) / TM (Telecoms)/Water board reps.

They are counterproductive, ending up as sessions to troubleshoot and play safe, an euphemism for disengage.

They don’t intend to alter status quo.

Therefore most councils around the nation are purely reactionary and rely on federal government per se via the state government to produce results.

It’s cumbersome and produce low yields. Kuala Lumpur, on the other hand, and its satellites inside Selangor, benefit from distance to power.

On top of it, politicians live in the Klang Valley and they become de facto priorities.

Sense of destiny

Would tax-raising power and substantial control over local government arms/agencies/utilities at the local level, provide towns and districts with the platform to succeed?

It would most definitely allow the very unit to benefit or suffer from decisions to strengthen its local economy and delivery.

Parallels can be drawn from Selangor and Penang’s experience between 2008 and 2018.

When the states came under the then-Opposition, the new state governments had to work the situation from their states and cities, towns and districts rather than rely on Putrajaya.

In fact, they expected disruptions — which duly arrived through the federal government’s role. They become resilient from the trial by fire.

Selangor offered free tuition, more community funding, free buses and free health screening with the same pot of money, or less.

They targeted benefits and deliveries from the residents’ view. It is not that Khalid Ibrahim, and then Azmin Ali after him were geniuses but that power decisions, were decentralised and more decisions reflected what Selangor needed, and thereafter what Subang Jaya, Shah Alam and Kajang needed.

The proof is in the pudding, or at least the polling booth. From 36 seats in 2008, to 44 in 2013 to 52 (leaving six seats to Barisan Nasional) in 2018 for the evolving coalition. They kept getting more support, across all demographics.

Despite all the criticisms of DAP, Penang is a far more efficient state today.

The clamour for decentralisation of power is validated by Selangor and Penang’s decade-long experiences.

Putrajaya has too much power vested in it, and decentralisation of power is not merely a suggested strategy. It is a necessity.

Can Ipoh, Alor Setar, Pengkalan Hulu, Temerloh or Muar become more economically durable by possessing more power? It appears the question is never asked in the reverse.

Have these localities benefitted from their major decisions out of their hands — determined remotely and executed by their federally appointed local councils?

The answer is a resounding no. Then, why persist?

Forcing failed ideas on and expecting greater enthusiasm to catch any of the perennial shortcomings is foolish.

While power to a town does not guarantee success, the absence of power only ensures inactivity and insecurities for the town.

This column has carefully avoided mention of local council elections, because while the decentralisation of power works better with democratically elected administrators, they’d — any level of decentralisation — work far better than the present situation.

This is to allow the merits of decentralisation to be discoursed and not be thrown out with the local council election bathwater.

Our towns and districts are ailing. The time to expect edicts from Putrajaya to solve all our local problems is over. Any difficulty or challenge needs to be confronted at the local level by those there who feel the pain and understand the remedy.

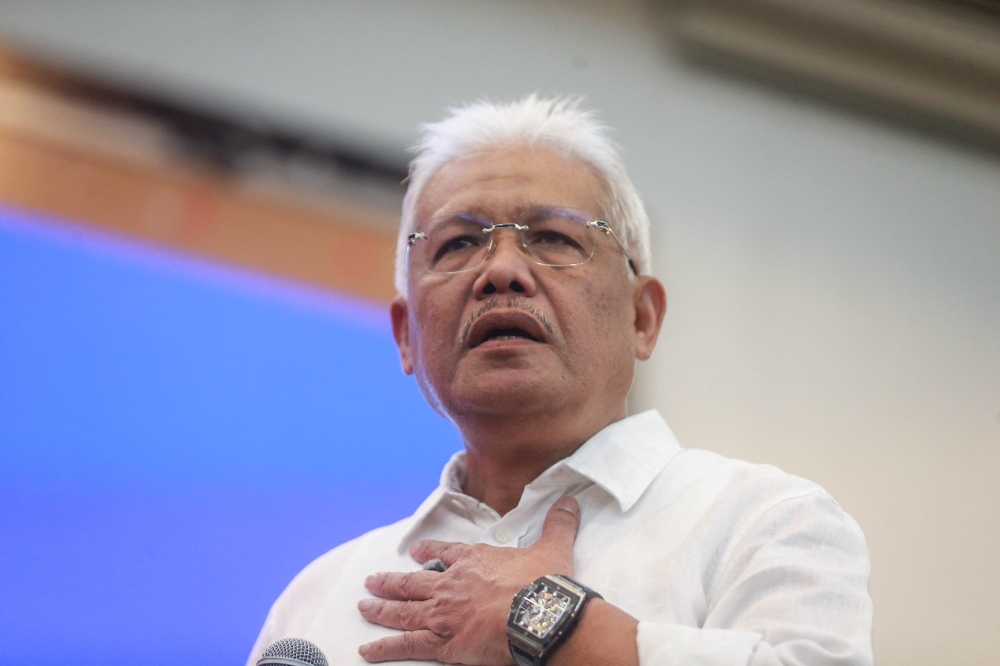

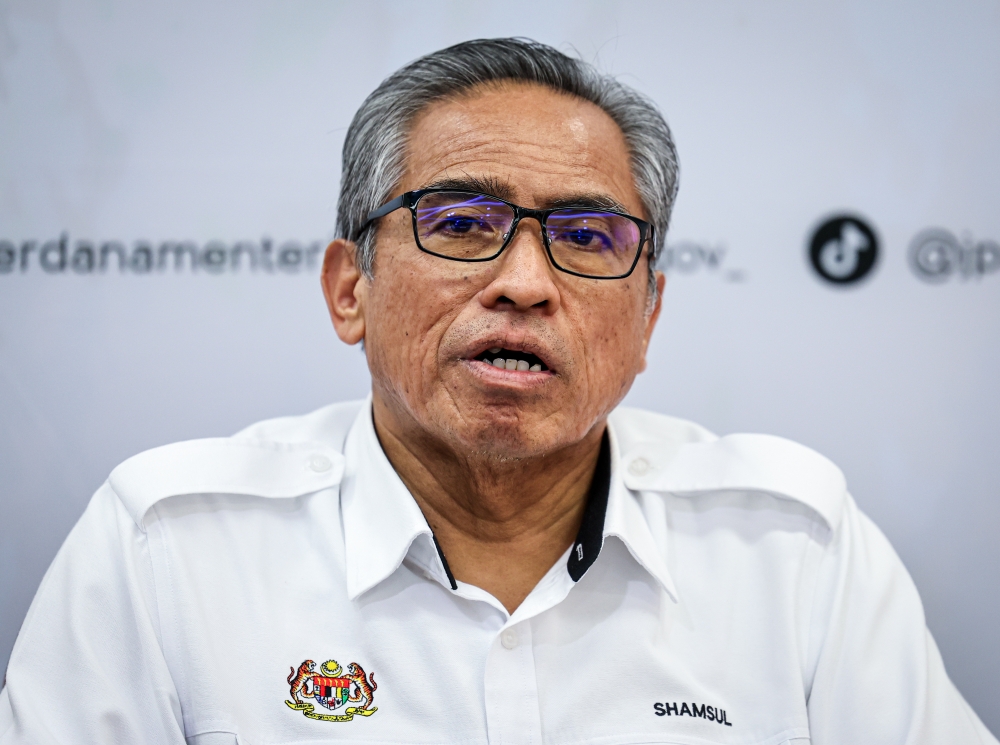

The economy and finance minister know these first-hand — as state leaders who localised power — and perhaps they should utilise their previous legacies to propel their future legacies.

Perhaps.

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.