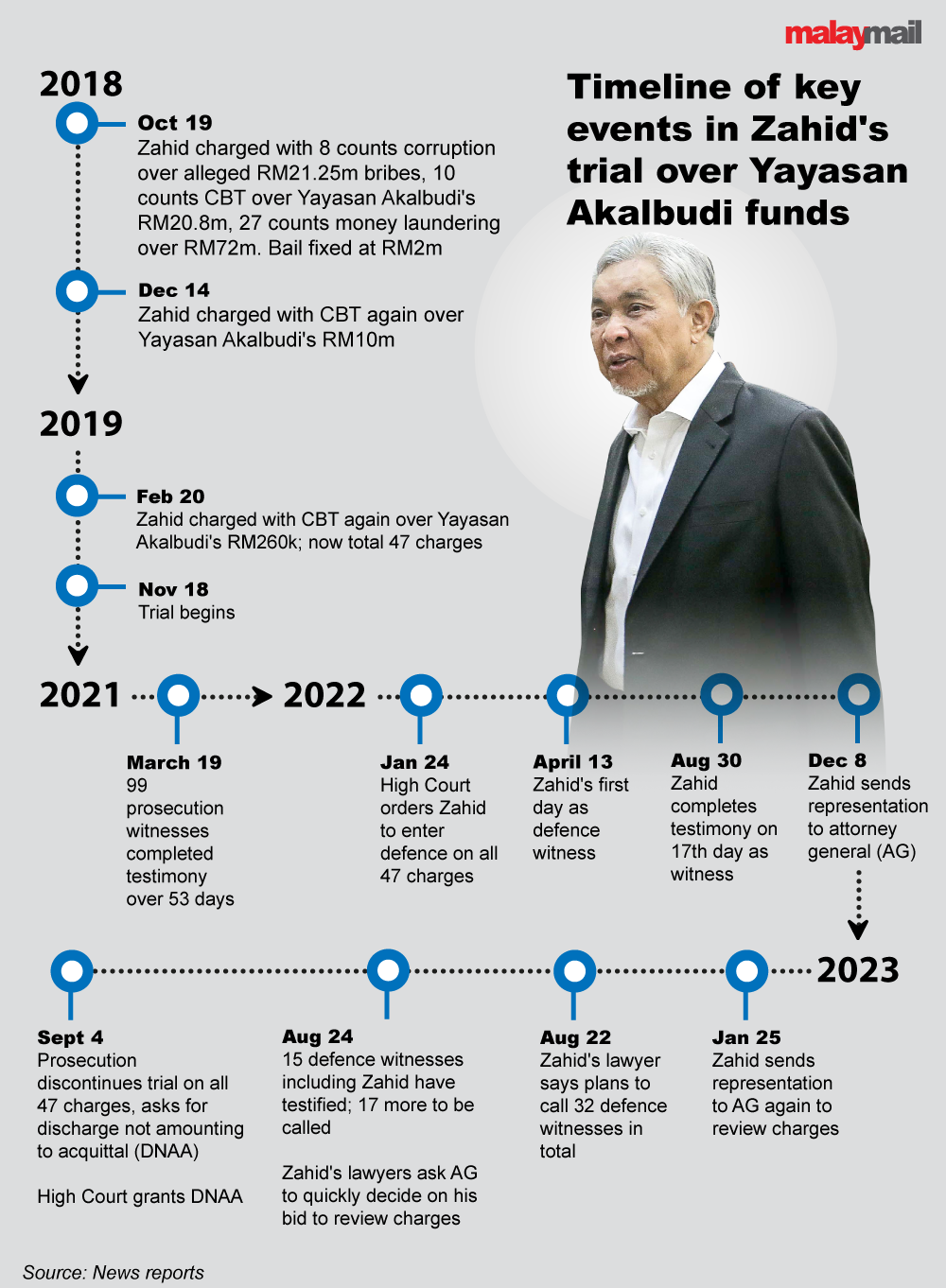

KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 8 — Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi’s release on Monday from all 47 charges in his Yayasan Akalbudi trial sparked a heated debate, but public discussion seems to be mixed up on whether it was the attorney general (AG) or the High Court’s decision to discontinue the trial.

Here’s what lawyers and a law academic explained to Malay Mail:

To put it simply, it’s almost like a two-stage process: where it is the AG who decides whether to discontinue an ongoing trial; and the court would then have to decide whether to grant DNAA or an acquittal since the AG has decided to discontinue the trial.

1. AG’s powers to discontinue the trial under Article 145 and Section 254

At the High Court, the prosecution on Monday said it wished to stop the proceedings on all 47 charges against Zahid, in line with Article 145 of the Federal Constitution and Section 254 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC). But the prosecution also asked for a discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA).

Ragunath Kesavan, a former Malaysian Bar president, said it is completely up to the AG to decide whether to discontinue a trial.

“Firstly, it is a complete and absolute discretion of the AG,” he told Malay Mail when contacted.

He said the courts have no powers to decide whether to initiate, continue or discontinue the prosecution of a case; adding that the courts would have no powers to refuse to stop a case once the AG has decided to drop the case.

“The court has no choice, the only thing the court would have done is either DNAA or acquittal. There’s no other option for the court.

“The court cannot say, ‘oh no, you can’t, you have to proceed with the case’. So I think there’s a lot of misconception to say it is a decision of the court,” he said when stressing that it is only the AG who has the power to discontinue a trial.

Mohamad Hafiz Hassan, a law lecturer at Multimedia University who teaches criminal procedure, said the public prosecutor is perfectly entitled under Article 145 to make the choice or decision to not further prosecute an accused person.

“Section 254 of CPC merely amplifies the powers of the public prosecutor, namely, the power to discontinue a criminal prosecution, as provided in Article 145 of the Federal Constitution,” he said.

2. Does the prosecution have to tell the court why the AG decided to discontinue the trial?

The short answer: No.

Ragunath said this is because it is the AG’s absolute discretion to decide whether to discontinue a trial.

Criminal lawyer Tiara Katrina Fuad said the AG is not legally required to explain his decision to withdraw charges which would result in a trial being discontinued, saying: “Because it’s his absolute power, so he doesn’t have to justify it to anybody.

“Legally, there’s no legal requirement which mandates that the AG provides reason before he can withdraw. But there are case laws which say after you withdraw, if you want a DNAA, that’s when you have to provide good grounds to justify the DNAA,” she said.

3. When would the AG decide not to continue with a trial?

Tiara Katrina said there are no written laws which state examples of situations where the AG would discontinue a trial, and there would also be no past court judgments analysing the prosecution’s reasons to discontinue the trial.

“When they withdraw, they don’t have to justify in court. So you are not going to find any case law which analyses their reasons, because it’s not within the scope of the court’s duties to analyse the reasons for withdrawal, only to determine whether it should be DNAA or acquittal.

“So if you are looking for case laws where the courts have said 'this is a good reason to withdraw, that is a bad reason to withdraw', you are not going to find it,” she said.

Asked if there might be written guidelines for when the AG decides to withdraw charges, she said it was not known if there are such guidelines internally within the AGC but said there are no publicly available documents on this.

She pointed to the United Kingdom’s Crown Prosecution Service, which does have publicly available standards for prosecuting and what the public prosecutor has to be satisfied with before charging.

But based on practice and standards of prosecution in other countries and principles of justice, Tiara Katrina argued there could be three reasons why the AG decides to discontinue a trial: when the accused is innocent, when the prosecution finds that there are no realistic prospects of conviction, or when there are policy considerations to justify a withdrawal of charges.

“So imagine a situation: a mother is charged with stealing a loaf of bread and there’s evidence to show she did that, but the reason she did that was because the child was starving and if she didn’t do that her child would die, there may be moral considerations, policy considerations not to prosecute her even though she’s technically guilty,” she said.

Ragunath again pointed out the AG’s absolute discretion to decide when to stop prosecuting a case, saying for example that it could be when there is a change of circumstances, when there is new evidence, or when the witness’ testimony during the course of a trial does not support the prosecution’s case.

Noting that there are no known written guidelines, Hafiz said an example of when the AG would decide to not continue with trial against an accused person is “where the public prosecutor requires a co-accused to give evidence for the prosecution against the other accused person”, as cited by the judge Wan Yahya in the 1982 case of Poh Cho Ching v. Public Prosecutor.

4. Can the AG drop the trial after a prima facie case has been proven?

Short answer: Yes.

Questions have been raised by the public on why the AG discontinued Zahid’s trial at a late stage of the case, which is after the High Court had ruled that there was a prima facie case and ordered Zahid to enter defence.

But what is a “prima facie case”?

Citing the CPC’s Section 180(4), Hafiz said a prima facie case is established when the prosecution has presented “credible evidence” to prove each ingredient of the offence which an accused is charged with, and which if unrebutted or unexplained by the accused would result in a conviction.

“So there was credible evidence in Zahid’s case. Otherwise, the trial judge would not call for the accused to enter his defence,” he said, adding that the accused would then have the burden of casting reasonable doubt on the prosecution’s case.

Hafiz said it is legally valid for the AG to drop the trial even when there is a prima facie case, noting that Section 254 states that the discontinuance of prosecution can be done at any stage of the trial before the court’s decision.

“But I think the public has the right to know why after the prima facie case, the prima facie case means there’s credible evidence, so the public prosecutor should in the interest of the public just let the case go on and let the defence raise reasonable doubt,” he said.

Tiara Katrina confirmed there is nothing in the laws to stop the AG from discontinuing a trial after the prosecution has proven a prima facie case.

“No, in fact the law is the opposite, it says at any stage of the trial (Section 254), he can inform the court that he doesn’t want to continue to prosecute the accused, so you can do that at any stage, including at the defence stage,” she said.

When the AG decides to withdraw charges at different stages of trials such as the early stages or later after the prima facie stage, the reasons that the AG would take into account would be different, she said.

“You may withdraw at the beginning of trial during the prosecution stage, because let’s say your witness has died and you can’t even meet your prima facie burden.

“But during the defence stage, you may withdraw for different considerations, you may say I have met my prima facie burden but now I have evidence that he’s innocent. Or now I know he’s going to raise this defence, I need to rely on this evidence to rebut it but the evidence is not available,” she said when giving examples.

Ragunath said the withdrawal of charges would mostly take place at the very early stage of proceedings.

“In extremely rare circumstances would there be withdrawal or discontinuance when defence has been called, because the rationale would be if the new evidence or whatever it is assists the accused, they can bring it up at the defence stage, because prima facie case has been found,” he said.

5. When the AG decides not to continue prosecuting an accused person, can the court reject this and order for the trial to continue?

Short answer: No.

Tiara Katrina said: “Because if you look at Section 254, once the AG withdraws the charges, once they say they don’t want to further prosecute, the court only has two choices: to DNAA or acquit. It’s couched in mandatory terms, the court must stay the proceedings, the wording is ‘shall’.”

Hafiz highlighted the High Court’s 1977 case of Public Prosecutor v Hettiarachigae LS Perera. In that case, the judge stated that the “courts have to wait” until the AG makes up his mind in relation to the AG’s Article 145 powers and that the courts have no business to usurp the AG’s functions. The judge also said only the AG has the power under Article 145 to institute, conduct or discontinue any court proceedings for an offence.

On Monday, the prosecution decided to discontinue and drop the Yayasan Akalbudi trial against Zahid — which resulted in the High Court granting a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) on Zahid for all 47 charges he faced.

Zahid, who is also Umno president and Barisan Nasional chairman, faced 47 charges in this case, namely, 12 counts of criminal breach of trust in relation to over RM31 million of his charitable organisation Yayasan Akalbudi’s funds, 27 counts of money laundering, and eight counts of bribery charges of over RM21.25 million in alleged bribes.

The move to not pursue the trial was derided by both sides of the political divide, with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim later stressing that he was not involved in the decision.

The Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) also defended its decision to discontinue the trial by saying that the prosecution had argued for a DNAA based on “cogent” reasons. In granting a DNAA in Zahid's case, the High Court had said the prosecution had given “cogent reasons” for why it applied for a DNAA.

The AGC's statement did not state why the prosecution decided to withdraw all 47 charges or to discontinue Zahid's trial.

This is Part 1 of Malay Mail’s series on how the law works for discontinuing of trial, discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA), acquittals and why institutional reforms are necessary. Part 2 will be published later today.