KUALA LUMPUR, April 3 — Decades after colonial rule, Malaysia has finally taken the first concrete steps towards abolishing the death penalty, after proposed legislation to make capital punishment optional and not mandatory was put before Parliament a second time.

The Abolition of Mandatory Death Penalty Bill 2023 was tabled for first reading in the Dewan Rakyat by Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said on March 27.

Azalina’s predecessor, Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, had tabled a similar piece of legislation on October 6, 2022, but Parliament’s dissolution to pave the way for the 15th General Election meant it was never put before lawmakers for debate.

“Legal amendments involving policies on punishment and substitute sentence to the mandatory death penalty are a positive change to make the country’s criminal justice system more holistic and inclusive, apart from not denying individuals their basic right to proper justice,” Azalina told the Dewan Negara days before the Bill’s tabled for the first reading.

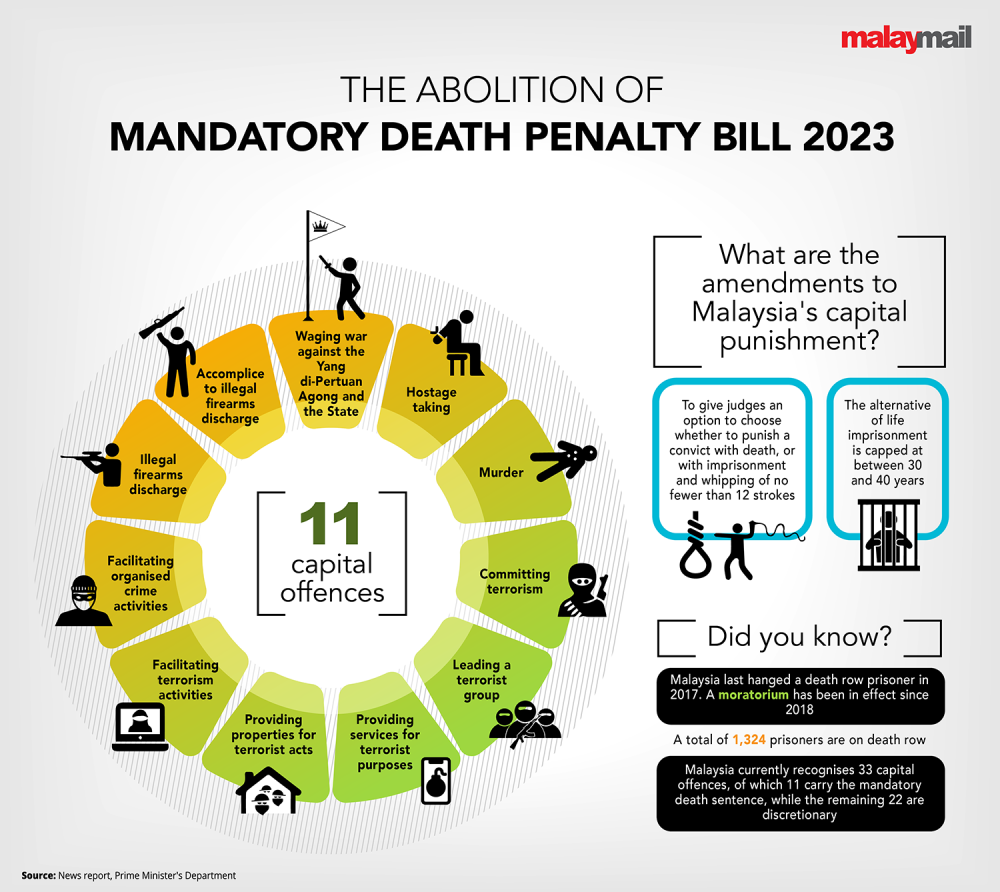

The current Bill seeks to revise the current death penalty by giving judges the discretion to mete out sentences on a case-by-case basis.

The amendments also include replacing life and natural life imprisonment (until death) as an alternative to the mandatory death sentence, with the new alternative of jail of between 30 and 40 years as well as no fewer than 12 strokes of the cane.

For the amendments to take effect, the Bill must obtain approval by way of three readings from both the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara, before being presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for royal assent and subsequently gazetted.

Since July 2018, Malaysia has placed a de facto moratorium on executions pending institutional reforms undertaken by the various administrations that have existed in that time.

The last death row prisoner was hanged in 2017 but because legislation carrying the mandatory death penalty has remained effective, the courts have been bound to continue sentencing defendants to death despite the moratorium on executions.

A brief history of Malaysia’s capital punishment

The death penalty has occupied a place in the Malaysian criminal justice system ever since British colonial administration, when the mandatory death penalty was originally enforced for murder.

When Malaya achieved independence in 1957, it inherited the common law system including the death penalty introduced during the reign of British Malaya.

Did you know the well-known Dangerous Drugs Act was enacted by the British colonial government in 1952 to combat the threat of substance abuse, yet capital punishment for drug trafficking — under Section 39B — was not carried out until 1975?

The death penalty remained discretionary for Section 39B up until 1983 when the legal provision was amended to make it mandatory, after which Malaysia’s drug laws would go on to be considered as among the harshest in the world.

Today in Malaysia, 34 offences such as murder, drug trafficking, waging war against the state and terrorism were punishable by death. Of those, 11 carried a mandatory death sentence.

Executions are performed as hanging by the neck until death, and usually conducted on Fridays.

At present, Malaysia is one of 53 countries worldwide that still maintain the death penalty in both law and practice.

What are the numbers?

According to the Prison Department’s latest data, a total of 1,318 prisoners were sent to the gallows between 1992 and 2023 for one of seven capital offences that carried the mandatory death penalty.

The capital offences listed are Section 121, 302 and 396 of the Penal Code for waging war against a Ruler, murder and gang-robbery with murder, respectively; Section 39B of the Dangerous Drugs Act for drug trafficking; Section 3 of the Kidnapping Act for abduction for ransom; and Section 3 and 3A of the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act for illegal firearms discharge.

The majority of the condemned — 870 of them or 66 per cent — comprised drug offenders, followed by convicted murderers at 318 or 24.1 per cent.

For the remainder, 16 were convicted for illegal firearms discharge, seven for waging war against the Agong, five for kidnapping, and two for gang-robberies.

Despite the movements to reform the death penalty, 2022 also saw the highest number of condemned persons at 123, of which 79 or 64.2 per cent were drug offenders followed by 44 or 35.8 per cent convicted of murder.

The Abolition of Mandatory Death Penalty Bill seeks to abolish the mandatory death penalty, to vary the sentence of imprisonment for natural life and whipping, and to provide for matters connected therewith by amending the Penal Code (Act 574), the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act 1971 (Act 37), the Arms Act 1960 (Act 206), the Kidnapping Act 1961 (Act 365), the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Act 234), the Strategic Trade Act 2010 (Act 708) and the Criminal Procedure Code (Act 593) in line with the Government policy to abolish the mandatory death penalty in all legislation.