KUALA LUMPUR, Feb 17 — The High Court today declared a 14-year-old girl — born in Ampang, Selangor to a Malaysian father and Myanmar mother and subsequently adopted by a Malaysian couple — as a Malaysian citizen.

The High Court decision comes after the child has spent 11 years making multiple attempts to be recognised as a Malaysian citizen. The child is due to turn 15 later this year.

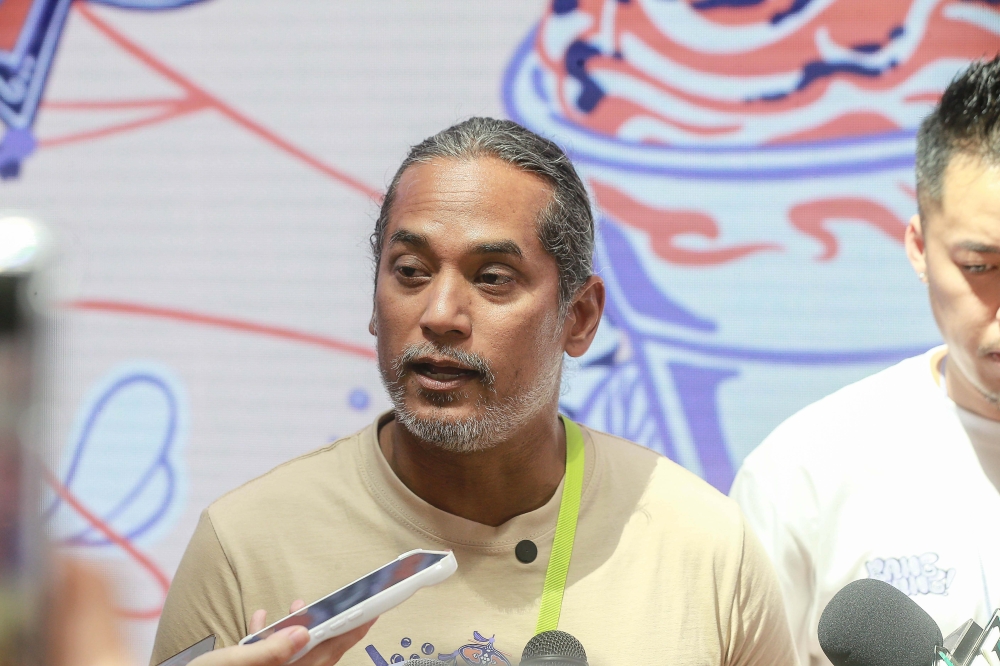

Surendra Ananth, one of the lawyers for the child, confirmed the decision earlier today by High Court judge Datuk Noorin Badaruddin.

“The High Court allowed our client’s citizenship application under section 1(e). The judge granted us a declaration to that effect and also granted two mandamus orders to compel the Respondents to change the citizenship status in the birth certificate and issue a blue IC,” he told Malay Mail, following the High Court’s hearing and decision earlier today through the video-conferencing platform Zoom.

In the interests of the child, Malay Mail is withholding the child’s name. For ease of reference, the child will be referred to as W.

On January 7, 2020, the child W along with her adoptive father had filed a lawsuit through a judicial review application, naming five respondents, namely the Registrar of Births and Deaths, the Registrar-General of Births and Deaths, the National Registration Director-General, the Home Minister and the Malaysian government.

This is the lawsuit that the child and her adoptive father won today in the High Court.

Lawyers Calvin Khoo and Gasper Wun also represented the child, while the respondents were represented by the Attorney General’s Chambers’ senior federal counsel Liew Horng Bin.

What happened in this case

Below is a summary by Malay Mail of what is known about this case, based on court affidavits filed as part of the lawsuit and other court documents:

The girl W was born in 2007 at a clinic in Ampang, Selangor to a Malaysian father and a Myanmar national mother, and was later formally adopted by a Malaysian couple through an adoption process at the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court.

The Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court in 2011 granted the adoption order and ordered a fresh birth certificate to be issued to identify the adoptive Malaysian parents as the girl’s parents. The fresh birth certificate was issued to recognise them as W’s parents, but stated W’s status to be a non-citizen of Malaysia.

In August 2011, W’s adoptive Malaysian mother applied for the child to be registered as a Malaysian citizen under Article 15A of the Federal Constitution, but this was dismissed on December 17, 2012 without any reasons given.

A second citizenship application was made also under Article 15A on August 4, 2014, but it was rejected three years later on December 12, 2017 without any reasons given.

The adoptive father said he appealed on July 12, 2018 against the rejection, but no decision has been made on the appeal. The child was due to turn 11 that year.

The child’s age is crucial as the pathway to be recognised as a Malaysian citizen under Article 15A comes with an age limit.

Article 15A provides that the federal government may register anyone under the age of 21 as a Malaysian citizen, “in such special circumstances as it thinks fit”.

The adoptive father in September 2019 and their lawyers in October 2019 wrote letters to ask the respondents to recognise the child W as a Malaysian citizen under Article 14(1)(b) read together with either Section 1(a) or Section 1(e) of Part II of the Second Schedule of the Federal Constitution within 14 days from the letters’ dates, but no reply has been received for such letters.

The Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b) provides that every person born on or after Malaysia Day and fulfilling any of the conditions in Part II of the Second Schedule is a citizen by operation of law — or automatically entitled under the law to Malaysian citizenship.

One of the conditions is Section 1(a) where a person born within Malaysia has to have at least one parent who is a Malaysian or a permanent resident in Malaysia at the time of the person’s birth, while Section 1(e) is the condition where the person born within Malaysia is not born a citizen of any country.

In January 2020, the child W and her adoptive father then filed the lawsuit, seeking for four court orders, including a declaration that W is a Malaysian citizen under Article 14(1)(b) read together with Section 1(a) and a similar declaration under Article 14(1)(b) read together with Section 1(e).

The two other court orders that W had sought for was for mandamus orders to compel the respondents to reissue her birth certificate reflecting her status as a Malaysian citizen within seven days of the court order and to issue an identity card with the status “Warganegara” (or “Citizen) to her also within seven days of the court order.

The High Court on February 26, 2020 granted leave for this judicial review, and proceeded to hear the judicial review today before deciding to grant three of the court orders sought — including the declaration of W as a Malaysian citizen under Article 14(1)(b) read together with Section 1(e). The judge did not grant a declaration of Malaysian citizenship under the Section 1(a) that W sought.

Surendra told Malay Mail that the judge also ordered the fresh birth certificate denoting Malaysian citizenship and for the MyKad to be issued but did not place a timeline for such issuance.

In an affidavit made on behalf of all respondents, National Registration Department (NRD) director-general Datuk Ruslin Jusoh said the child W was born illegitimate as her biological parents were not married at the time of her birth, and argued this meant she should take on her biological non-Malaysian mother’s citizenship instead of her biological Malaysian father’s citizenship.

Ruslin had also said the girl had to prove she is a stateless person that would qualify for Malaysian citizenship via Section 1(e), which requires a person born within Malaysia to not be born a citizen of any country and to not be a citizen of any country in order to be entitled to Malaysian citizenship.

The adoptive father in an affidavit responded that W was not born a citizen of Myanmar and is also not a Myanmar citizen.

The adoptive father said that Myanmar’s citizenship law (Pyithu Hluttaw Law No. 4 of 1982) does not confer Myanmar citizenship on a child born outside of Myanmar to a Myanmar national mother and a father who is not a Myanmar citizen.

Based on the written submissions by the Attorney General’s Chambers, one of its arguments was that Section 17 of Part III of the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule meant that the child W is entitled to her biological Myanmar national mother’s nationality.

Section 17 ― which applies to illegitimate persons and results in “father” or “parent” or “one of his parents” in the Constitution’s citizenship provisions being interpreted as referring to an illegitimate person’s mother ― is frequently used by the Malaysian government to argue that a Malaysia-born person cannot take on their Malaysian biological father’s nationality and have to take on their non-Malaysian biological mother’s nationality if they were not married when the person was born.

W’s lawyers in their written submissions, however, argued that Section 17 is not relevant to the girl’s case at all, as the Section 1(e) citizenship provision makes no reference to a person’s parents at all and is only revolving around the condition of being born in Malaysia while not being born a citizen of any country.

W’s lawyers said she is not born a citizen of any country including Myanmar and also does not hold a passport from any country.*Editor's note: An earlier version of this article contained an error which has since been rectified.