JANUARY 17 — The Federal Reserve Bank of the United States has never been a quiet institution.

From its birth in the early twentieth century to its present-day battles with presidents, markets, and foreign central banks, the Fed has always sat at the uneasy intersection of money and power.

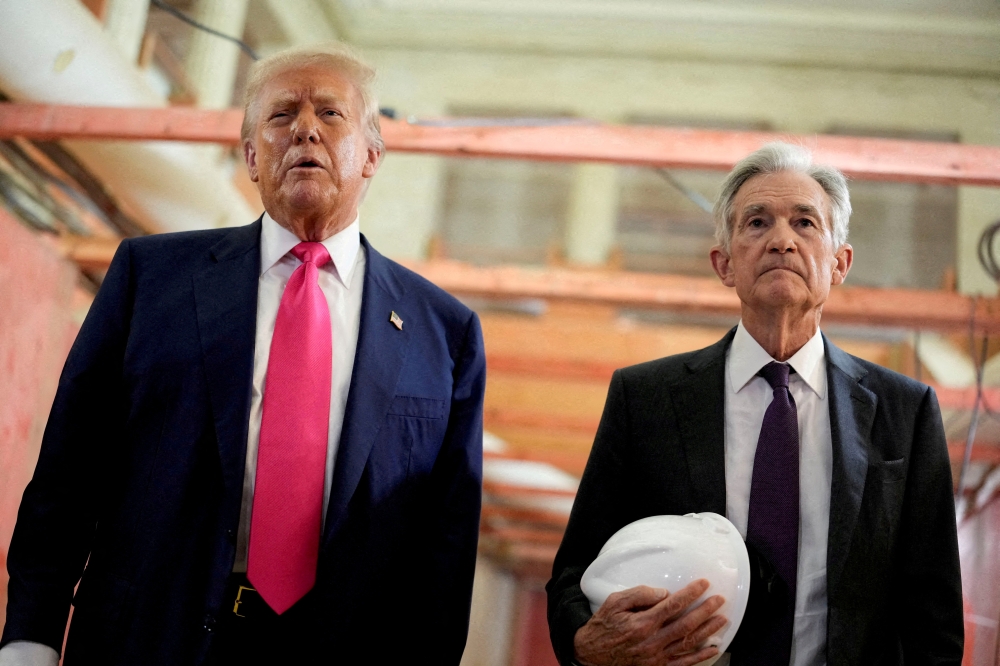

The latest tussle between President Donald Trump and the Chairman of the Federal Reserve (the Fed), Jerome Powell, once again exposes just how feisty and ferocious this institution can be when its authority is challenged.

Trump vs. The Fed: Power, politics, and accountability:

President Trump’s confrontations with the Fed have been unusually blunt. He has repeatedly accused the central bank of sabotaging growth by keeping interest rates too high or, at other times, of being slow and timid when aggressive rate cuts were needed.

What elevates this clash beyond the usual rhetorical sparring is the allegation of criminal wrongdoing.

Invariably, accusations that Chairman Powell misappropriated funds linked to the renovation of the Fed’s headquarters in Washington DC, with costs ballooning beyond the approved budget.

Whether such allegations hold legal weight is for investigators and American courts to decide.

Politically, however, they serve a clear purpose. Trump wants a lower interest to allow American consumers and his friends to enjoy a cheap cost of borrowing. Yet such interference of making the American economy by extension the world, worse off.

Trump’s attempt signals an effort by an elected executive to discipline, intimidate, or delegitimise an independent central bank.

It is to the credit of many central bankers to rally to the defense of Powell.

In fact, Powell, 74, could resign as the chairman and still serve another two more years as one of the fourteen federal bankers in the Fed. Indeed, to do ‘battle’ with Trump from the inside the system.

Powell could influence the rest of the Fed albeit no longer as the chairman, who believes that easy monetary policy facilitated by low interest is not the right way to go for the US economy.

It could lead to an excess of large domestic borrowings that lend themselves to over indulgent financial speculation; especially in the age of the AI sector.

Thus, Asean should watch the tussle between Powell and Trump carefully since the central banks in the region can be affected by the outcome of this duel between Powell and Trump in the Fed.

For Trump, however, the Fed is not merely a technocratic body; it is a powerful actor whose decisions shape elections, asset prices, employment figures, and ultimately political fortunes.

For the Fed, pushing back is almost instinctive. Its institutional culture prizes independence above all else.

Any suggestion that the White House can bend monetary policy through threats, prosecutions, or public shaming strikes at the very heart of its credibility.

A late comer in American finance:

What is often forgotten in these debates is that the Fed was not part of the United States’ original financial architecture.

Unlike the Bank of England, founded in the seventeenth century, the Fed is a relative latecomer.

The Federal Reserve System was created only in 1913, after repeated banking panics exposed the fragility of a system dominated by private banks and regional financiers.

Before 1913, the United States lurched from crisis to crisis.

There was no permanent lender of last resort, no unified authority to stabilise credit, and no coordinated response to bank runs.

The Panic of 1907, in which private financiers like J.P. Morgan had to personally orchestrate rescues, convinced political elites that relying on ad hoc heroics was no longer viable for a rising industrial power.

The Federal Reserve Act was thus a compromise. It created a central bank, but one deliberately fragmented and insulated from direct political control, reflecting America’s deep suspicion of concentrated financial power.

The twin mandate: Jobs and prices

From this cautious beginning emerged the Fed’s defining mission: its twin mandates.

Unlike many central banks that focus narrowly on inflation, the Fed is legally tasked with keeping unemployment low while also containing inflation.

This dual responsibility makes it both more powerful and more politically vulnerable.

To fulfill this mandate, the Fed manages the money supply primarily through interest rates.

By raising rates, it cools borrowing, spending, and inflation. By cutting rates, it stimulates credit, investment, and employment. But the likes of Powell is there to make sure the American economy can all work in synchronicity.

These decisions ripple through housing markets, stock exchanges, currency values, and government debt.

This is why presidents care so deeply about the Fed. Monetary policy can either amplify or blunt fiscal policies.

But US to try to push for a lower interest rate policy can be potentially catastrophic too.

Since lower interest can usher in an era of wild borrowings and spending.

It can make a boom look stronger or a slowdown feel harsher.

In electoral terms, it can shape the public mood more decisively than many laws passed by Congress.

From national referee to global conductor:

Over time, the Fed has grown far beyond its original domestic remit.

The US dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency has turned the Fed into an informal global central bank.

When the Fed raises or lowers rates, capital flows surge or retreat across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America.

Through swap lines, coordinated interventions, and crisis management, the Fed has helped create a chain of central banks working together, often in its shadow.

During global crises, other central banks look not just to Washington DC but specifically to the Federal Open Market Committee for signals. Will the rates be reduced and how often this year ?

This dominance means that the Fed’s decisions can determine the fate of emerging markets, shape debt sustainability abroad, and even influence political stability in distant regions.

Independence under siege:

This global reach makes domestic political attacks on the Fed even more consequential.

A central bank perceived as politically captured risks losing credibility at home and abroad. Markets price independence.

Other central banks coordinate with the Fed precisely because they believe it operates on rules, data, and institutional judgment rather than presidential whim.

The clash between Trump and Powell therefore reflects something deeper than personal animosity or budgetary disputes.

It is a struggle over who ultimately governs money in the world’s most powerful economy: elected politicians driven by short-term imperatives, or an independent institution designed to think in longer cycles.

A necessary tension:

The Federal Reserve was born late, forged in crisis, and empowered cautiously. Its feisty resistance to political pressure is not an accident but a design feature.

Yet that very independence ensures it will always be contested, especially by presidents who view economic performance as inseparable from political survival.

In this sense, the Fed’s ferocity mirrors the ferocity of American capitalism itself.

It is a latecomer that learned quickly, a technocratic institution with immense political consequences, and a central bank whose influence now binds not just the United States, but much of the global financial system, into a single, tightly wound monetary order.

* Phar Kim Beng is professor of Asean Studies and director of the Institute of International and Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.