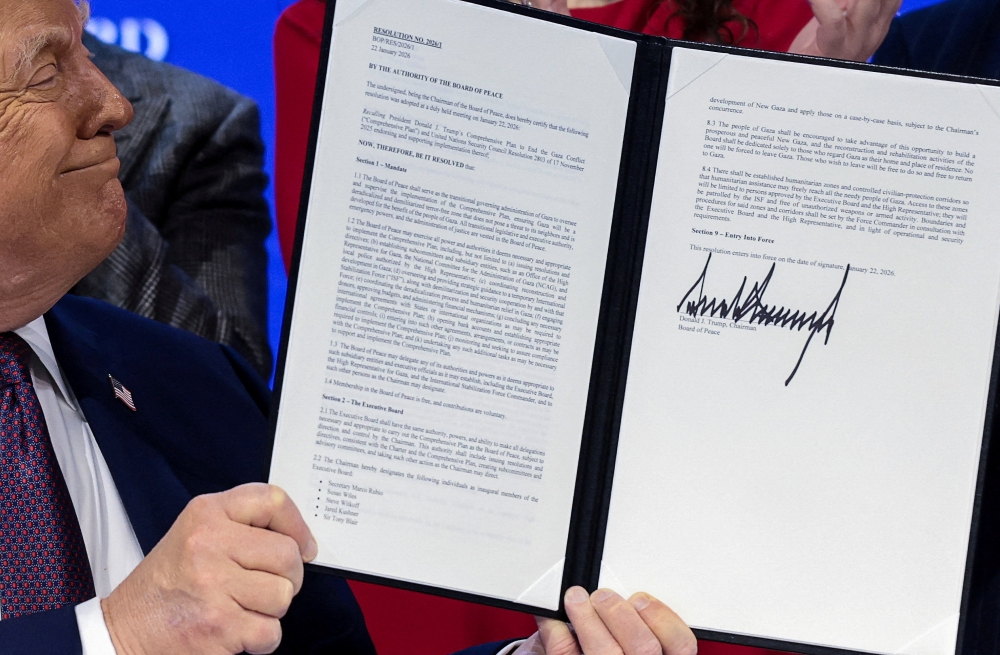

PHNOM PENH, Oct 14 — When the United States and the United Kingdom jointly imposed sanctions on a Cambodian-led network accused of trafficking, scamming, and laundering billions through Bitcoin, it marked a turning point in how we must now understand war, crime, and technology. The case, involving the seizure of more than US$15 billion (RM63 million) worth of Bitcoin, exposed how Southeast Asia’s digital fringes have become a theatre of financial and psychological warfare — a battleground without borders, soldiers, or uniforms.

What began as a story of forced labour and online fraud in Cambodia’s Sihanoukville has morphed into something far more sinister: a demonstration that the same algorithms designed to decentralise wealth can destabilise nations, corrupt governance, and underwrite conflict.

The invisible battlefield

Cryptocurrency was conceived to democratise finance — to free the individual from the tyranny of central banks. But the utopia has soured. Cambodia’s scam syndicates reveal a darker reality: that the same blockchain that promises transparency has become an opaque shield for human exploitation.

In these compounds, thousands of trafficked workers — many from China, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Vietnam — were reportedly forced to work endless hours conducting “pig-butchering” scams: building trust with victims online before draining their savings through crypto investments. Torture, confinement, and even killings were allegedly used to enforce discipline. Each stolen Bitcoin or Tether token thus becomes not merely a line of code, but a unit of suffering.

Yet what makes this more dangerous is scale and reach. Those digital coins, once laundered through privacy mixers and cross-chain exchanges, can finance private armies, buy political loyalty, or manipulate real-world markets. A war funded by Bitcoin requires no guns — only servers, social engineers, and complicit elites.

From digital crime to geopolitical threat

The Cambodia case exposes how fragile the boundaries are between criminal enterprise and state complicity. The sanctioned figures — many with ties to ruling circles — exemplify the new face of corruption: one that fuses criminal innovation with bureaucratic protection.

Such patterns mirror other parts of the world where warlords, militias, or intelligence services exploit crypto anonymity to bypass sanctions or acquire weapons. As Washington and London froze wallets and properties tied to Cambodian ringleaders, they exposed not only a criminal empire but also the architecture of a new type of financial warfare — one that can destabilise whole regions by stealth.

The geopolitics are equally unsettling. Cambodia sits strategically between Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, and has courted vast Chinese investment. The rise of crypto-funded networks there threatens not just public order but Asean’s credibility as a rules-based community. When illicit crypto economies entrench themselves in member states, Asean’s entire digital integration agenda — from cybersecurity to cross-border payments — becomes compromised.

Bitcoin and the architecture of violence

Wars of the future will not necessarily begin with invasions. They may start with financial infections.

Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other decentralised assets allow capital to move frictionlessly across borders, but also beyond the grasp of regulators. When hostile actors — whether hackers, mercenaries, or foreign proxies — exploit this feature, they can fund cyberattacks, information warfare, and mercenary operations without traceable financing.

Cambodia’s scam centres are thus a prototype of how criminal networks evolve into paramilitary digital economies. The scamming compounds, guarded by armed men and equipped with advanced computing, are microcosms of cyber-militarised zones. They convert stolen wealth into political influence, purchase weapons and security, and create local dependencies through employment and patronage.

In short, Bitcoin has become the fuel of a shadow war — one that blurs crime, commerce, and conflict.

Regulatory blind spots and Asean’s dilemma

Traditional financial safeguards — Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) rules and Know-Your-Customer (KYC) protocols — were built for banks, not blockchains. Regulators can freeze bank accounts, but not private keys stored in digital wallets. By the time enforcement agencies trace illicit funds, they may have been converted into property, art, or influence.

For Asean, the lesson is urgent. The bloc’s pursuit of a unified digital economy must be matched with a regional crypto-regulatory framework. Otherwise, digital transformation will outpace digital security. Cambodia’s experience is not isolated: similar scam compounds exist in Myanmar’s borderlands, Laos’s special zones, and potentially Thailand’s northern grey markets. Together, they form a regional triangle of cyber-exploitation — a ticking humanitarian and political time bomb.

Malaysia, as Asean Chair in 2025, must lead efforts to establish a regional digital-finance task force — combining the expertise of central banks, financial intelligence units, and law-enforcement agencies. Without collective surveillance and enforcement, digital forays into Bitcoin will continue to breed instability.

Humanitarian fallout and social erosion

The victims of Cambodia’s scam empire are not limited to those scammed online. The trafficked workers — deceived by job ads and then enslaved — embody the collapse of human security in the digital age. Their stories of starvation, electrocution, and confinement expose the hollowness of narratives that celebrate crypto riches and “innovation without borders.”

Beyond the moral dimension lies a civic one. When billions flow through shadow networks, national tax bases erode, inequality widens, and legitimate enterprise suffers. In fragile democracies, illicit digital finance can warp elections and media landscapes, empowering those who manipulate capital without accountability. The same algorithms that made global finance efficient are now enabling authoritarian resilience.

A call for financial disarmament

To prevent “wars fuelled by Bitcoin,” governments must rethink the meaning of deterrence. Sanctions, seizures, and arrests are necessary but insufficient. The real solution lies in financial disarmament — cutting off the channels through which digital wealth funds violence.

This requires a coalition beyond the West. Asean, the Gulf states, and East Asian partners must build interoperable monitoring systems to track crypto flows, share intelligence, and regulate mining operations. Exchanges operating in the region must adopt blockchain-forensic compliance as standard practice. Tech companies must share metadata on suspicious wallet activity, while universities and think-tanks should research crypto-related conflict financing.

Equally, public education is vital. The victims of scams — from retirees in London to students in Kuala Lumpur — are the unwitting sponsors of digital slavery. Awareness campaigns must treat crypto scams not merely as financial crimes but as human-rights violations.

Conclusion: Code and conscience

The Cambodia Bitcoin saga is more than a criminal case; it is a parable about our times. The decentralisation of finance, once hailed as liberation, now risks becoming the scaffolding of new authoritarianism and violence. When code becomes unmoored from conscience, even innovation turns lethal.

Wars in the twenty-first century will not only be fought over territory, ideology, or religion. They will be fought over trust — and those who control digital trust will control power itself.

Cambodia’s digital foray into Bitcoin has revealed that without moral restraint and international oversight, even a few lines of encrypted code can ignite conflicts far beyond our imagination.

The world must act before this invisible war consumes us all.

* Phar Kim Beng, PhD, is a professor of Asean Studies and director of the Institute of Internationalization and Asean Studies (IINTAS) at the International Islamic University Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.