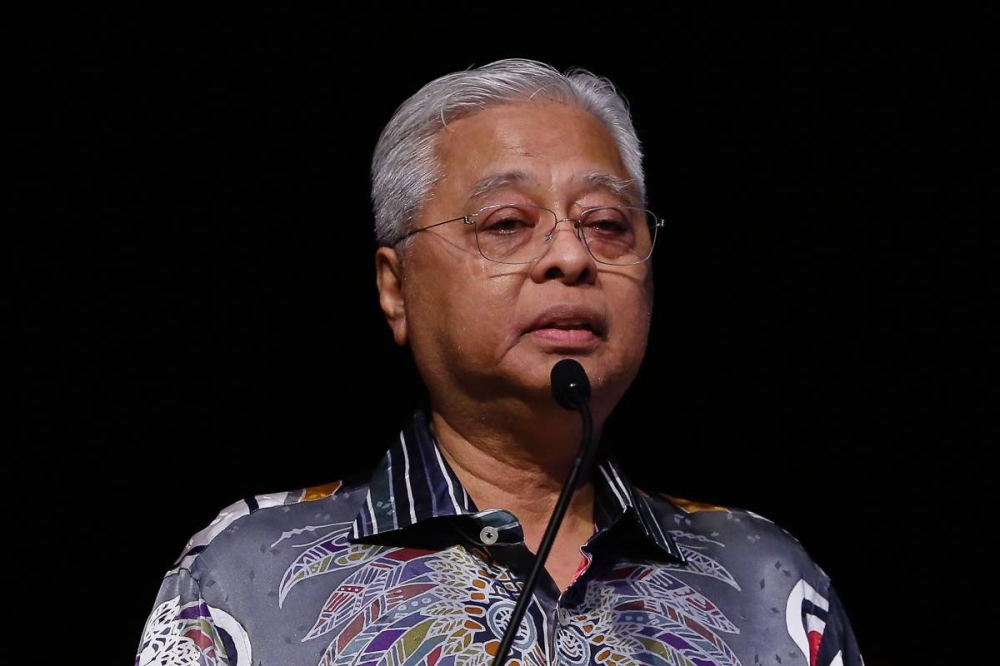

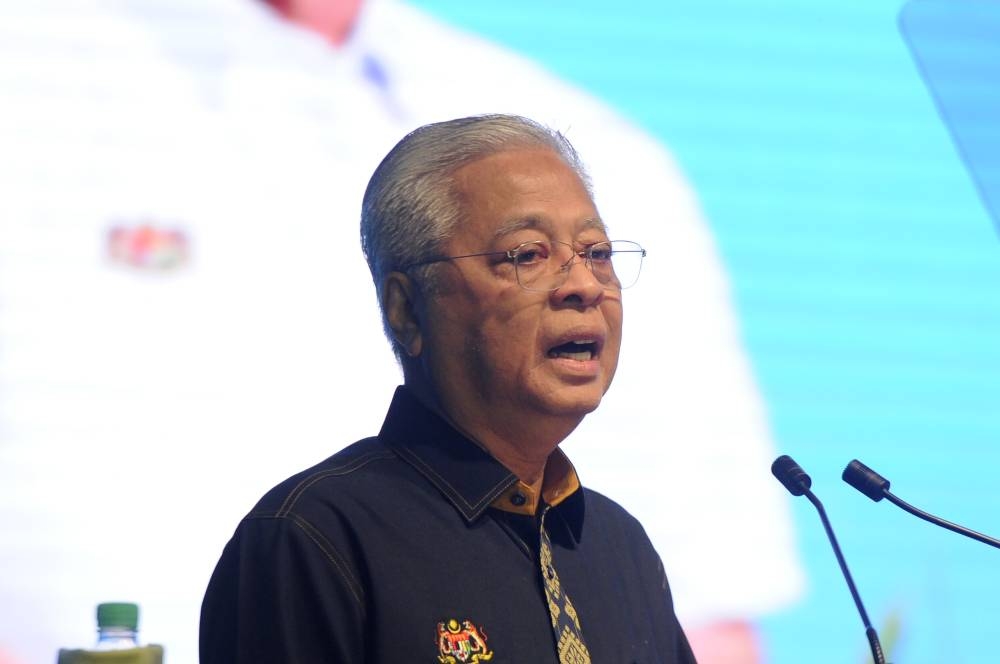

KUALA LUMPUR, Aug 21 — Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob said that the thought of becoming prime minister had never crossed his mind, nor had he any ambition to lead the government before being appointed to the role.

He called himself “a simple man” who only wishes to be remembered for serving the public to the best of his ability, and he had shouldered the responsibility even as the position was the result of what he called a unique political situation engulfing the country then.

“In my case, there was no planning, maybe the only planning in play was from Allah. Because of that, I never felt any pressure. They ask me if I can sleep at night with all the issues at hand, I say no problem,” he said in a recent interview with the Malaysian media.

“If after the next general election God wants me to continue as prime minister, it’s also not a problem for me. I only want to do the work.

“Responsibility was given to me, and I must deliver. At the very least, people will remember me as serving them,” he added.

Ismail Sabri was appointed prime minister after he was deemed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to be commanding the majority of the Dewan Rakyat, after his party Umno retracted its backing for his predecessor Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin.

Ismail Sabri explained that when he entered office a year ago, the two biggest challenges he faced were the political instability the country was mired in at the time, and the need to bring Malaysia’s economy back to life.

He explained that the two issues came hand in hand, and that for the economy to be stable, the country’s political scene had to be stabilised first.

“When I took over the government, the political scene was unstable because there were already two other prime ministers before me. Never in our history had there been three prime ministers in one [Parliamentary] term.

“It was very obvious that when the conference of rulers met and made a decision, the Agong wanted a stable government. That is why, for the first time in our history, on the second day I was in office, three Opposition leaders came into my office with me to sign the first MoU that would be signed again later,” he said.

Ismail Sabri was referring to the Memorandum of Understanding on Transformation and Political Stability signed between the federal government and Pakatan Harapan on September 13, that aimed for a political ceasefire amid rising political crises and the relentless Covid-19 pandemic.

He explained that it was initially difficult for his Umno party mates to come to terms with the MoU, attributing this to a political culture in Malaysia wherein the ruling party would never be caught working with the Opposition, and vice versa.

“So we needed to explain to the party, to help them understand why we signed the MoU. The challenge was to stabilise politics, and certain individuals found that hard to accept.

“So the level of acceptance from the people in my party in the early stages was quite difficult. Suddenly we are friends with the Opposition. Suddenly there’s an MoU with the opposition. So it was quite difficult,” he said.

Once that was settled, Ismail Sabri said the next challenge was to bring Malaysia’s economy from the brink of devastation, whose misery was further pushed when Russia launched an invasion of Ukraine, causing the global economy to crumble.

He said reopening every economic sector after shutting them down for two years was not an easy task, especially for small to medium enterprises, adding that many incentives were given out to help them recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a result of this, he said that according to Bank Negara Malaysia, Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP) is the best in South-east Asia, unemployment rates have gone back down to below pre-pandemic levels and Malaysia’s trade has surpassed the RM2 trillion mark — the highest ever recorded.

“So even though the world economy has not fully recovered, even though we have not fully recovered, we can see some results now,” he said.

“In terms of gross, we expect 5.3 per cent to 6.3 per cent, even if the International Monetary Fund predicts the rest of the world is about 3.2 per cent. We’re better than anywhere else, but there’s a lot more to do,” he said.