KUALA LUMPUR, June 25 — The World Bank has given an even gloomier outlook for Malaysia’s economic growth by predicting that the country’s GDP would contract by 3.1 per cent, compared to just about three months ago when it predicted negative growth of 0.1 per cent

In its Malaysia Economic Monitor report titled “Surviving the Storm” released today, the World Bank said the expected drop in economic growth in 2020 for Malaysia is mainly due to the “sharp slowdown in economic activity” in the first six months of the year.

The World Bank explained that Malaysia’s economic growth in the first three months this year (first quarter) had slowed to just 0.7 per cent following a series of movement control orders (MCO) to slow the spread of Covid-19 as well as economic activity severely constrained by deep uncertainty of growth prospects.

The World Bank also based this projection on its forecast of an output contraction of around 10 per cent in the months of April to June (second quarter) this year, matching the significant impact of economic disruptions arising from the MCO during these months.

“This is expected to be followed by a partial recovery in the second half of the year, as the outbreak eases and mobility restrictions are gradually lifted,” it noted in the report.

“This forecast assumes that the spread of pandemic is broadly contained at the global level and that the massive fiscal and monetary policy support measures implemented by governments around the world limit the depth of contraction in global economic activity. With all these factors, the near-term outlook for Malaysia’s economy is unusually uncertain at present,” it added.

In contrast to the World Bank’s forecast of -3.1 per cent for Malaysia in 2020, Malaysia had recorded positive economic growth at 4.7 per cent in 2018, and 4.3 per cent in 2019.

The Malaysian government has continuously imposed the MCO in various phases since March 18, with the latest phase — the recovery movement control order (RMCO) phase expected to last until August 31.

As for household spending and business investment spending which typically contribute to Malaysia’s economic growth, the World Bank said such spending are expected to increase gradually but remain subdued in the near future due to heightened uncertainty.

Among other things, it noted that many households and companies would be expected to increase their savings and to delay investment plans this year amid income losses from the MCO and uncertainty over future income and profits.

The World Bank forecasted private consumption to fall sharply from the 7.6 per cent in 2019 to 1.2 per cent this year, and for aggregate investment growth to fall from -2.1 per cent in 2019 to -4.9 per cent in 2020.

With global trade expected to take longer to recover, the World Bank predicted Malaysia’s exports and imports to shrink sharply by -12.9 per cent and -9.2 per cent this year.

The World Bank said the public health crisis due to the Covid-19 pandemic could affect Malaysia’s longer-term growth prospects as it moves to high-income country status within this decade.

“Beyond its short term impact, steep recessions triggered by the crisis could potentially have long-term consequences on growth through multiple channels, including long lasting changes in consumer spending patterns and persistently weak confidence accompanied by a buildup of savings, low investment and reduced aggregate demand and supply; the erosion of human capital associated with prolonged unemployment and widespread learning disruptions; and a retreat of global trade and supply linkages,” it said, before proceeding to outline measures that Malaysia could take in the short, medium and long-term in the same report.

Higher fiscal deficit with government spending surpassing revenue

The World Bank estimates that Malaysia’s fiscal deficit could widen to as much as seven per cent of the GDP for 2020, which it said would put the government in a very tight spot if the country needs more economic stimulus.

For its forecast of the fiscal deficit, the World Bank highlighted that this was due to projected increase in government spending by RM35 billion due to costs linked to the Prihatin and Penjana economic stimulus packages, as well as due to falling global oil prices that could lead to the already declining government revenues to drop further.

Noting that global oil prices are expected to fall to almost half the level assumed by the Malaysian government in 2019 when making Budget 2020, the World Bank’s own calculations suggested that the government could have a shortfall of at least RM22 billion from the earlier Budget 2020 estimate of RM245 billion in government revenue, mainly due to loss in petroleum-related income.

“In addition, the various tax exemptions granted in the Penjana plan also represent loss of potential revenue,” it said.

The World Bank further said that the Malaysian government could opt for several immediate options to prevent the budget deficit from going up too much this year, such as by exploring the selling of selected government assets or seeking for higher dividend payouts from government-linked companies such as state oil giant Petronas.

“The government could also explore other non-tax revenue measures through higher dividends from GLCs such as Petronas, as well as through the sale of selected government’s assets.”

“However, this reliance on GLCs may have negative implications for the GLCs financial standing,” it noted.

Another option would be for the Malaysian government to recalibrate or adjust the operating expenditure for selected items in its budget, although the savings from this may not be enough to offset the fall in revenue, the World Bank said.

But while such options can be carried out immediately, the World Bank pointed out that these measures may be insufficient to give the government enough financial breathing space to pump in more money for economic stimulus packages if the impact from MCO is greater than expected or if another round of MCO is required.

The World Bank then said the Malaysian government could consider making changes to existing laws through a special emergency Covid-19 Bill in Parliament, in order to free the government from current legal limits that would enable it to borrow to fund any necessary economic stimulus.

“An emergency bill which is expected to be tabled in Parliament in July 2020 would be an opportunity to address existing statutory limits, which would provide the government with greater flexibility to meet its financial needs during and immediately following the pandemic.

“The proposed measures include raising the statutory debt limit from the current 55 per cent of GDP and temporarily permitting the use of government borrowing to fund operating expenditures. This would allow debt to be used to facilitate the payment of cash subsidies and transfers and to meet the healthcare sector’s immediate operational needs, including boosting its Covid-19 testing capacity.

“The emergency bill could also cover the expansion of certain assistance programmes, including the Employment Insurance Scheme Act (2017),” it said.

The Malaysian government had in recent years sought to cut down its budget deficit although global oil price levels had hampered the efforts in latter years, and had last year projected a deficit of 3.2 per cent for this year.

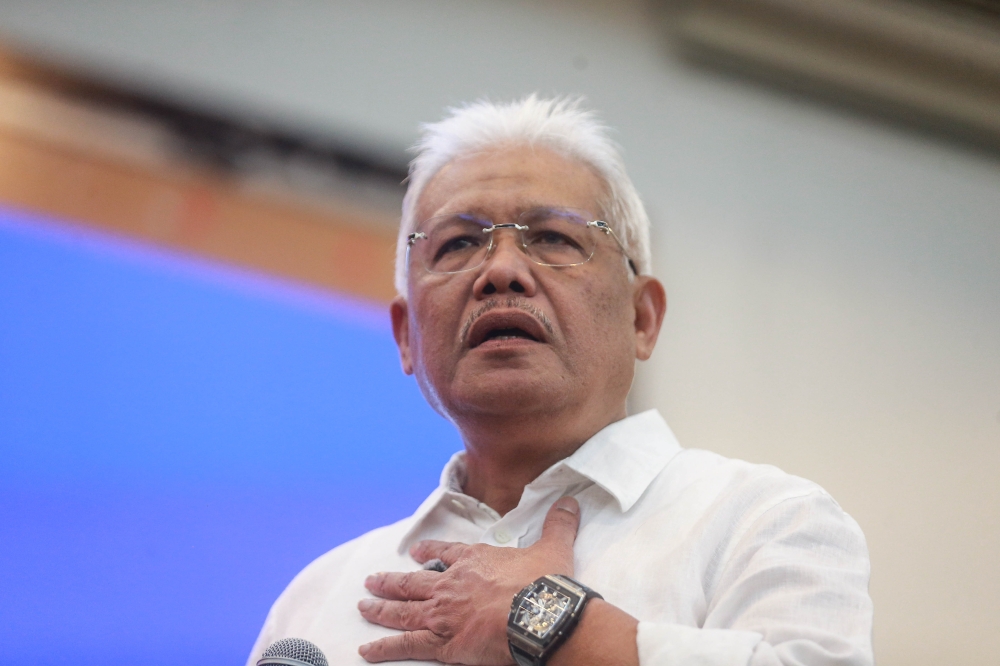

But unexpected spending brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic in the form of economic stimulus packages by the Malaysian government has caused the projection to go higher, with Malaysia’s finance minister predicting in late March that the fiscal deficit could go up to four per cent, before saying earlier this month that it could go up to six per cent this year.