JANUARY 13 — For much of the post–Cold War era, South-east Asian states operated on a comfortable axiom: sovereignty was secure so long as borders were respected and the region avoided the gravity of great power conflict. Hedging and non-alignment were the primary tools of the trade – practical, tactical mechanisms for navigating between giants, extracting concessions, and preserving a wide radius for manoeuvre. This was the era of the “Asean Way,” where the sanctity of the map was the ultimate guarantor of political survival.

In recent years, however, that axiom has begun to erode. Territorial politics has not vanished, but it has undergone a profound mutation. Modern states now rely on a deep, invisible stack of infrastructure – digital, logistical, financial, and technical – that they increasingly do not own, do not understand, and cannot replicate. Influence is migrating from the political realm to the operational one. Power no longer settles exclusively on the actor who claims the land, but on the actor who keeps the state functioning in moments of systemic stress. The map remains the same, but the “operating system” running on top of it is being outsourced.

Traditional intervention as a residual model

The 2024 removal of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela served as a stark reminder that traditional intervention remains a live option in the geopolitical toolkit. These “kinetic” operations – reminiscent of the US incursions into Panama in 1989 or Grenada in 1983 – are familiar to the analyst and the historian alike. They fit neatly into Westphalian frameworks of coercion, regime change, and the physical exercise of power. They are visible, loud, and conceptually legible; they are the “hard power” events that dominate news cycles and diplomatic protests.

But this traditional model is increasingly a trailing indicator. While the world watches for troop movements and naval blockades, a more consequential form of state influence is emerging in the shadows of the technological stack. This new mode of power is largely absent from public debate because it does not look like “power” in the classical sense – it looks like service provision, efficiency, and disaster relief.

Functional control: The Greenland blueprint

A pivotal moment in this shift occurred in 2026. The United States executed a strategy in Greenland that bypassed the clumsy, high-friction mechanisms of annexation or purchase. Instead of attempting to change the flag, a consortium of American contractors, logistics giants, satellite firms, and fintech companies assumed the “nervous system” of the territory. They began running the essential systems of daily life: high-speed communications, emergency response protocols, maritime navigation, energy microgrids, and financial rails.

While legal sovereignty remained in Copenhagen, functional sovereignty migrated toward the providers who ensured the territory remained viable. When a subsea cable failed or a microgrid required a firmware update, the solution did not come from the Danish state, but from the American provider. International law, grounded in 17th-century assumptions of “land and sea,” offers no vocabulary for this development. Westphalia treats sovereignty as a binary, territorial asset; in the digital age, sovereignty has become layered, divisible, and increasingly mobile.

This is the rise of the Provider State: a power that expands its frontier not by shifting borders, but by operating the essential infrastructure that underpins modern governance. It does not conquer territory; it provisions the systems without which sovereignty cannot be exercised.

Historical echoes and technical depth

This phenomenon is not entirely without precedent, though its modern depth is staggering. The British East India Company exercised fiscal, administrative, and military functions in India for a century before the Crown assumed formal rule in 1858. Similarly, the Treaty Ports in China and the Ottoman “capitulations” allowed foreign powers to manage customs, policing, and legal institutions without the burden of formal annexation. These were early experiments in hollowing out sovereignty from within.

However, the contemporary landscape is defined by a new technical depth of dependency. Today’s states depend on cloud compute, digital identity systems, undersea cables, and pharmaceutical supply chains that require specialised expertise and carry prohibitive “exit costs.” Unlike the customs houses of the 19th century, a modern cloud-based tax system or a national digital ID cannot be nationalised overnight with a simple decree. The technical complexity creates a “lock-in” effect. The actor who operates these systems gains the leverage that geography – mountains, oceans, and fortresses – once provided.

Provisioning as the new alignment

The emerging global competition is not primarily ideological. States are not choosing between “isms” or competing visions of the social contract; they are selecting providers capable of maintaining essential functions. In an era of polycrisis, alignment follows competence.

The United States dominates the “high-end” stack: cloud infrastructure (AWS/Azure), satellite constellations (Starlink), and advanced pharmaceutical logistics.

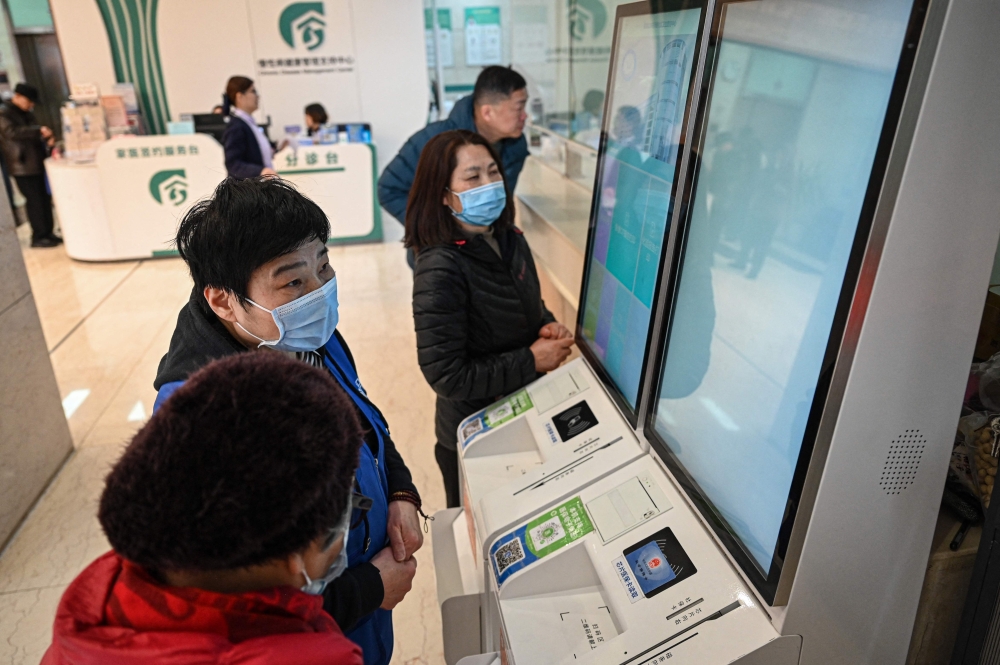

China exports the “hard” digital and physical rails: 5G networks, port management systems, hydropower, and industrial hardware.

Japan and the Gulf States deploy niche but vital layers: high-trust financing, disaster-resilient engineering, and energy security networks.

India is increasingly exporting “Digital Public Goods” – modular software for payments and identity that offer an alternative to Western or Chinese stacks.

This is not a bipolar contest in the Cold War sense, but a competitive provisioning environment. Influence is accumulated by making oneself indispensable to a neighbour’s survival. If you run a nation’s payment gateway, you do not need to threaten them with sanctions; the threat is inherent in the operational dependence.

South-east Asia: The architecture of survival

This dynamic is most acute in South-east Asia, a region that sits at the centre of the world’s most critical maritime corridors. One-third of global seaborne trade passes through the Strait of Malacca. The regional economies depend on a high-velocity rhythm of maritime logistics, aviation, and semiconductor throughput that cannot tolerate a single heartbeat of disruption.

Furthermore, the region is uniquely exposed to climate and geological volatility. In South-east Asia, disaster is a mechanism for external provisioning. When a mega-typhoon or volcanic eruption overwhelms local capacity, the first actor capable of restoring a power grid, a communication network, or a payment system sets the strategic terms for the recovery. Provisioning in a crisis is the ultimate “soft power” that hardens into “structural power.”

This “operational surrender” is already underway. Across much of Asean, cloud services, cybersecurity, and e-commerce logistics are already foreign-operated. Undersea cable landing points are controlled by multinational consortia. Even the “protected” domain of financial payments is being externalised to global platforms. The region is becoming a patchwork of foreign-operated systems, leaving the state as little more than a legal shell.

The end of manoeuvre

The strategic risk for South-east Asian leaders is not that they will be forced to “choose sides” in a neo-Cold War between Washington and Beijing. The more immediate risk is that they will lose the structural capacity to avoid choosing.

Hedging presupposes redundancy. To hedge, a state must have the ability to switch providers or rely on domestic backups. But as functions are deeper embedded into foreign-operated stacks, redundancy disappears. If a state’s cloud infrastructure, port logistics, and vaccine supply chains are operated by a single external power, “non-alignment” becomes a purely declaratory gesture.

A state that cannot reboot its own systems after a shock is no longer a player in the geopolitical game; it is a client. The alignment is no longer a political choice made by a prime minister in a palace; it is embedded in the architecture of survival. Neutrality, in this context, becomes an artifact of the past – a luxury for states that still own their own tools.

Possible outcomes for the decade

By the end of the 2020s, the region could face several distinct outcomes. In the most favourable scenario, provisioning remains distributed across multiple providers (a mix of US, Chinese, Japanese, and European firms), allowing Asean states to play them off against each other and preserve a semblance of autonomy.

In a less favourable scenario, provisioning consolidates into two competing ecosystems, forcing an alignment not through ideology, but through “operating systems.” You are either an “iOS State” or an “Android State,” with no interoperability between the two. The most destabilising scenario involves provisioning vacuums created by massive climate shocks, where external actors intervene ad hoc to stabilise fundamental systems, effectively ending local governance in all but name.

A new geography of power

Territorial politics are returning, but not in the form that international relations theory predicts. The Provider State does not need to annex land or install puppet regimes to secure compliance; it secures it through indispensability. It acquires dependency rather than territory. It influences without occupation.

For South-east Asia, the fundamental strategic question is no longer “Who owns this island?” but “Who runs the systems that allow this society to function?” The answer to that question will determine whether Asean’s long-standing commitment to autonomy remains a living reality, or whether it becomes a historical footnote in a world where sovereignty was assumed rather than provisioned. In the new geography of power, the flag follows the provider.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.