KUALA LUMPUR, June 22 — Malaysia still has a “long way to go” in effectively using its resources to help its residents enjoy rights linked to quality of life, particularly in ensuring the rights to education and food, the latest results from an international human rights tracker showed.

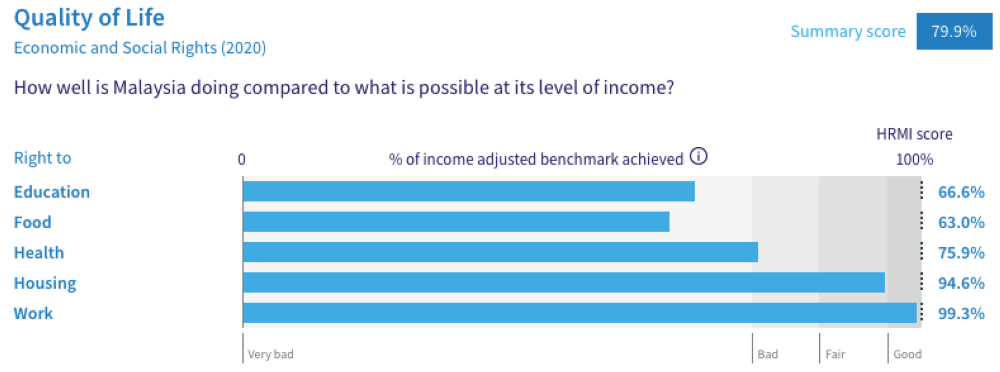

In the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s (HRMI) Rights Tracker 2023, Malaysia scored 79.9 per cent for the “Quality of Life” section or only 20.1 per cent less than what it is capable of at its income level as of 2020.

“This score tells us that Malaysia is only doing 79.9 per cent of what should be possible right now with the resources it has.

“Since anything less than 100 per cent indicates that a country is not meeting its current duty under international human rights law, our assessment is that Malaysia has a long way to go to meet its immediate economic and social rights duty,” the HRMI said on its Rights Tracker website.

According to HRMI, every country could achieve 100 per cent based on its income level if they use their available resources effectively, and that any score lower than 100 per cent means that improvement is needed while also showing that a country has the potential to do better.

Where does 79.9 per cent put Malaysia at? It is now in the “bad” category, where it failed to have the kinds of structures and policies enabling the claiming of rights for quality of life.

The HRMI has four categories for its Quality of Life scores, namely “good” (95 to 100 per cent), “fair” (85 to 94.9 per cent), “bad” (75 to 84.9 per cent), and “very bad” (below 75 per cent) where countries have not only failed to have structures and policies to help people claim their rights but existing structures and policies most likely prevent many from claiming their rights.

In the Rights Tracker, Thailand’s Quality of Life overall score is the highest in the South-east Asian region at 88.2 per cent (“fair” or doing an okay, but not good enough job of having structures and policies that enable the enjoying of rights), followed by Malaysia at 79.9 per cent (“bad”), Myanmar (79.2 per cent and in the “bad” category), the Philippines (74.7 per cent, “bad”), Indonesia (71.4 per cent, “very bad”), and Laos (69.1 per cent, “very bad”).

No overall score for Quality of Life rights was available for the other South-east Asian countries of Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore and Brunei due to incomplete data.

“Compared with the other countries in East Asia, Malaysia is performing close to average on Quality of Life rights,” HMRI said in its tracker. Those in the East Asia category in the Rights Tracker 2023 with overall Quality of Life scores are Japan (90.7 per cent), Mongolia (77 per cent) and Timor-Leste (65.4 per cent).

How did Malaysia get those scores?

For the Quality of Life section, five economic and social rights are covered, with Malaysia’s HRMI scores as of 2020 being “very bad” for the right to education (66.6 per cent) and right to food (63 per cent); while being “bad” for right to health (75.9 per cent) and “fair” for right to housing (94.6 per cent) and good for right to work (99.3 per cent).

Being grouped as a low- to middle-income country (unlike high-income countries like Singapore and Japan, which may use other indicators), Malaysia’s 66.6 per cent right to education score was based on 2020 statistics such as having a 98.4 per cent enrolment rate in primary schools and having only a 60.5 per cent upper secondary school enrolment rate, which translates to HMRI scores of 93.8 and 47.2 per cent for these two components. The last component of quality education had a 58.9 per cent score.

Malaysia had a 94.7 per cent and 93 per cent HRMI score for both female and male in terms of primary school enrolment rate; but this fell to 50.5 per cent (female) and 44.2 per cent (male) for secondary school, and was at 61.5 per cent (female) and 56.1 per cent (male) for quality education.

As for Malaysia’s right to food score of 63 per cent, it is based on 2019 figures of 78.2 per cent children under the age of five not being stunted and with this figure then used to calculate the score of the right to sufficient healthy food at 63 per cent. Using 2019 figures, 65.8 per cent male had sufficient healthy food, relatively higher than 60 per cent for females.

For Malaysia’s right to health score of 75.9 per cent, it is based on statistics such as 99.1 per cent of children surviving up to age five (as of 2020), 89.1 per cent survival rate for adults aged 15 to 60 (as of 2020), 34.3 per cent usage rate of modern contraceptives (as of 2014), which translates to these components’ HRMI scores of 96.9 per cent, 89.3 per cent and 41.6 per cent respectively.

Malaysia’s 94.6 per cent score for right to housing was measured based on 93.8 per cent and 99.6 per cent having access to water on premises (as of 2020) and having access to at least basic sanitation (as of 2018), which translates to these components’ scores of 90.3 per cent and 99 per cent.

Malaysia’s right to work score of 99.3 per cent was based on 99.6 per cent of people being “not absolutely poor” as of 2015, which translates to the score of 99.3 per cent when it comes to subsistence income.

The Rights Tracker’s 2023 data set was launched today and can be found at rightstracker.org, with yearly data available for five economic and social rights for 196 countries from 2007 to 2012 (depending on the right covered).