KUALA LUMPUR, Dec 27 — Malaysia has long tried to control the spread of dengue, but dealing with the pesky mosquitoes that transmit the disease through their bite is no easy task.

Despite deploying Wolbachia mosquitoes to "fight fire with fire" and fogging up entire neighborhoods with insecticide, dengue cases in Malaysia still managed to exceed 62,060 reported cases as of December – far more than the 26,365 cases it reported throughout 2021.

With climate change expected to alter the global footprint of many infectious diseases, experts say the dengue outbreak in Malaysia will only be made worse.

In fact, the World Health Organization even stated that dengue cases have increased by eightfold over the last two decades. Dengue is now considered endemic – consistently present – in more than 100 countries.

Currently, Malaysia’s main strategy to eradicate infected mosquitoes is through fogging. But if the solutions do not include adapting to the climate emergency, these efforts may be outdated and ultimately futile.

How does climate change increase the risk of dengue?

Apart from the well-known effects of climate change such as fluctuating weather conditions and global warming, a lesser-known effect is how it can significantly cause an upward trajectory of vector-borne diseases. But how?

“Higher temperatures shorten the time it takes for mosquito larvae to mature and the time taken for female mosquitoes to mature.

“This means that the female mosquitoes will be able to transmit these infections for a longer time,” Dr Neelika Malavige, the head of the Dengue Global Programme at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), said.

Mosquito eggs remain viable for several months in dry conditions and hatch only after coming into contact with water.

With the monsoon season, changing temperatures and prolonged weather spells could create new habitats for mosquitoes to breed.

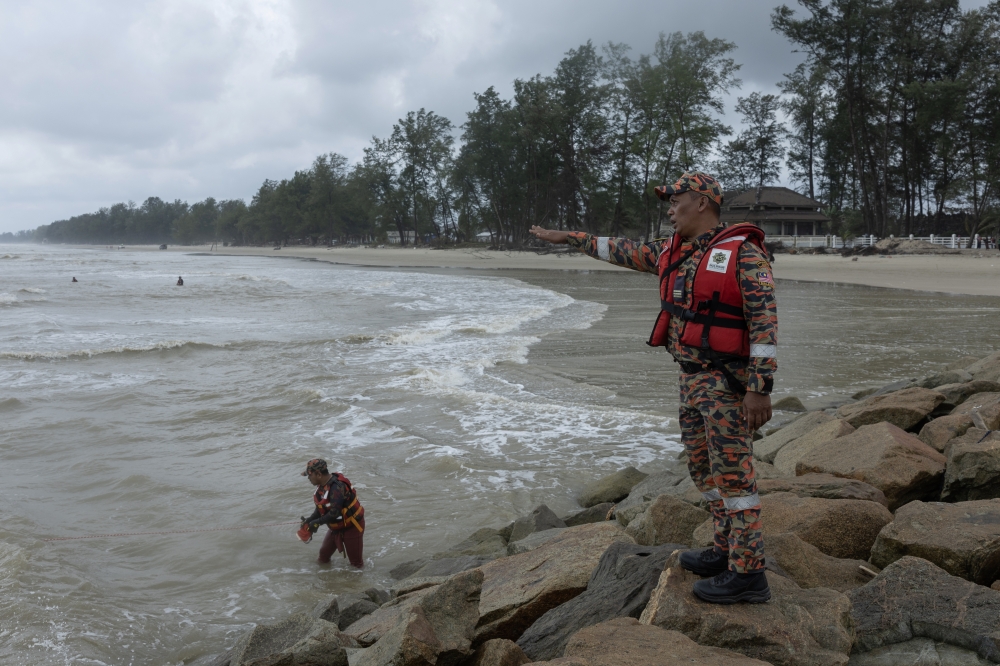

“During flooding or rainy season, dengue cases would usually decline as the torrential rainwater sweeps off all the mosquito eggs.

“Post flood, however, the dengue cases usually increase due to the suitable environment for the Aedes female to lay their eggs in the water that remains in the aftermath of the floods,” public health specialist Dr Rozita Hod said.

“Differences in temperatures of seawater cause salinisation of freshwater and groundwater in coastal areas, resulting in the vectors adapting to breeding in brackish water. These adaptations would further lead to difficulties in controlling the vector,” the scientist said.

Dengue prevention strategies must evolve

Distinguishable by its narrow, thin body with unique black and white markings on its legs, the Aedes mosquito is one of the world’s deadliest creatures.

An indication that someone in the neighborhood has contracted dengue is none other than large clouds of fine insecticide fogging up the area – killing all the wildlife in the vicinity, mosquito or not.

Impressive as it may seem, fogging is rarely an effective method of eliminating mosquitoes.

“Fogging kills the adult Aedes mosquitoes but does not deter the eggs from hatching into larvae. To kill Aedes, one must kill the adults as well as the eggs, the nymphs and larvae,” she said, adding that fogging works best with the combination of larvicide in common breeding areas.

There’s also evidence that rampant fogging can create mosquitoes with "superpowers" that are resistant to fogging.

For Dr Rozita, grassroots solutions might be one of the keys to significant reductions in dengue cases.

“We should empower the community with knowledge and skills to adapt to the changing environment and climate.

“For example, in areas where water supply is reduced and they have to collect water in containers, the community must cover these water-holding vessels to keep Aedes from laying their eggs in clear water,” she said.

Instead of waiting for local authorities to step in, the community could check if basic hygiene and sanitary conditions are met, including the proper management of solid waste.

But that’s not to say that it is entirely dependent on the community on the ground.

“I believe there has to be a serious commitment from the countries that are the topmost carbon dioxide emitters to cut down on emissions,” Dr Malavige said.

“Reduction in rising temperatures would be the key. There is a lot of discussion but never follow-up activities of these plans.

“I think it's important to learn lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic and understand that in order to fight infection and reduce the burden, we need to have many different approaches.

“This is why it is very important to urgently develop or discover safe and effective drugs that would prevent or limit progression to severe disease in dengue,” Dr Malavige said, adding that Indonesia recently registered a new dengue vaccine known as TAK-003 and other countries may soon follow suit.

Some more vulnerable than others

The infected experiences flu-like symptoms such as high fever, severe body aches, muscle and joint pains, and even a bad rash. In more extreme cases, internal bleeding, organ failure, and death.

In the past, children were predominantly the chosen victims of the Aedes mosquitoes. But over time, the median age of infections in South-east Asia has risen to the range of 15 to 45, affecting the population who is of childbearing age.

This would lead to more complications for the expecting.

“Dengue during pregnancy is associated with increased likelihood of severe disease and pregnancy-related complications and adverse fetal outcomes such as pre-term delivery, stillbirths, and miscarriages,” Dr Malavige said.

There has also been an increase in infections in the elderly – which adds to the vulnerable group’s already existing comorbidities.

No specific treatment for dengue fever exists. The usual protocol for someone with dengue is drinking plenty of fluids and getting enough rest.

Moreover, there are currently no reliable biomarkers to tell who will develop severe dengue. Because of that, all dengue patients have to be closely monitored so that timely action can be taken through fluid therapy if needed.

“However, due to the limited healthcare resources in many of the dengue-endemic countries, this is a huge burden for the healthcare facilities which have limited staff. There is also a huge economic cost incurred due to dengue every year,” Dr Malavige said.

A hopeful situation

As climate change worsens, diseases like dengue are likely to spread more quickly.

What’s good to note is that experts are confident of Malaysia’s potential to prepare for future outbreaks.

“Malaysia has taken a leading role in scientific research in the region. A good example is a work carried out on the development of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection.

“There is no doubt that Malaysia has the potential and can take a leading role in drug development for dengue and also initiate other dengue control measures such as a novel method for vector control,” Dr Malavige, the dengue expert said.

“Climate change would indeed lead to a further increase in the current burden of dengue.

“But it is something we need to address now.”

*This story was produced with the support of Internews' Earth Journalism Network and Climate Tracker.