KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 10 — Journalist Nor Arlene Tan is no stranger to getting “doxed”. In 2011, she was falsely accused by online trolls from hacktivist group GaySec of being the person behind controversial online persona Sitt Al Wuzara.

The trolls posted her voter constituency data, articles she wrote, photos, university profile, mobile number, and home address — all compiled into a PowerPoint presentation hosted online.

They also tried to gain access to her Google account, prompting her to activate the two-step authentication.

“I received backlash from people on the internet, as well as countless death threats. Also the culprit was never caught by the police or MCMC,” she told Malay Mail, referring to the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission.

“In my opinion, the rule of law was absent — and such online vigilantes still persist until today,” Arlene added.

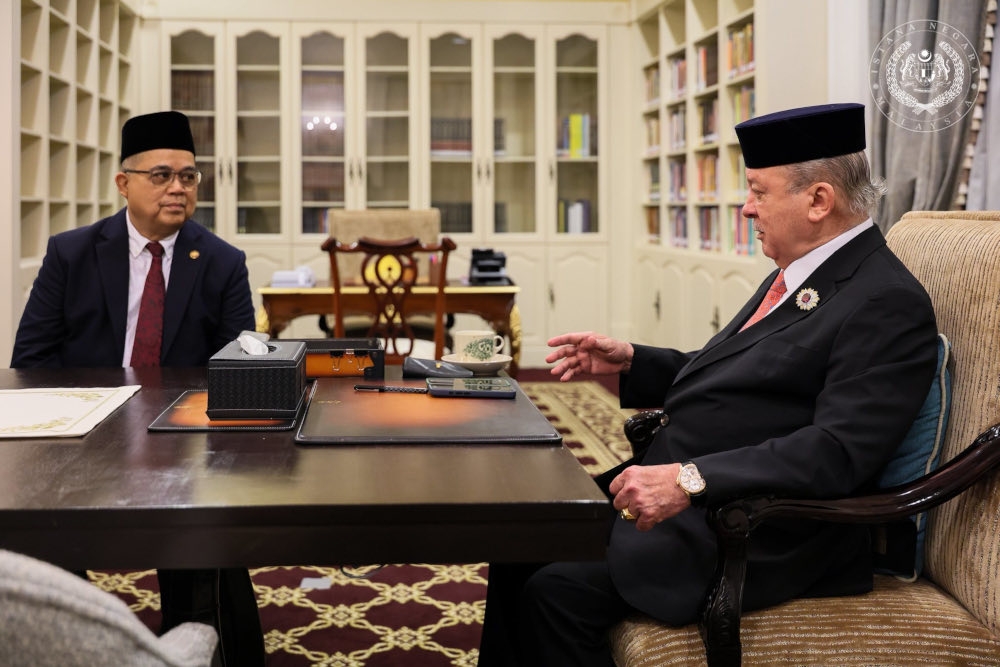

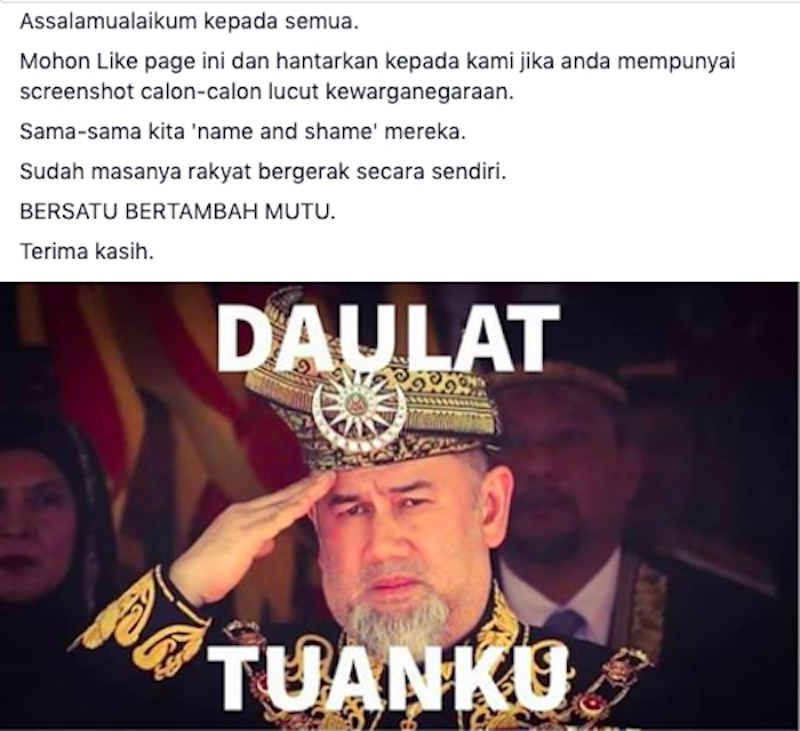

Following the resignation of Sultan Muhammad V as the Yang di-Pertuan Agong earlier this week, a group of online vigilantes took it upon itself to defend the honour of the Malay rulers by going after critics of the monarchy.

A Facebook page that has been liked by 13,670 users (at the time of writing) has so far listed eight targets, doxing them and calling for their employers to fire them.

At least four from the list have been sacked, suspended or resigned from their jobs, while three are now being investigated by the police for alleged sedition.

Doxing or doxxing, a term originating from the word “documents”, includes harvesting private information from publicly available data online or social media, and broadcasting such information, usually to identify someone.

In 2014, internet users doxed a woman shown abusing an elderly man in a road rage incident in Kuantan captured on video, identifying her from her car’s registration number.

They had also managed to ferret out her telephone number and her workplace information, publishing these online for all to see.

“It’s a very harmful and dangerous form of cyberbullying in my opinion,” Khairil Yusof, the co-ordinator of technology activist group Sinar Project, told Malay Mail.

But can victims seek recourse?

Lawyers polled by Malay Mail conceded that doxing on its own is not a criminal offence, although it could fall under Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 that handles improper use of network facilities or network service.

However, lawyer Foong Cheng Leong said this is only true if there had been publication of a comment which is obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass another person.

“Invasion of privacy is also possible but the information leaked must be something of a private nature — not those in the public domain like full name, identification card number and address.

“Tort of harassment is also possible but that must be something of a repeated act of harassment by the same person,” said the chairman of the Kuala Lumpur Bar Information Technology and Publication Committee.

Civil liberties lawyer Syahredzan Johan agreed, saying that unfortunately there is no legal provision that caters specifically to such acts.

“It is an offence, for example, for someone to have come across personal data which is processed according to the Personal Data Protection Act and then reveals that data to the public, but it does not cover instances where the information is obtained through public searches,” Syahredzan said.

Foong added that some online comments may be considered criminal defamation, while tracking one’s home address and taking photographs of one’s home may even be considered a form of harassment.

Criminal defamation is covered under Section 499 in the Penal Code, while Section 509 tackles word and gesture insulting the modesty of any person.

Syahredzan, who is also DAP MP Lim Kit Siang’s political secretary, and Subang DAP Socialist Youth chief Farhan Haziq Mohamed had yesterday condemned the arrests of the three individuals, calling it a breach on the moratorium of the Sedition Act.

In a joint press statement, the duo pointed out that the Cabinet resolution to lift the moratorium on certain acts including the Sedition Act was limited to exceptional cases involving national security, public order and race relations.

Last month, Malay Mail had reported that in Malaysia, local employment laws allow for employers to dismiss their employees for something said online, even without a notice period.

Lawyers said this move can be taken if the staff is considered to have committed serious misconduct, and subsequently hurt the company’s image.

This is Part Two of a two-part story. If you have not read Part One, “A rise in pro-monarchy vigilantism follows Agong’s resignation”, please click here.