KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 10 — The issue of child marriage has cropped up over the years but without much resolution.

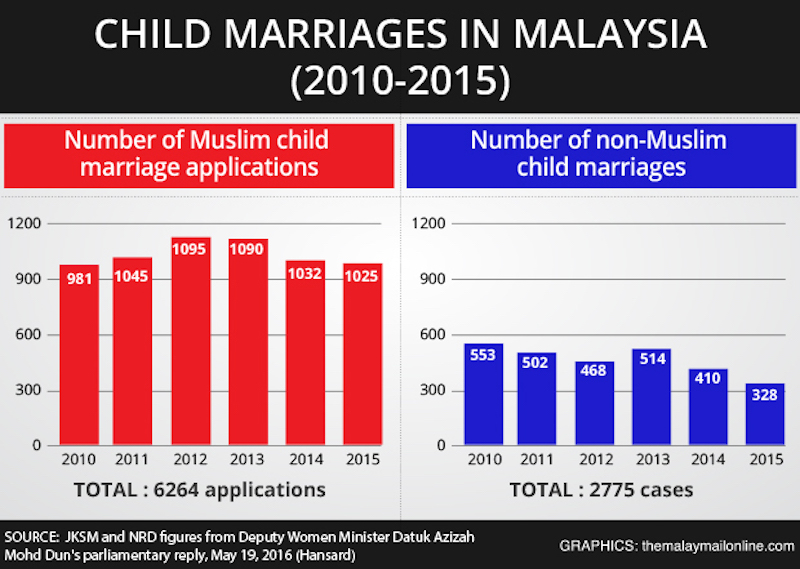

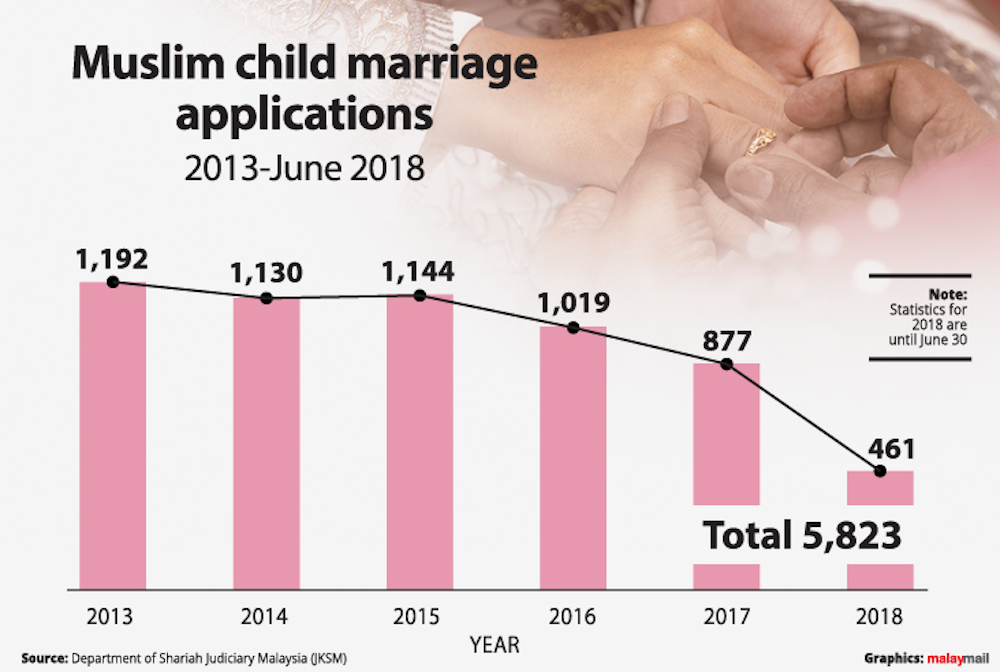

While data is scant, Deputy Women, Family, and Community Development Minister Hannah Yeoh in late July announced 14,999 child marriages were recorded between 2007 and 2017, 10,000 were Muslims.

Statistics also pointed to Sarawak having the highest number of registered child marriages.

Meanwhile, the Child Rights Coalition Malaysia reported that records in 2009 showed that 32 children under the age of 10, 447 children between 10 and 14, and 8,726 children in the 15-19 age group underwent pre-marital HIV tests.

That is a total of 9,205 children who might have entered into marriage.

The coalition’s data also showed 900 child marriages were approved in 2011 and 1,022 in 2013.

All that came to a head when in July a 41-year-old man from Gua Musang married an 11-year-old girl in Thailand.

In September, a 44-year-old man in Tumpat took a 15-year-old girl as his second wife with the approval from the Shariah Court.

Both cases ignited strong public interest, which led to Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad on Oct 20, issuing an order to all state governments to raise the minimum legal age for marriage to 18 years for Muslims and non-Muslims.

In the eyes of the law

In the eyes of the law

The Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 puts the minimum age for marriage at 18 but girls can marry at 16 after obtaining a licence from their state’s chief minister.

Those under 16 are not allowed to get married. In addition, the law makes it compulsory for either party who have not reached the age of 21 to seek permission to marry from their parents.

Meanwhile, the Islamic Family Law sets a minimum age of 18 for boys and 16 for girls. But those under the legal age can seek permission to marry from the Shariah Court.

Senior civil and Shariah lawyer Nizam Bashir said although Islamic law is a state matter, it is not to say that the prime minister has no influence.

“Jakim, which is a department under the prime minister’s purview, functions as a federal coordinating body vis-à-vis state Islamic agencies. Through Jakim, the prime minister is able to direct how the law develops on this issue.

“Nevertheless, the laws can only be changed either at an executive level through changes in administrative processes; or at a legislative level, through laws passed by the state legislative assemblies or Parliament,” he said.

He also said provisions that allowed for child marriages to be approved by chief ministers and Shariah Court judges are ripe for reform.

Under the existing laws, there is no clear outline of what constitutes the criteria for approval or rejection when it comes to child marriages.

“In my experience, when things are that ‘mysterious’, by and large, that is where abuse can happen. Consequently, all stakeholders should aim to prevent ‘mysticism’ and to promote transparency and objectivity where the law is concerned,” said Nizam.

“Generally, a welfare report ought to be procured and a Shariah judge should consider the report as well as evidence from relevant parties before determining whether it is in the best interest of the child for the marriage to take place.”

Child marriage norms

Child marriage norms

Unicef’s stand on child marriage is clear — legal minimum age of marriage is at 18, without exception. This is in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child that Malaysia has ratified.

Unicef senior child protection specialist Sarah Norton-Staal said she felt encouraged by the prime minister’s statement on raising the legal minimum age for marriage to 18.

“Although Pakatan Harapan had promised in its election manifesto to raise the minimum legal age for marriage to 18, instructions coming from the highest level of authority gives weight to this issue.

“While the issue of child marriage doesn’t impact a large number of children, it is still cause for concern, especially after the two high-profile cases came to light this year.”

However, she pointed that those cases were the outliers and most child marriages are between consenting teenagers.

In a local study by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia researchers that Unicef supported, 140 boys and girls involved in child marriage were interviewed and analyses of Shariah Court files.

It found the factors that place children at risk were low household income (correlated with children dropping out of school), poor understanding of sexual and reproductive health issues (led to a higher risk of pregnancy out of wedlock), parents lack an effective intervention support system, and community acceptance of child marriage.

“Majority of child marriages were results of premarital sex, teen pregnancy or facing high risk of pregnancy. Their parents felt it was important to get married, at least to give legitimacy to the children that would be born.

“Social norms accept child marriage is best solution when teens become sexually active or become pregnant, not just in traditional communities, but the issue cuts across rural, urban, ethnic and religious lines,” said Norton-Staal, adding that child marriages violate children’s rights to education, economic opportunities and good health.

Young mothers are faced with maternal mortality and low birth rate, while boys will have diminished potential and in many cases, unable to support his young family, so parent and communities need to be aware of these problems, she said.

The study also mentioned the lack of reproductive health information among teenagers.

“Taboo on reproductive health education is still evident. The subject is only allocated a very minimal 12 hours a year. The students are not tested on it and teachers are reluctant and uncomfortable to get into it.

“The way it might be presented is not helpful or informative, and even adds to confusion among the students,” she said.

She added that pregnant students are not allowed to be in school and the Education Ministry admitted no one takes note of why they drop out of school.

Norton-Staal and her team had field visits to Sabah to speak to communities and native court judges, and found that there was a lack of understanding and awareness on the risks of child marriages.

“However, it is encouraging that the communities and judges are open to learning and wanting to hear more about what we have to share.”

Ripe for reform

Ripe for reform

The UKM study found there is there is no standard operating procedure to guide Shariah Court judges through the child marriage application process as they often rule from the position that child marriage is a viable solution to premarital sexual activity and pregnancy out of wedlock.

According to case files and judges’ notes made available to researchers, reasons that Shariah Court judges gave for approving child marriage applications included the children’s ability to support a family and manage a household, their memorisation of basic Islamic teachings and the availability of family support after marriage.

While reasons for rejecting marriage applications included any evidence of coercion, lack of consent from a guardian, a lack of knowledge of basic Islamic teachings, unemployment (for male applicants) and a criminal record.

After an analysis of case files (2012 to 2016) from the Shariah Courts of seven states, the study reported that of 2,143 applications for child marriage, only 10 were rejected.

Lawyer and Voice for Children Sharmila Sekaran said there is a public misconception that child marriage is a Muslim issue while statistics have shown it to be a Malaysian one.

“The misconception comes about because Muslim girls below 16 years old can have a pathway to marriage via the Shariah Court while the law for non-Muslims explicitly says girls below age of 16 cannot enter into marriage,” she said.

“Shariah Court judges are to use their judgment when deciding on child marriage cases. However, the process doesn’t take into consideration that marriage is not the best means to protect a child.

“This is symptomatic of how society has viewed child marriage. Some people have voiced support for child marriage, alluding to it is in the child’s best interest.”

Child’s best interest

Child’s best interest

Sharmila also said for much of human existence, child marriage was practised by European royalty, in many Asian cultures, Latin America and so on.

Though her NGO work, Sharmila has observed those in child marriages are often inadequate and inept when it comes to parenting as they are still children themselves.

“These young parents are not equipped to guide their children on how to live in an industrialised nation as they need far more skills to provide for themselves.

“Hence, the next generation is caught in a poverty cycle. I also noticed that many child marriages invariably break down for many reasons.

“Today, we have scientific proof that a girl’s physiology often does not allow her to carry a child to full term until she is above a certain age threshold. Just because a child is able to become pregnant, it does not mean it is in her best interest to do so.”

Sharmila said to eliminate child marriage, the laws have to be in place and then get the of society on board.

“If you want to be a productive nation, the women and children need to be educated, not be married off young. Boys have supported the cause as well because they are also victims.

“You can introduce a moratorium first so people who are already in child marriage are not prosecuted. Of course, it is a process that can take years. But at least the children that come after will not be subjected to child marriages.”

Now that the law will be changed in Malaysia, she said it confirms the aspirations of what Malaysians want for their country as well as support for advocacy work on the ground.