COMMENTARY, Jan 30 — There is an unfortunate tendency for many of us to tune out our better halves after a certain number of years together. Sometimes it takes decades, sometimes a marriage is all that is required. We are only human.

Yet I find that my ears perk up when my beloved tells me about some new video pertaining to Cantonese cuisine.

(It’s a joke in my family that everyone who marries into our Cantonese clan ends up being more Cantonese than the "originals” themselves. A joke, but not inaccurate...)

On whether we ought to judge a dim sum parlour by its har gow (prawn dumplings) or its wu gok or crispy taro puffs. Or how the entire point of ordering a glistening lor mai gai is to tentatively dig in and discover its treasures of mushroom, chicken, Chinese sausage and more.

I nod, barely absorbing half of the stream of information. Why do I need to know all — or any — of this?

Surely one can appreciate the dishes of one’s heritage without obtaining an encyclopedic knowledge of the ins and outs of the cuisine itself? Aren’t functional taste buds enough?

Perhaps. But there is so much more one can glean from listening to one’s spouse.

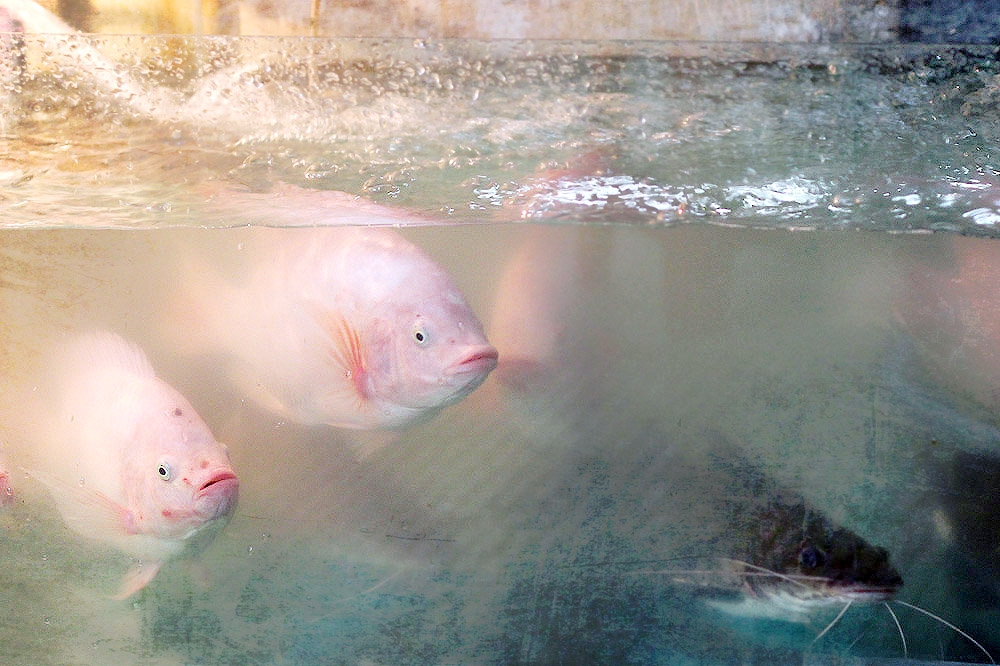

For many of us, Cantonese cuisine is nothing more than dim sum and steamed fish, the former to be savoured as weekend brunch in dim sum restaurants and the latter to be prepared at home, if one wakes up early enough to get to the pasar for the freshest catch of the day.

It’s not an unfair assumption. Take steamed fish or zing yu, for instance. I have inherited, either by nature or nurture, my father’s militant approach to what constitutes a proper Cantonese steamed fish.

Fish has to be fresh. Sea caught is better than freshwater. Wild is better than farmed. Fish must never be steamed a second more than necessary, and never too high a temperature. If the fish is fresh enough, all we need are scallions, not a bushel of ginger to mask any fishy stench.

And so on.

(Given such rigorous requirements and kitchen mastery, it’s a wonder any of us Cantonese find a match outside of our clan...)

Social media can be a bane on the best of days, but sometimes they provide some respite and amusement. There’s one particularly astute clip where a hapless staff at an office offers to order lunch delivery for the team.

Naturally there is one Cantonese colleague who finds fault with every single suggestion. My favourite is when he reviews the entire menu and grouses:

"Mou ceng choy wor...” ("No green vegetables though...”)

And that made me laugh out loud, for I have been guilty of the same complaint many a time when dining out with friends. It’s not really a proper meal without some clear soup, a good protein... and some leafy greens.

No salads, please. Vegetables ought to be cooked, not raw. And it’s not green when the poor leaves have been boiled or stewed into a brown, unrecognisable sludge. A quick blanch or stir fry is all they need.

When you fiddle and fuss so little with the fresh greens, from their delicious leaves to their crunchy stalks, all you need is a generous drizzle of light soy sauce or oyster sauce.

Less is more in Cantonese cuisine.

The simplest flavours, the best ingredients, the years of cooking passed down from generation to generation, master to student. When it’s this good, you don’t need much adornment.

Start the morning with some slippery smooth chee cheong fun (rice noodle rolls) or a bowl of pei dan sau yuk zuk or congee with century egg and lean pork.

Lunchtime calls for some siu mei (roast meats), from the ubiquitous cha siu (barbecued pork) to harder-to-find siu ngo (roast goose).

Dinner could be steamed rice with some glazed gu lou yoke (sweet and sour pork) or a flash fried plate of gon cau ngau hor (dry beef noodles), redolent of smoky wok hei.

Which brings me back to the matter of our loved ones, our partners in crime, our — clichéd as it might sound — much better halves.

Sometimes it can appear that we are tuning out, missing most whatever they are saying. Yet in my experience, this isn’t really true. We are listening but we are comfortable enough not to need to respond to everything.

Less is more. Sometimes all we need is to snuggle up and watch a funny clip together.

It’s more than enough. A good relationship is like Cantonese cooking: it takes years of practice and a sensible amount of restraint.

We don’t need much more; we are only human.

*Follow us on Instagram @eatdrinkmm for more food gems.