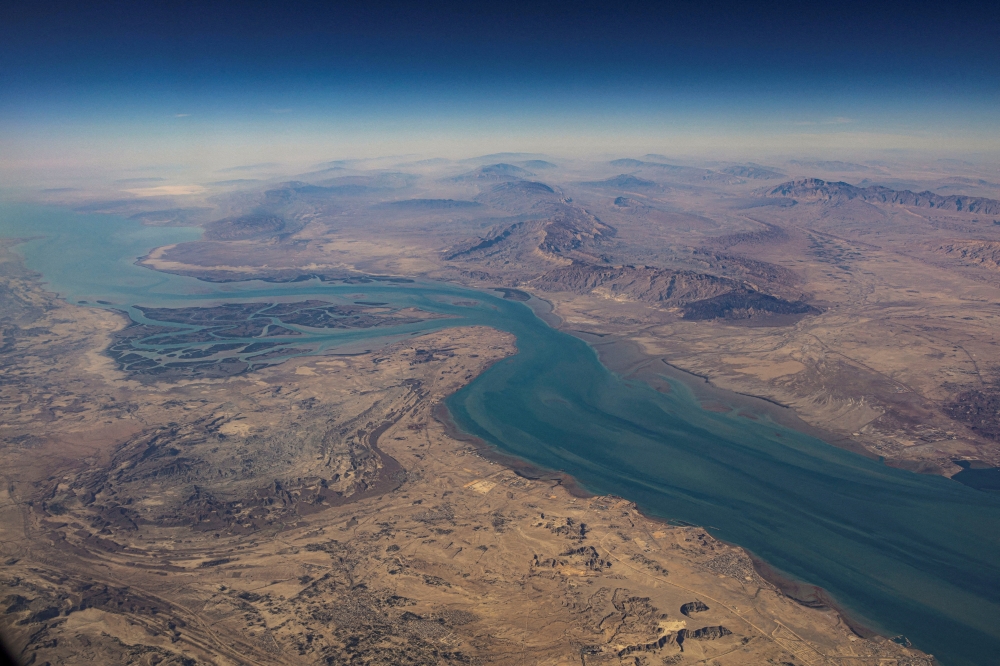

JULY 27 — Indonesia has recently issued its new map in 2017 asserting its sovereignty and sovereign rights over a number of maritime areas in, among others, the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, the South China Sea and the Celebes Sea.

As a country that shares the Straits of Malacca and Singapore with Indonesia, it is therefore crucial for Malaysia to properly erect maritime "fence" over its territorial watersof the Straits of Malacca and Singapore.

Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (LOSC) clearly states that a coastal State may claim up to 12-nautical miles (approximately 22 kilometres) of territorial sea from the baseline of the coastal state. The coastal State has absolute sovereignty over its territorial sea area which consists of both the seabed and the marine waters within that specified zone.

Beyond this 12-nautical miles limit, a coastal State could no longer exert sovereignty but it could however, exercise sovereign rights up to 200-nautical miles (approximately 370 kilometres) of "exclusive economic zone" (EEZ), otherwise known as the fishing zone.

However, the EEZ boundary involves only the marine waters in that zone without including the seabed area. The seabed area is described as the "continental shelf," usually rich in minerals and petroleum deposits, where the LOSC allows a coastal State to claim up to 200-nautical miles of continental shelf measured from its baseline.

In certain circumstances, the boundary line demarcating the EEZ and continental shelf could be different between two neigbouring coastal States. Hence, a coastal State may possess sovereign rights to extract minerals from the seabed but could not exercise its rights to exploit fisheries resources in the body of marine waters over the seabed of the same area, as the sovereign rights to fish in these marine waters may belong to a different state.

The history of maritime boundary delimitation in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore goes back to colonial times. The earliest agreement can be traced to an Anglo-Dutch treaty in 1824 entered into in London, that divided maritime South-east Asia into two parts; Singapore and the Malay Peninsula were placed under British dominion while the areas of the Malay Archipelago south of the Strait of Singapore were placed under Dutch control.

However, there was no precise boundary delimitation that divided the Strait of Malacca into the British and the Dutch dominions. The treaty merely explained the spheres of influence of the Dutch and the British in the Malay World.

The length of the Strait of Malacca runs mostly between the Malaysian and Indonesian territorial waters. Considering this, Malaysia and Indonesia concluded an agreement on March 17, 1970, dividing the territorial seas of both countries in the Strait of Malacca.

An agreement was signed between both nations to delineate continental shelf boundaries in the Strait of Malacca a year earlier in 1969. The seabed boundary line between the two nations coincides with the territorial sea boundary line in most sections of the waterway.

At this time, there was no agreement on EEZ boundary line negotiated. EEZ was not considered one of the zones of maritime jurisdiction until the LOSC came into force later in 1982.

To the south, the territorial sea boundary line slightly deviates from the seabed boundary limits in favour of Malaysia. Most of the southern part of the Strait of Malacca is too constricted (less than 200 nautical miles in breadth) to have an EEZ corridor.

Despite having agreed territorial sea and seabed boundaries, there is yet to be an agreement between Indonesia and Malaysia on the delimitation of their EEZ boundary in the Strait of Malacca. The absence of a precise EEZ boundary delimitation in the northern part of the Strait of Malacca has generated difficulties for Malaysian and Indonesian fishermen in determining which maritime areas of the Strait are permissible for fishing, creating a zone called the "grey area."

Beginning 2008 up to 2012, the Malaysian and Indonesian authorities have been apprehending hundreds of fishermen of either countries in the "grey area" for allegedly committing illegal fishing, an offence under the law of both nations.

As the discussion on EEZ demarcation is still ongoing, the Malaysian and the Indonesian authorities have agreed in February 2012 to no longer arrest fishermen of either countries in the "grey area" but instead would only instruct them to leave the area.

In its new map of 2017, Indonesia does not use the same boundary line (used for continental shelf as agreed upon in 1969) to draw its EEZ in the Strait of Malacca.

Alternatively, Indonesia is applying the "equidistance principle" in drawing its EEZ line. Malaysia on the other hand is asserting that the continental shelf line should be the same with the EEZ line.

It is however not entirely peculiar to have different demarcation lines for EEZ and continental shelf and this is in fact practised between Indonesia and Australia in the demarcation of the Timor Sea. The EEZ line favours Indonesia while the continental shelf line provides Australia with a larger continental shelf area.

Likewise, the EEZ line Indonesia is asserting definitely provides Indonesia with a larger EEZ area in the Strait of Malacca as the line is pushed towards the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia, undermining Malaysia’s sovereign right over EEZ in that maritime area.

This is just one of the many overlapping maritime claims taking place among nations in South-east Asia. As far as this case is concerned, Malaysia should continue re-negotiating with Indonesia to ensure that the same boundary line is used for both EEZ and continental shelf between the two countries in the Straits of Malacca.

The application of one demarcation line would allow better management, surveillance and enforcement of laws in this particular maritime zone of the Straits of Malacca.

* Mohd Hazmi Mohd Rusli is a senior lecturer at Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia and a visiting professor at the School of Law, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail Online.