OCTOBER 12 — Ten to 12 and the idyllic picnicker is lying flat on the bus stop bench, his motorbike parked next to him.

It’s a fine-looking bus stop, tiled all over, but no bus route on this road. Just another deadweight investment loss for Kajang Municipality and its impeccable planning.

The food delivery guy naps as he waits for the impending lunch time rush, luxuriating in the 150 API (Air Pollution Index) quality Cheras oxygen on a Monday before an order comes in — the day before a scheduled 48-hour water disruption for Klang Valley’s nine million inhabitants.

There is so much to weigh-in on. Local councils’ inclination to own disused constructs, to how bad water rationing gets in public housing buildings where most city delivery guys live — in high density housing with low infrastructure, water cuts are hell. And there is the haze just about to get nastier — but no worries, Indonesia and the Malaysian plantation companies operating in Sumatera are actively looking out for us. Can’t be sure, the visibility is poor for myself to judge. Fortunately, our government’s vision is 20/20.

For this time, it’s asking if delivery riders are failures.

Mind you, this work is not easy. On foot and bike from one restaurant to the next nondescript condominium, for a machine calculated fee and rarely a tip.

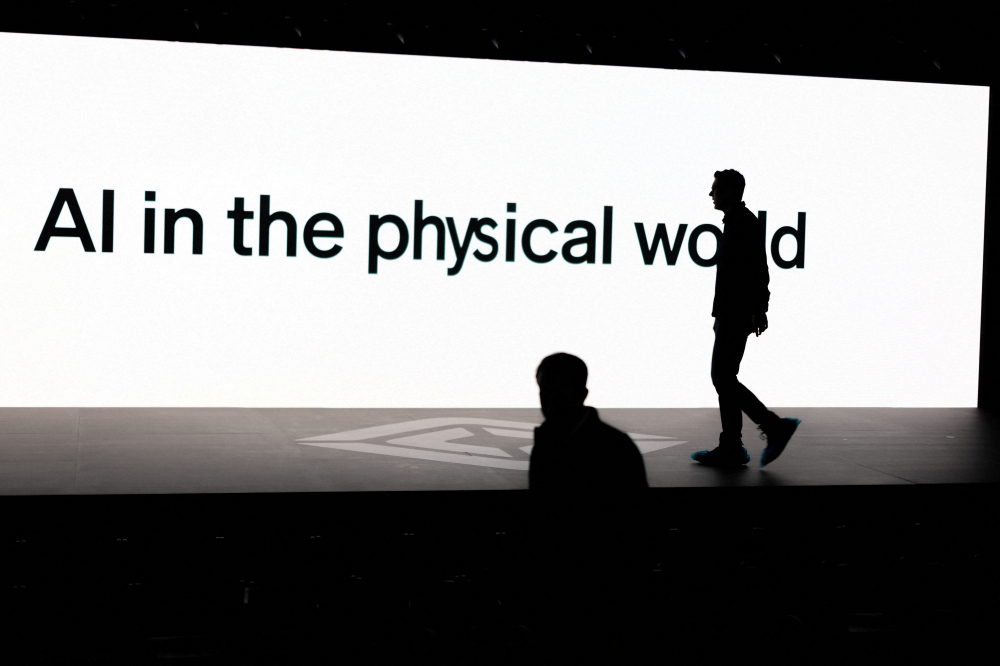

The delivery guy is the ultimate manifestation of the modern blue-collar worker, in technology reliant employment which requires a lot of physical exertions.

For those unaware, Malaysians by large disdain physical work. It was put into our bloodstream over the last 40 years, that the future for Malaysia is up and further up the value chain.

Work ties are good. Tying a bag to the back of the bike to carry takeaways, bad, very bad.

Malaysia changed from the 70s, at the advent of the petro-economy. Demographics certainly too. From “very rare a graduate in our village” back in the day to “twice as many graduates as datuks” these wistful days.

Petro dollars, which peaked in the early 80s to the late 2000s, emboldened our policy makers to envision Malaysia similar to its Middle East cousins. Where citizens cruise to lunch appointments in SUVs gorging on cheap petrol while fixed-contract migrants mind the store, petrol station, mall and everything else.

Which is why despite wages remaining stagnant, and more graduates taking on lower-paying jobs in an employer’s market, they still want an office job — with air-condition.

The air-condition separates citizens from the migrant menial labour.

In fact, many Malaysians decline better paying physical work and opt for dead-end clerical roles as long as it comes with an electronic pass-card and lanyard used to access through a turnstile to the lifts. Pay is secondary to a decent address, which translates to prestige.

Only the migrants do those jobs, is the sentiment. Those jobs of lifting, carrying, serving or collecting out in the sun or in a F&B outlet.

So rather than advocate and negotiate for better pay for physical labour, Malaysian labour opts to forgo the field.

The reference to the delivery guy, a more recent phenomenon, and increasing numbers of them indicates the tide today here is more Philippines than UAE. The current mismatch between qualifications, capacity or both and the prevailing economy job structure will force Malaysians to menial jobs. Regardless of how many online meetings with global CEOs the prime minister arranges. Regardless of foreign labour already inundating the space.

But is that failure for Malaysians?

My family is working class. Dreary work is how our families were built, and yes, more than a few made it up and further up that value chain. Just as many remain in the physical labour space.

In the early 1990s, graduates could just walk into well-paying jobs and a career. Today, the situation is terribly different. In 2023, a degree does not guarantee a job, let alone a well-paying job.

Many today emerge with nonsensical degrees from sub-par universities and colleges, therefore highly unemployable. The only thing the degree time gave them was a student loan debt. They join another queue of those who never did pursue tertiary education. Together, it is a bloated nightmare.

The petro-dollar economy has passed us and now it is time to change the tune.

A wake-up call is not the worst option. It is alarmist, but how is it walking indifferently around in a building on fire to not panic the rest, not irresponsible?

The cultural “Scarlet Letter” stuck to menial labour has to be confronted, and yes, defeated. In the present, those with minimum abilities abhor menial labour due to the social connotations tied to it and render it as the undesirable option only to be taken as a last resort.

In the aftermath of Covid-19, with the cap on new migrant labour on, the government chose to relax entries rather than urge Malaysians to fill the gaps.

But that can change. With leadership, it can.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim should take a cue from his mentor and predecessor Mahathir Mohamad from the slogan-weaving days of the early 80s through to the 90s. Look East Policy, Buy British Last, Malaysia Incorporated, Productivity Ant, Industrialised Malaysia, Leadership through Example were some of the slogans to set the tone and direction of the country.

We believed we were something before it actually materialised. Neat trick by the government back then.

Anwar should normalise physical labour as incredibly valuable work to propel the country forward.

If businesses feel Malaysians do not fare well, then it is the government’s job to reassure industries, while on the other hand encourage Malaysians to take up the labour challenge, rather than wait for jobs in offices which never materialise.

Or worse, the government has been complicit in offering short term civil service contracts to the young to keep unemployment rates low.

Government should be the intermediary between industry and local workers. Promise productivity to one side, promise better pay and benefits to the other — which aids to remove the stigma attached to menial labour.

The biggest problem with our government, this and all before it, they tend to tell the people what the problem is as though the people are distanced from the problem.

The problem is lived by the people. Nothing is more personal and immediate as work.

Perhaps if the government talked to the people about how we need to fill those jobs — the pretty ones and the not so pretty ones — possess the determination to reassure the rakyat of a safety net then the people react.

Respond to the country’s call to meet this new century’s challenges.

While urging, insert a sense of pride in labour.

The delivery riders bring joy to homes and offices. They make other people’s productivity rise. They reduce the number of families driving around and grinding traffic to a halt. They prevented tens of thousands of small food outlets from bankruptcy during the pandemic.

Yet, that’s not the story.

The government almost acts ashamed it has that many riders, as a symbol of economic failure. And all other Malaysians as labour.

If only there was a government which wised up and used the situation to empower Malaysians rather than deflect. There should be more Malaysians in physical labour and it is not a mark of shame. A nation powering itself with all its people is a point of pride.

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.