KUALA LUMPUR, June 16 — If you are born in Malaysia and are a Malaysian, do you take it for granted that your children and grandchildren will also be Malaysians and enjoy the same privileges as you?

A Malaysia-born family in Taiping, Perak has found themselves struggling through three generations of statelessness — a situation where they are not citizens of any country at all.

Malaysia, which has been their only home their entire lives, does not consider them to be Malaysians.

This is despite them being able to trace their roots five generations back to a Malaysian couple, with this first generation being born in this land even before Malaysia was formed in 1963.

Each new generation of this Perak family now inherits the same stateless status and its harsh consequences of being stuck in a cycle of hardship and being deprived of what Malaysians enjoy: access to education, job opportunities, affordable healthcare and more.

On May 24, six stateless family members spanning three generations filed a lawsuit against the government at the High Court in Taiping, asking to finally be officially called Malaysians.

How and why did they become stateless?

Based on court documents sighted by Malay Mail, this is the Perak family’s story as told to the High Court:

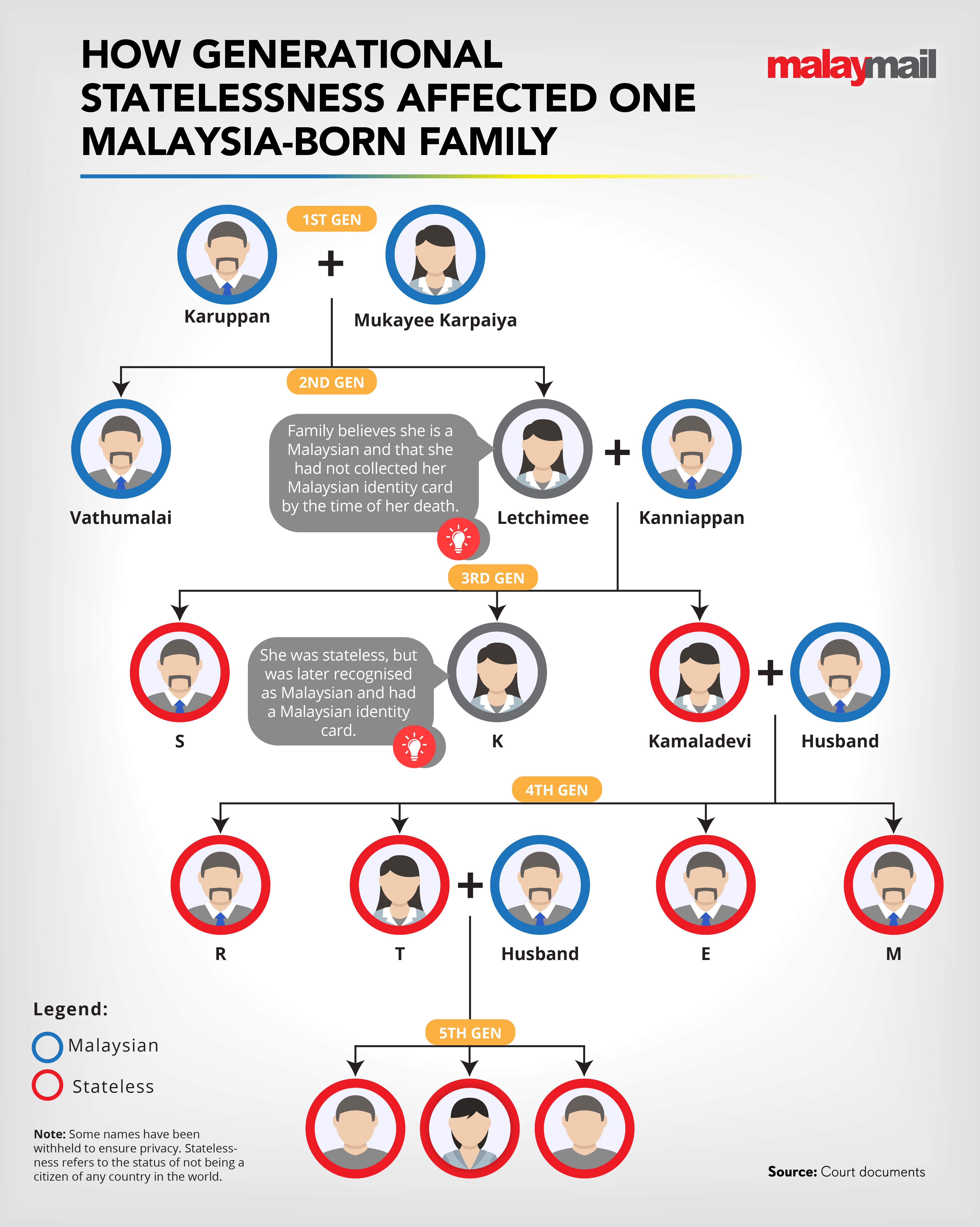

Johor-born Kamaladevi Kanniappan, 45, is in the third generation and is stateless; and all her children and grandchildren are also stateless.

Kamaladevi’s Malaysian grandparents (the first generation) married customarily and gave birth in Malaysia to a son, Vathumalai and a daughter, Letchimee (the second generation).

When Vathumalai and Letchimee were young, their stepfather pawned their birth certificates to a moneylender to borrow money.

Later, when Vathumalai was growing up, he managed to get back his birth certificate after pleading with the moneylender and was able to use it to get a Malaysian identity card.

Vathumalai later managed to pay off the loan and retrieved his sister Letchimee’s birth certificate, but she went on to customarily marry a Malaysian man and gave birth to three children in Malaysia (third generation). The marriage and their birth were before she received her Malaysian identity card.

This third generation are Kamaladevi, her elder brother S and her elder sister K. Unlike the two other siblings who remained stateless, K later managed to obtain Malaysian citizenship.

Without an identity card, Kamaladevi’s mother Letchimee could not register her marriage with her Malaysian husband at the National Registration Department (NRD), which caused Kamaladevi to be considered an illegitimate child or a child born out of wedlock.

After an earlier attempt in 1976, Kamaladevi’s mother Letchimee on March 25, 1985 tried applying again with the NRD for a Malaysian identity card and was this time issued a temporary identity card.

By the time she died in 2003, Letchimee only had this temporary identity card, Kamaladevi said. Kamaladevi asserts that her Malaysia-born mother is a Malaysian and believes she would possess an identity card but did not collect it from the NRD.

The temporary identity card referred to by the family is an NRD-issued document titled “Surat Pengenalan Sementara dan Kenyataan Penerimaan Permohonan Satu Kad Pengenalan” (Letter of temporary identification and statement of receipt of application for an identity card), with the document stating “belum dikeluarkan” (not yet issued) for the information on the colour of the identity card.

The document also carried a reminder for applicants to return the letter when they come to collect the identity card, and to notify the NRD office which issued the document of their new address if they have moved places.

With Kamaladevi’s Malaysian father being sick and with his death in 1988, the family had to stay at relatives’ houses and faced financial hardship, with Kamaladevi being taught rubber tapping and having to start working at the age of 12 with her cousin at the estate.

The cousin told the High Court that Kamaladevi did not get to have a proper education as she was not recognised as a Malaysian.

In 1996, Kamaladevi married a Malaysian man, but — just like her mother Letchimee — could not register the marriage with the NRD as she did not have a Malaysian identity card.

Kamaladevi gave birth to four children who have birth certificates showing they were born in Malaysia. But all four children were not recognised as Malaysians, as Kamaladevi’s inability to register her marriage as a stateless person resulted in them being denied citizenship too.

Kamaladevi’s husband died in October 2009 and the family left behind experienced hardship worsened by their stateless status, including limited job prospects due to discrimination and deprived of the same social protections and support or benefits that Malaysians enjoy.

Hoping to change the fate of her children and grandchildren, Kamaladevi in 2015 applied to the NRD for late registration of her own birth, but was rejected three years later in 2018 without any reasons given.

After the Department of Chemistry Malaysia’s December 2019 DNA test results verified Kamaladevi is related to her Malaysian uncle Vathumalai and that her youngest son M is her biological son, Kamaladevi in May 2021 applied again for late registration of a birth certificate.

Kamaladevi was on April 26, 2022 granted a late birth certificate which recorded her citizenship status as “maklumat tidak diperolehi” (information not obtained), which meant she was still not recognised as a Malaysian.

Kamaladevi’s daughter and grandchildren are stateless too

Kamaladevi’s daughter T’s birth at Hospital Teluk Intan was registered late and she was given a birth certificate in May 2009, which stated her citizenship status to be “belum ditentukan” (yet to be determined).

Kamaladevi’s daughter T could attend school as a child, but she was not given equal opportunity to education and was denied permission to even register for the qualifying examination of PMR in Form Three of secondary school — simply because she lacks Malaysian citizenship.

T said she was left with no choice but to start working at a young age to survive, working in menial jobs and taking up any available opportunities such as being a domestic cleaner, gardener and grasscutter.

Lacking Malaysian citizenship, T could not get stable and long-term jobs, and could not even officially register her marriage with her Malaysian husband in 2014 as she lacked official documentation except for her birth certificate.

“Being stateless has grievously denied me the fundamental right to get married, adding to the weight of despair that already burdened my life,” she said.

T gave birth to three children at hospitals in Taiping and Ipoh but faced the “cruel reality” of seeing their birth certificates also stating their citizenship status as “belum ditentukan”.

T’s three children — or Kamaladevi’s grandchildren — too have become stateless, and also face the same lack of education opportunities and equal access to affordable healthcare.

Even while giving birth to her three children or seeking medical treatment, T had to pay significantly higher fees compared to Malaysian citizens, which placed an additional burden on her.

Obstacles to a better life

Kamaladevi’s youngest son M, who was born at Hospital Taiping and turns 22 this year, said he had to drop out in just Form One due to his inability to furnish citizenship-related documents to the secondary school.

Like his elder sister T, he had no choice but to start working young and accept any odd jobs out of desperation, with his lack of citizenship also leaving him caught in a cycle of temporary and precarious employment.

As a contract labourer currently, M said being stateless has prevented him from buying a vehicle for daily commutes and to get better jobs.

“Due to my lack of citizenship, banks are unwilling to provide me with a loan, depriving me of the means to improve my life and enhance my standard of living; thus, keeping me trapped in a cycle of limited opportunities,” he said, adding that his stateless status has also affected his mental health and left him depressed.

Being stateless in Malaysia also means being unable to open a bank account or to get a driving licence, based on the reported experiences of other stateless persons previously.

Tragedy in the family

Kamaladevi’s two elder sons R and E died by suicide, which the family believes had been contributed to by the devastating consequences and burden of being stateless — including being denied education opportunities and equal job opportunities, and the hardship and difficulties from their lack of citizenship.

“Tragically, the weight of the hardship became unbearable for two of my sons,” Kamaladevi had told the court, while Vathumalai and Kamaladevi’s youngest son M assert that the weight or burden of statelessness had become unbearable for R and E.

When contacted by Malay Mail, Maalini Ramalo who is director of social protection at the non-governmental organisation Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) — which assists stateless persons — spoke about the difficulties faced for cases of childhood statelessness.

“Being stateless in Malaysia is an actual state of vulnerability despite having ‘significant and stable ties’ with the country, with multiple hurdles to access the very basic rights and denied dignity to live,” she said.

Maalini said it is important to recognise the existence of childhood statelessness in Malaysia which could be contributed to by system bureaucracy and said being stateless results in having “few avenues for upward mobility, leaving generation after generation to toil in poverty and obscurity”.

Maalini said childhood statelessness includes those who were adopted, abandoned at birth, or born out of wedlock, and the resulting stigma, shame and feeling unwanted could lead them to be frustrated and have suicidal thoughts.

She said such struggles faced by stateless persons could include children who did not know they were adopted but suddenly discovers this due to them not having Malaysian citizenship; children who are stateless because their birth parents abandoned them without leaving any information; and children who are called “born out of wedlock” and denied citizenship because their parents could not register their marriage before birth; and being unable to further their studies like their peers despite their family being able to afford it due to their stateless status.

Asked for advice for stateless persons who are feeling frustrated and may have depression or suicidal thoughts, Maalini said it would be helpful in such situations to reach out to organisations like DHRRA — which is in the process of enabling better access to opportunities for stateless persons.

“It’s important to seek assistance from trusted persons, or get peer support from stateless communities and connecting to other stateless persons who may inspire them and provide hope and help them shift from feeling bitter or defeated,” she said.

“The best support they have received is from a person who is also stateless, the moment they get to know that person and see how they have been dealing with it, that really helped them so much,” she added.

She said many stateless persons and their families still cling on to hope, but that many had also reached out to or informally organised themselves into stateless support communities such as the Stateless Malaysians Citizenship Movement for peer support.

“Being part of these groups has positively enabled their better access for mental support and basic rights,” she said.

Maalini said there is hope for stateless persons and they can reach out to DHRRA for assistance in pursuing further studies and employment, adding that more stateless individuals have been able to go for tertiary education and be employed.

“Today, I can name stateless persons who have completed their law or engineering studies, pursuing their medical degree. Some have opted for online businesses and chose digital courses to earn an income through designing and digital illustration. Families who have turned enablers for another stateless family. So many untold stories of their resiliency,” she said.

Asking for help from the courts

Now, Kamaladevi, her son M, her daughter T, and her three grandchildren born to T are going to the courts to ask for recognition that they are Malaysians.

In the lawsuit, they named five respondents to the lawsuit, namely the Registrar of Births and Deaths, the Registrar-General of Births and Deaths, the director-general of National Registration, the home minister, and the government of Malaysia.

The Perak family is seeking for seven specific court orders, including for declarations that they are automatically Malaysian citizens under the Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b) read with either Section 1(a) or Section 1(e) of Part II of the Second Schedule of the Federal Constitution.

They also want court declarations that they have the right to be issued both birth certificates and identity cards with the status “Warganegara” or citizen.

Kamaladevi and her daughter T want a declaration that they have the right to register their marriage with the NRD under Malaysian laws, and a declaration that the government had violated their rights under the Federal Constitution’s Article 8(1) — which guarantees equality and prohibits discrimination.

When contacted by Malay Mail, the Perak family’s lawyer Shugan Raman said the lawsuit is scheduled for its first case management at the High Court in Taiping on June 28.

*If you are lonely, distressed, or having negative thoughts, Befrienders offers free and confidential support 24 hours a day. A full list of Befrienders contact numbers and state operating hours is available here: www.befrienders.org.my/centre-in-malaysia. There are also free hotlines for young people: Talian Kasih at 15999 (24/7); and Talian BuddyBear at 1800-18-2327(BEAR)(daily 6pm-12am). DHRRA also operates a careline that provides free mental health support and counselling: 03-7887 3371 / 03-7887 7271.