AUG 30 — Bring on the electric vehicles, plug in your solar panels, and buy some carbon offsets. Such mainstream thinking on climate change is most reflective of the perspective of the elite and corporations of the Global North. Developing countries of the Global South mistaking these solutions for their principal climate action may find themselves unprepared to face climate vulnerabilities.

Climate change might seem like a purely technical and scientific issue of reducing pollutants - greenhouse gas emissions, especially carbon dioxide - that are presenting a threat to the environment and human life via global warming. Climate action often focuses on shifting our energy sources from fossil fuels to lower-impact alternatives such as renewable energies, and halting the loss of forests and other carbon sinks that absorb carbon dioxide.

In reality, climate change is more complex. Rising global average temperatures are already causing extreme weather events such as floods, heat waves, droughts, and wildfires. These cause damage and loss to lives, livelihoods and property. Melting glaciers and sea ice lead to coastal erosion, sea level rise, storm surges, and breakdown of ocean circulation systems. Alongside efforts to stabilise the climate many communities will have to adapt to the climate changes that are already happening and will continue to happen for some time to come.

There is a third dimension of climate action that goes beyond physical causes and effects. Climate justice tackles the ethical and political distribution of responsibility for the climate crisis. Not all countries are equally responsible for causing climate change. But people who are genuinely concerned about the climate crisis sometimes assume Malaysia shoulders an equal burden to developed countries. Policies and climate action proposed based on this assumption risk being unjust if they lead to disproportionate burdens or fail to address our direct climate vulnerabilities.

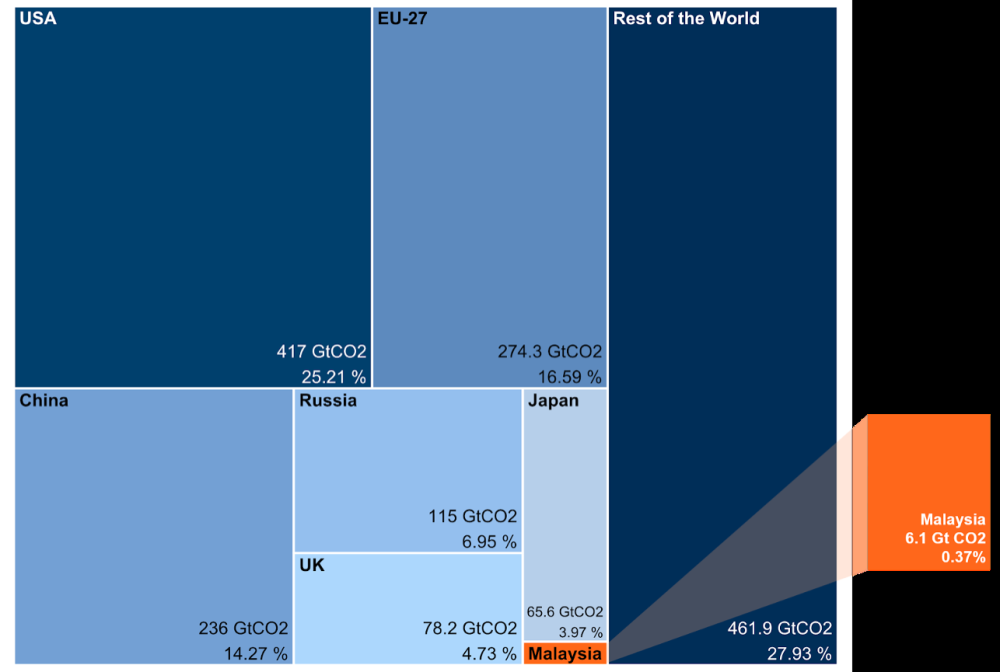

Historical emissions matter because carbon dioxide persists in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Massive long-term emitters have the greatest impact on our climate. Just six nations are responsible for over 70 per cent of historical global greenhouse gas emissions. In descending order of magnitude these are the United States, the European Union, China, Russia, the UK, and Japan. Emission proportions are skewed even more to the North when we take into account China’s huge population of nearly 1.4 billion, more than the other five combined. What share of global emissions is Malaysia responsible for? A mere 0.37 per cent as of 2020.

Under the United Nations’ treaties, a country’s responsibility and ability to address climate change is proportional to its emissions, technological and financial capability. Rapid big cuts by big emitters will stabilise the global climate more then big cuts by small emitters. Because the climate changes we are experiencing are primarily driven by global factors we need to cut emissions on a global scale in order to save Malaysia at the local level. Drastic cuts in Malaysia’s own emissions will not be enough to move the needle because our emissions are comparatively small. Global factors complicate assumptions that cutting domestic emissions leads to direct reductions in domestic climate vulnerabilities.

If we want to save Malaysia from the ravages of climate change we need to link science to action that is appropriate to our circumstances.

The electric vehicle transition features prominently in Western media. Displacing Malaysia’s dependence on single-occupancy fossil-fuelled cars in favour of greater public transportation and electric vehicles where appropriate would be an environmental good. But it will not stop the seas from rising, floods from worsening, and heatwaves bedevilling us because Malaysian emissions are comparatively low.

Shifting our electricity fuel mix rapidly away from coal towards renewables is environmentally desirable, but how do we ensure rising costs of electricity production don’t punish the vast majority of households who are struggling with low wages, inflation, and pandemic recovery?

Mass deployment of electric vehicles, renewable energies, costly carbon capture and sequestration - the kind of solutions proposed to deliver deep cuts in the biggest polluting countries - are they appropriate for the likes of Malaysia, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and North Korea?

I mention the last five countries because they have emitted a comparable amount to Malaysia, though our development results have been considerably greater when considered in terms of gross national income. Malaysia’s development gains have been relatively emissions efficient by comparison. Yet, we do not have anywhere near the same technological and financial capability as the ‘Big Six’ polluters who are also Great Powers of world diplomacy.

We need diplomatic pressure on the biggest global polluters to undertake deep cuts that will save all of us. Malaysia can’t exert enough diplomatic pressure on its own, so we need to work en bloc with a critical mass of developing countries. This is a role from which Malaysia has exercised leadership in the past.

Nationally and locally, we should be focusing on climate adaptation measures: urban greening to tackle urban heatwaves, flood mitigation and better planning to minimise the impact of the great rains, mangrove restoration and engineering works to combat coastal erosion. These measures are not rocket science, we have the local expertise and technology to pull much of this off, unlike with energy transition measures. However, we need to tap into more national and international financing to bring these solutions online. It can be done. Think City in Penang has recently secured US$10 million (RM44 million) in climate adaptation financing to tackle heat and floods.

We must also conserve and expand our precious forests and coral ecosystems because the carbon they absorb allows the rest of our economy and society to keep down net emissions from using currently available energy resources - as much as 76 per cent in 2016. Selling the rights to these as carbon credits to international buyers effectively cedes our strategic development reserve to richer countries who should be cutting emissions at source with their technology and finance, not with our forests. Sustainably financing ecosystem conservation is a critical and neglected element in preserving our development policy space for future generations of Malaysians.

This is a month of national history where we look back into the past for inspiration. In order to prepare for the future we must recognise what is useful and appropriate for our national journey. In order to tackle the climate crisis we do need to cut emissions and respond to current and emerging impacts. But the biggest cuts in emissions need to happen outside of Malaysia - from the Big Six Great Polluters - and no one but ourselves will protect our communities and nature from the ravages of climate change. We will protect them best by pursuing climate justice internationally and upscaling adaptation measures locally. Our current national and corporate focus on net-zero emissions targets around 2050 and beyond do not address where either emissions and impacts are really happening. This ultimately implies a rethink of national climate strategy from the top down, combining strategic purpose with data and science, within a framework of climate justice.

* Yin Shao Loong is a senior research associate at the Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) where he focuses on climate change and industrial policy. Twenty years ago he helped draft the Bali Principles of Climate Justice which were launched on 29 August 2002 at the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development. This article summarises a longer paper under development. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Khoo Wei Yang and Chanel Ng Siau Ling in compiling data. The views expressed here represent those of the author.

**This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail