KUALA LUMPUR, July 12 — Three stateless siblings born in Malaysia to a Malaysian father are now officially Malaysians after 13 years of waiting, following their High Court win last Monday.

The eldest, who will be turning 26 this year, expressed happiness as he and his siblings look forward to giving back to Malaysia — the country where they had lived their whole lives.

“My siblings and I are very happy with the decision going in our favour. We have been fighting for our citizenship for over 10 years and this is a huge step forward for us.

“We can finally experience the things we never got to do and have the opportunity to contribute back to the nation we love,” he told Malay Mail via their lawyer.

Their names have been withheld to protect their privacy, with the three siblings known as K1, K2 and K3. The latter two will turn 21 and 19 later this year.

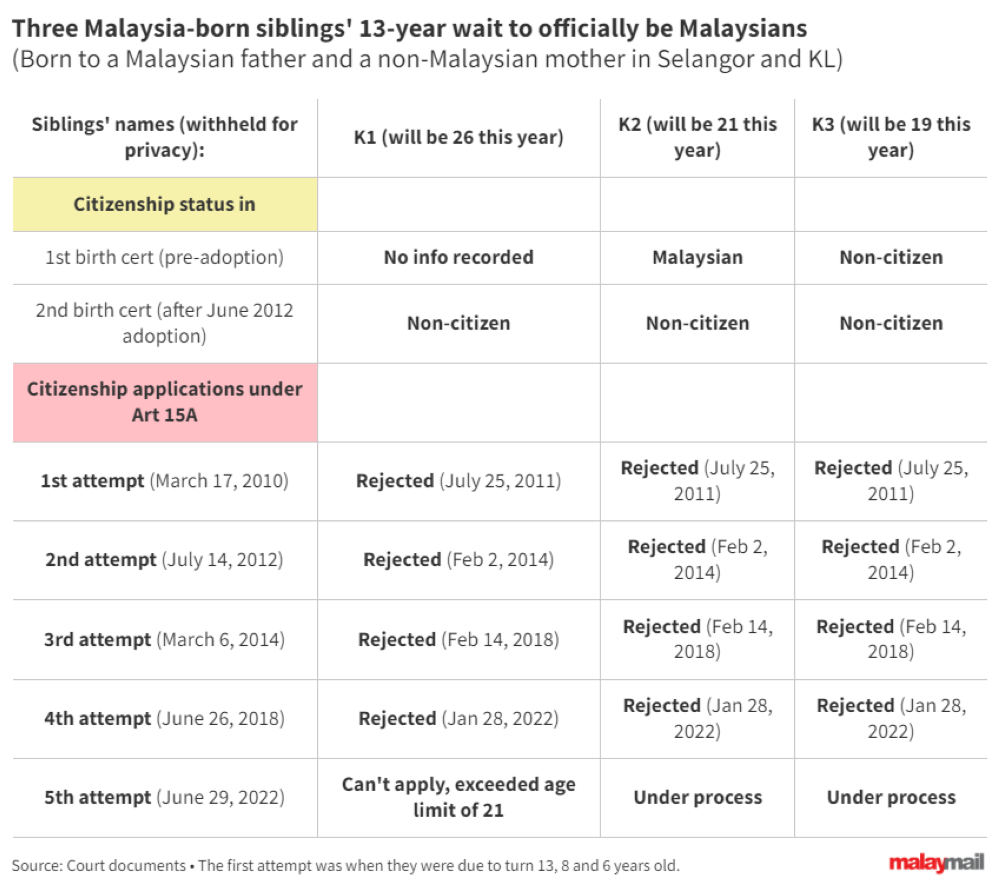

Previously, the three had tried five times — except for the eldest child who ran into an age limit — to apply to be recognised as Malaysians. The first time they tried applying was when they were 13, eight and six.

Following the High Court’s decision, the trio’s lawyer Larissa Ann Louis said that this Selangor family is finally able to belong to Malaysia.

“I am glad that the three siblings are finally recognised as citizens of Malaysia. Everyone has a desire to belong and today, this desire was fulfilled for this family,” Larissa told Malay Mail.

On August 24, 2022, the three had filed a lawsuit via an originating summons in the High Court here against the national registration director-general, the Home Ministry secretary-general and the Malaysian government, seeking six court orders.

According to Larissa, High Court judge Datuk Amarjeet Singh Serjit Singh on Monday granted four court orders sought by the three siblings, including a declaration that they are Malaysian citizens.

The High Court judge also ordered the government to issue birth certificates and identification cards (MyKad) stating the trio as Malaysian citizens within 30 days from the court order, and ordered the national registration director-general to register and update the three siblings’ names in the registry.

How did they end up stateless?

Based on court documents, K1 and K2 were born in private hospitals in Selangor and K3 was born in a private medical centre in Kuala Lumpur, but have been denied Malaysian citizenship for years now and are also not citizens of any country in the world. In other words, they are stateless.

Their Malaysian father and non-Malaysian mother married through a traditional Chinese wedding, but this marriage had not been registered under Malaysia’s laws. (This would later be the reason used by the government to reject the trio as Malaysians, as it only recognises registered marriages as valid marriages.)

Despite being born to the same parents, all three siblings were issued different birth certificates upon birth: K1’s did not record anything about his nationality status, K2’s stated him as Malaysian, K3 stated her as non-Malaysian.

K1 went to school without issues, but his father was in for a shock when the child turned 12. The father had gone to the National Registration Department (NRD) to apply for K1’s identity card, but was told it would not be issued due to the lack of marriage papers between the parents. The government retracted K1’s Malaysian citizenship without any procedures, K1 told the court.

When K2 was aged nearly seven, problems arose when the father sought to enrol him for school. The child’s Malaysian citizenship was removed without procedures due to the lack of a registered marriage between the parents, K1 said.

In 2010, the father applied for his three children to be Malaysian citizens under the Federal Constitution's Article 15A.

Article 15A enables the Malaysian government to register anyone below the age of 21 as a Malaysian citizen, under such “special circumstances as it thinks fit”.

But the first citizenship attempt was rejected slightly more than a year later, with the rejection letters stating the reason as failure to register the marriage of the parents — who are non-Muslims — under the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce Act) 1976.

After the first rejection, their Malaysian father had applied to adopt his three children, after receiving advice from lawyers that it could help him obtain Malaysian citizenship for them.

In June 2012, he obtained a court order to legally adopt his own three children and was named as their father in their second birth certificates.

But he was shocked to find that the second birth certificates now stated all three children to be “non-citizens”, when he himself was Malaysian and their biological father. In fact, DNA tests carried out by the Department of Chemistry Malaysia in 2014 — after the second citizenship bid rejection — confirmed he is the biological father of all three children.

After the adoption, the biological mother — who is a citizen of the Philippines — disappeared from the family’s lives. The mother has been untraceable since then, despite the father’s efforts to find her.

The three siblings’ second citizenship attempt in July 2012 was rejected in February 2014, while their third attempt was rejected in February 2018. Their fourth citizenship attempts in 2018 were all rejected in January 2022.

By the time his fourth citizenship application was rejected, K1 was turning 25. This meant he could no longer apply under Article 15A as he had exceeded the age limit.

While K1 wanted to try applying under the Federal Constitution’s Article 19 for citizenship by naturalisation, the government did not even allow him to have the Article 19 application form as he did not have a passport or entry permit into Malaysia or a temporary resident identity card (MyKAS).

By their fifth attempt in June 2022, K2 and K3 were turning 20 and 18. Their fifth citizenship applications have been “under process” since then.

Only the first rejection came with a reason. The other attempts were all rejected without any reason stated.

Difficulties while growing up

K1 told the High Court of the three siblings’ struggle while growing up, where they were emotionally affected and mentally distressed as they were frequently teased and mocked by schoolmates who labelled them as “foreigners”.

He said they also frequently faced difficulties in progressing to the next grade as their schools will always question them about their citizenship status at the start of every school year.

As stateless persons, K1 said they were unable to peacefully enrol in schools or universities or to find work, as they did not have identity cards and no nationality at all.

“This has caused much hardship to our family. This uncertainty causes a lot of stress to my family,” K1 said.

Despite their struggles, K1 said he and his siblings achieved good results while schooling, adding that they truly love Malaysia as they are not citizens of any other countries at all.

K1 said the trio have also not committed any crimes and have close ties with the local community.

As stateless persons living in Malaysia, K1 and his siblings face difficulties in continuing their studies to the tertiary level, applying for scholarships, getting driving licences and finding work.

They would also not be able to open bank accounts or apply for any bank loans or carry out any online transactions, and would not be able to register their marriages (which could lead to their children becoming stateless too) in the future, and would also not be able to visit any countries.

On Monday, the High Court declared the three siblings as Malaysians in line with the Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b) and Section 1(a) of Part II of the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule.

Section 1(a) is a condition for those born in Malaysia to be automatically entitled to Malaysian citizenship, with the requirement being that at least one of the parents is a Malaysian or permanent resident when the person was born.

Larissa noted that the Malaysian government intends to amend certain citizenship laws in the Federal Constitution, but said some of the proposed amendments will result in “more restrictions than solutions”.

Apart from proposed citizenship law changes to grant automatic citizenship to Malaysian mothers’ overseas-born children, Larissa urged the government to reconsider and carry out in-depth research on the other proposed amendments.

“Childhood statelessness and existing context of statelessness among adults will not be addressed with the proposed amendments. Instead, more lives will be deeply affected,” she said of the other planned amendments, urging the government to instead propose amendments to help solve the long-running issue of statelessness in Malaysia.