TANJUNG KARANG, Aug 1 — In the heart of Selangor’s idyllic northern belt, where verdant fields meet expansive waters, a quiet crisis is unfolding as the once-bountiful harvests of paddy farmers and the abundant catch of fishermen steadily dwindle.

Ahead of campaigning for a crucial Selangor state election on August 12, the farmers and fishermen — the backbone of this region’s economy and culture — said they were facing a staggering 80 per cent decrease in production, threatening their very existence.

From dawn till dusk, the Tanjung Karang and Sungai Besar natives battle a myriad of challenges that hinder their livelihoods and threaten the sustainability of their age-old professions.

Against a backdrop of dwindling yields and vanishing catches, Malay Mail spoke to those grappling with this dire transformation, and delved into their desperation for sustainable solutions to their existential crisis.

The lingering smell of mud greets visitors arriving at the northern edge of Selangor, where paddy fields and the Straits of Melaka intertwine to sustain most of the residents of Tanjung Karang and Sungai Besar.

Almost a two-hour journey from the country’s capital, at Sawah Sempadan in Tanjung Karang, Malay Mail met with a mud-encrusted Razuwan Rasidin, a 43-year-old paddy farmer who spoke between supervising others ploughing his rice field in scorching hot weather.

Outwardly appreciative of his circumstances and existing assistance schemes, further probing led, however, to Razuwan expressing his concerns about the drastic decline of rice crops over the past five years.

Once, three square acres in Sawah Sempadan could yield up to a 12-tonne harvest from six months of toil, enough to cover expenses and commitments while providing enough left over for occasional seafood dinners to treat the family, he said.

Now, however, Razuwan said farmers would be “lucky” to get a third as much each season, making it hard to even meet their most basic financial obligations.

“Yes, with the right amount of effort and timing of spraying pesticide, you can get three to four tonnes by the end of the season. And then some of these farmers who do not own their fields have to pay a rent of about RM3,000 to RM4,000 [for a three-acre square of paddy field] a season.

“The price for a tonne of rice crops is about RM1,300, if you can only get three to four tonnes per season, how are you going to pay your commitments, not to mention going on vacation,” he said, with growing agitation.

Despite this dissatisfaction and the looming state election, however, Razuwan refused to make demands of either the federal or state government, saying both have already done much and that he did not want to appear unappreciative.

Carrying on farther into Sawah Sempadan, Malay Mail visited a “Tok Sidang,” the title for a customary head of a paddy farmers’ collective who is both responsible for imparting gathered wisdoms and representing their concerns.

At a local warung (a small food stall) beside a paddy field in Sawah Sempadan, 53-year-old Aini Sanusi sipped on sweetened iced tea while waiting for Malay Mail at what he later disclosed to be his self-designated tea break with peers.

A paddy farmer himself, Aini launched directly into the problems facing farmers in his collective, which were contributing to the shrinking harvests.

Besides worms and bacteria plaguing the paddy fields, he said soil in the area has grown unhealthy from decades of pesticides and other chemicals.

“I think the soil is worn out from all that work that it has done for the farmers here in the past few decades; sometimes it’s not about the farmers not getting any help from the government or they are not hardworking enough.

“It’s the soil that needs at least three months of recovery before we can start ploughing again,” he told Malay Mail with a heavy Javanese accent.

In one of the state government’s agricultural programmes, Aini said he learned about integrated farming that could help mitigate the overuse of specific pesticides without forcing farmers to leave their land idle for the long periods that would have been required traditionally.

Instead, this would allow them to grow other complementary crops in alternating cycles with their paddy plants and generate some revenue in those periods.

Aini said, however, that this was about the farmers banding together to help themselves in the long term, and not about authorities helping.

“Because sometimes when we spray pesticides on our side of the field, but our neighbour does not, the worms and bacteria will find their way to cross over to our side of the field, and then we must do it again and again; that costs a lot of money.

“If we want to do this, it requires discipline and commitment from all of the farmers here and I think it’s feasible,” he said.

Another Tok Sidang, 55-year-old Mohd Nadzef Mohd Saruwi whose skin was bronzed from years toiling under the scorching sun as a paddy farmer, said there was a way for the government to help address the dwindling harvests, albeit indirectly.

With a deeply concerned expression, Mohd Nadzef said there was a pressing need for increased research and development (R&D) initiatives specifically targeted at the paddy farmers in this region.

“I think what the government can do is buy a few squares of paddy fields here in Tanjung Karang for R&D purposes.

“I know this initiative is probably not new and has been done in other places but in my opinion, sometimes the problem that we face here in Sawah Sempadan is not the same as in Sungai Petani paddy fields,” he said referring to a district in Kedah, a state that is considered Malaysia’s rice bowl.

Despite the grievances expressed by the paddy farmers in Selangor’s northern belt, there was an underlying spirit of resilience and innovation; Mohd Nadzef spoke of an initiative aimed at bolstering their income and turning their challenges into opportunities.

Recognising the allure of their picturesque green paddy fields, some farmers here have taken the bold step of building “homestays” that offered visitors a breathtaking view of their natural vistas.

According to Mohd Nadzef, these “homestays” offered a unique experience for those seeking an immersive encounter with the rural way of life. Visitors would get to stay in traditional village houses, surrounded by the serene beauty of the paddy fields.

The initiative not only showcases the cultural heritage of the region but also serves as an added income stream for the farmers. Mohd Nadzef said the land owners had ingeniously tapped into the potential of agro-tourism, providing a sustainable and authentic experience that benefited both the local economy and the farming community.

“A lot of paddy farmers here built homestays for mostly local tourists longing for a sense of escape from their everyday urban lifestyle with concrete buildings surrounding their atmosphere. Here, they wake up in the morning and see green paddy fields, a few meters away from their doorstep.

“Apart from the main income from their yields, paddy farmers can get up to RM300 to RM400 a week from their homestays,” he said.

Similar woes for fisherfolk

While those in the neighbouring district of Sungai Besar depend on water rather than soil for their sustenance, it was an eerily similar tale of decline there.

Fishermen told Malay Mail about empty nets that had once been full of bountiful catches, and how once-abundant waters that sustained their communities for generations were now mirroring the same challenges of their paddy-farming neighbours.

Arriving in a faded blue four-wheel drive truck, teacher-turned-fisherman Mohamad Azam Shariat offered Malay Mail a warm welcome before proceeding to tend to his nets at the edge of Sungai Haji Dorani jetty, steeling himself for another trip out to sustain his family.

With a wistful look, Mohamad Azam recounted the days when he used to labour to pull the fish from his two kilometres of net that he laid out each launch.

“About six to seven years ago, I think I could consistently catch up to 20 kilogrammes of threadfin or pomfret fish. But now, particularly this year, I can only haul in about three to four kilogrammes each time I set out,” he said while rolling up tobacco for a cigarette.

Sungai Haji Dorani is home to an extensive community of over 100 coastal fishermen. Nestled along the riverbanks, this vibrant village reverberates with the sights and sounds of a dedicated fishing village.

With their livelihoods intricately intertwined with the ebb and flow of the river, these fishermen have crafted a unique bond with Sungai Haji Dorani, embracing its waters as both their workplace and homes.

Compared to his counterparts who took to fishing later in life, Hamsan Sahudin, 61, said he has been navigating the coastal waters of Sungai Haji Dorani since he was no bigger than the oar he first used to paddle out into the river.

When asked about others’ complaints of shrinking catches, Hamsan gestured with his finger towards the riverbank and the nets some fishermen set out to catch anchovies.

With a look of disapproval, he said the tightly woven nets not only caught ensnared adult anchovies but also small fry as well as other species, effectively ensuring the continued depletion of Sungai Haji Dorani’s fish population.

“We can only catch the fish’s parents, what happens if all its parents die? What are we going to catch?” he said.

According to Hamsan, the fry and fingerlings were once unintentionally caught, but this was no longer the case as they were being turned into feed for farmed fish.

Expressing concern over this practice, he said he and his fellow fishermen believed there was an urgent need to regulate against this to protect the sustainability of the river.

Hamsan and Mohamad Azam argued that these juvenile fish were vital to preserve the natural balance of the river, contributing to the replenishment and sustainability of the fish population.

By diverting the fry for livestock consumption, they expressed fear that the already declining fish population would further suffer, exacerbating the adverse effects to both the ecological health of the river and their own livelihoods.

With Selangor set for an election on August 12, the state’s northern belt with its primarily Malay residents could be a pivotal battleground to determine the next administration of the country’s richest and most industrialised state.

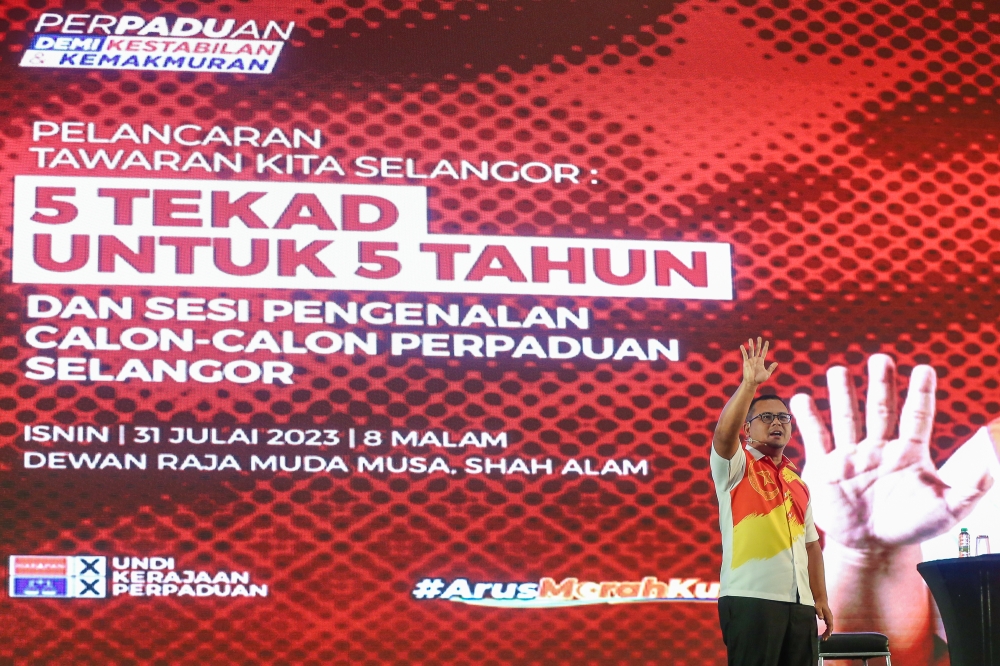

The federal Opposition coalition Perikatan Nasional (PN) will attempt to unseat the newly-allied Pakatan Harapan and Barisan Nasional, which will compete as partners for the first time in Selangor and five other states holding elections.

PN, still emboldened by its success from the wave of support for religious conservatism during last year’s general election, is banking on winning seats such as Permatang that is home to Sawah Sempadan and Sungai Burong where Sungai Haji Dorani is located.

In this political landscape, the grouses of the paddy farmers and fishermen could be an opening for either side to try and win support in the election.