FEBRUARY 15 — Many years ago, my family was in Singapore celebrating Chinese New Year. On the second or third day, we went to visit an elderly aunty, had lunch, said goodbye and went home.

The next morning, we received a phone call which I haven’t forgotten about in over 20 years. The call was from that aunt we visited the day before and she said she had been struggling to hold back her stress and anxiety.

Why? Because my parents had forgotten to give her children any ang pows whereas she had given me one.

Chinese culture, like many other cultures, is a complex blend of obligation, ritual and symbol i.e. kinda like life itself.

Inevitably there are “rules” which cannot be so easily broken without there being “consequences” (as my family found out so many years ago; oh, what eventually happened was my parents drove all the way back to that aunt’s house, gave her kids the ang pows and all was well).

The “rule” my parents forgot about on that occasion was Never Not Give An Ang Pow. But I’m getting ahead of myself...

‘Rules’ for the red packet

So, it’s the auspicious Year of the Metal Ox!

‘Tis the season (the pandemic lockdown notwithstanding) when our kids get all pumped up about “earning” lots of ang pow money and parents joke about visiting fewer people as part of a “cost cutting” exercise.

Still, one of the joys of Chinese New Year is the ang pow (literally “red envelope” in Chinese) which is a traditional and fun and awesome way for people to share wishes of luck and prosperity during the all-important Spring Festival.

Having said that, these wonderful red packets come with some unspoken “rules” which most Chinese happily adhere to but some of us (like myself) have trouble remembering each year.

“Rule” is written within quote marks because of the fluid nature of its binding quality; yes, people “should” follow these rules but there won’t be a public outcry (let alone a police report) if you don’t... even though everybody declares these are not “necessary” but you can bet your last pineapple tart they will try to keep to the “rules”, etc.

So here goes:

1. Ang pows can only be given within the 15 days of CNY

You don’t give them before and you don’t give them after. There’s some flexibility with giving them during the Reunion Dinner, I suppose, but this 15-day “window” remains default.

2. Ang pows should (like it’s name) be coloured red but pink and gold is fine too

Legend has it that this baddie dragon who was terrorising people in China was itself terrorised by the colour red.

I’m not complaining. I mean, imagine if CNY was coloured brown, how boring would that be?

Anyway, the key thing about this rule is please never use strange colours for the ang pow, especially black or white. Please God no not white — cos instead of sharing good luck with the recipients, you’ll be sharing your condolences.

3. Ang pows are always given by those from a “higher” status to those from a “lower” one

When it comes to status, there’s usually two main categories: Marital status and age.

Normally, married folks give to the unmarried folks (also usually known as, uh, children but many young unmarried adults may still qualify). Unless it’s a Boss-Employee relationship, it’s always older folks giving to younger folks.

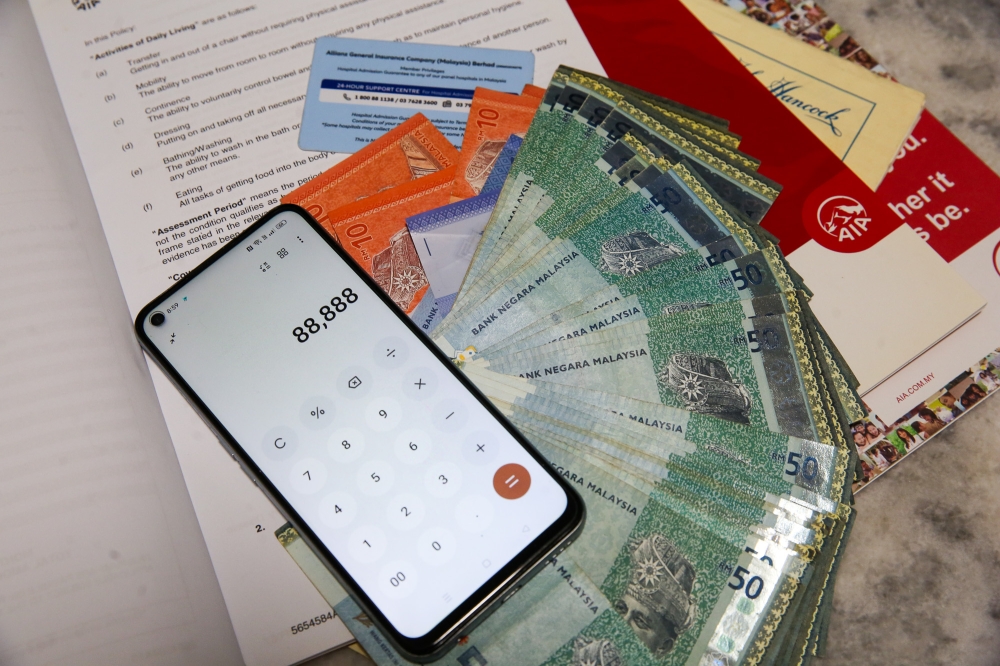

4. Ang pows should contain cash

Cheques don’t cut it and inter-bank GIRO transfers don’t count (even if some younger folks would be fine with it). This is one area where technology and new sexier “options” are given a back-seat.

This is also the reason why the two weeks before Day 1 of CNY many banks will be packed with Chinese customers asking for brand-new notes (which isn’t a rule but of course people prefer to give out fresh clean and crispy notes instead of those which have been passed around a million times).

5. Don’t give an amount which ends with 4 or “draws attention” to that number

In other words, avoid putting in RM4, RM14, RM44, RM40, RM400, etc.

The number 4 is one of the most out-of-bounds numbers in Chinese culture. Why? Because the Chinese (especially Cantonese) pronunciation of 4 sounds a lot like the same word for die or death.

To stay in a hotel room number 40 therefore would suggest you’re in a room marked by death. To write the floor after the 3rd floor as the 4th floor in the lift console would symbolically suggest you’re going to a dying floor. Better to make it sound confusing with 3A then to risk the ominousness. Likewise (although I haven’t confirmed this yet), many price tags in Chinese-run businesses are not going to include 4 as that has connotations of a transaction whose price is death.

Finally, the rule already shared at the start of this list…

6. Don’t forget to give an ang-pow

If you’re “eligible” to give and there are “qualified” recipients, hey, it’s always nice to do so. Not only for the edifying joy of sharing in a culture but also to prevent the stress to some very traditional folks for whom such customs are taken very seriously.

So there we have it. Six gentle reminders on when, who, what, how and how much to give when it comes to ang pows. These are customs, not laws nor “recommendations” nor opinions nor “regulations.” Negotiating them is part and parcel of what it means to belong in a culture.

One final “rule”: When you receive an ang pow, accept it with two hands ya? (smile)

Happy Chinese New Year, everybody!

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.