KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 24 — Last year, Bollywood blockbuster Padman, a critically-acclaimed Hindi movie on period poverty in rural India, made headlines worldwide for highlighting the issue and the taboos associated with menstruation.

Period poverty is defined as the inability of menstruating women to access sanitary products and safe, hygienic places in which to use them.

In the movie, actor Akshay Kumar plays the protagonist battling the superstition, taboo, criticism and suspicions of his overly pious neighbourhood in trying to get for the women and young girls in his area cheap and accessible sanitary pads instead of the rags they typically used.

The movie shows how menstruating women must segregate themselves from their families and spend the entire period in an isolated area of the house, owing to an ancient religious belief that menstruation is impure.

The movie was made in India, but period poverty is a global issue that affects many countries, including Malaysia, said businesswoman/social activist Zuraidah Daut, 44.

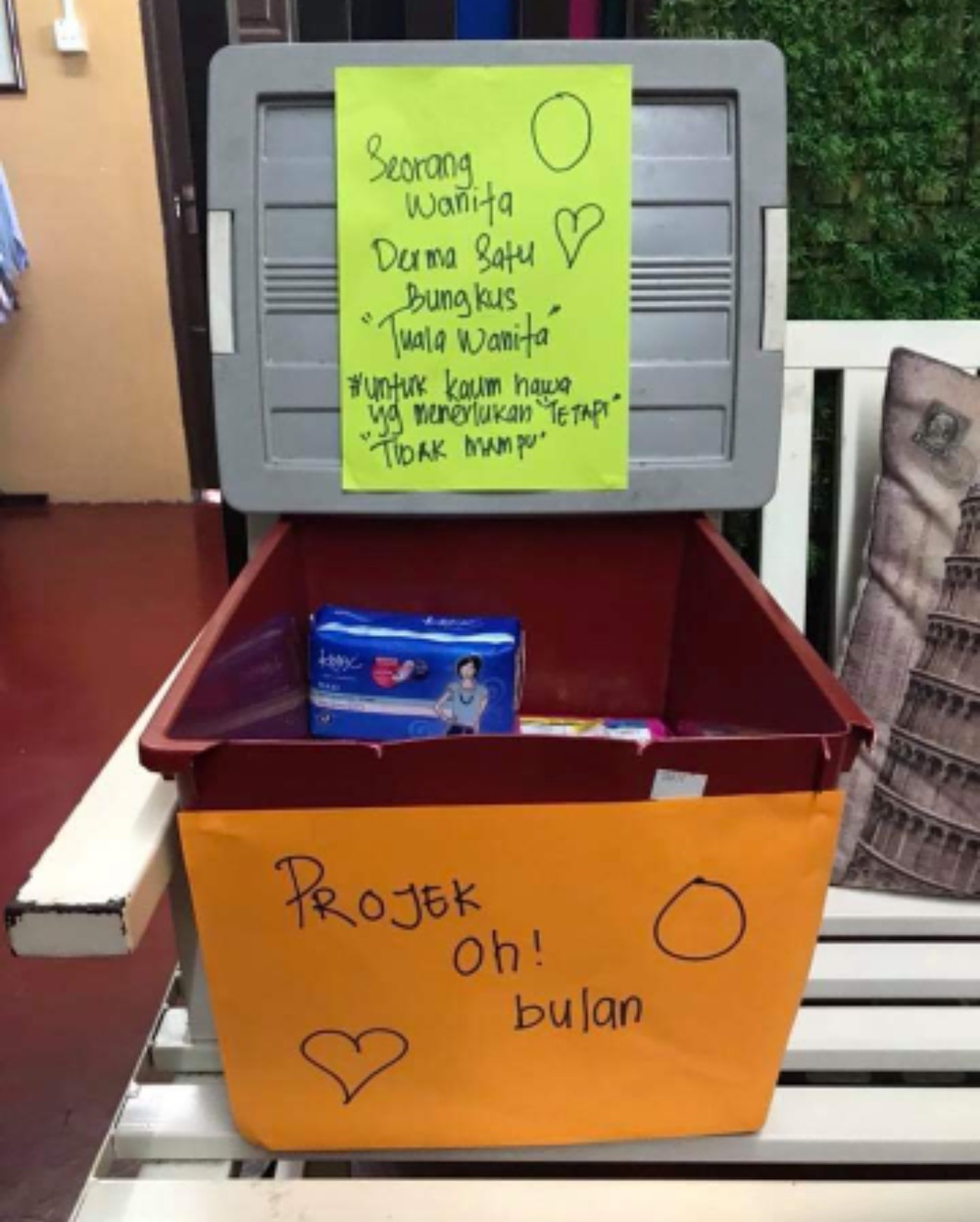

Projek Oh Bulan! — a movement to fight taboos, putting girls back in schools

Zuraidah said she realised the problem after learning about a young schoolgirl who was frequently absent from school.

“When I investigated, I found that the reason she skipped classes, was because of period leakage incidents, and she could not afford to buy sanitary pads,” the Johor native turned Kelantan resident told Malay Mail.

“I was moved to help because I know that it would be extremely difficult for them to go through their menstrual cycle.

“I was worried about their hygiene factor. I do not want anyone, especially male folks, to assume that this is normal.”

Zuraidah launched her project early this year, using Facebook as her platform to spread the message. She also placed boxes in grocery stores, salons and fitness studios, calling on women to donate a packet of sanitary pads each to those in need.

The movement has since gained momentum, with several volunteers joining in to help Projek Oh Bulan! but Zuraidah said it has been challenging to get here.

“At first, the response from those around us was not encouraging, as they were not confident and didn’t trust the idea behind this, but when they were given insights into it and after studying the issue themselves, I received great response and support,” she said.

Perseverance has paid off, however, as sanitary product maker Libresse has also joined her movement.

Libresse has stepped in to aid her efforts by sponsoring sanitary pads for her project in a school.

She said that Projek Oh Bulan! has also allowed almost 80 per cent of students it knew about to overcome the period poverty that had kept them out of school.

“They dropped out because of their families’ dire financial straits. Usually, it’s a case of having too many female siblings,” she said.

Zuraidah is currently focusing her campaign in her area of Pasir Mas, where she works with students from SMK Sultan Ibrahim 2, SMK Kampung Dangar and SK Sultan Ibrahim 3.

“When I checked, I was informed by the teachers that their students were skipping school, because of period leaks. To me, this should not happen. Periods should not be a reason for the inability to unleash one’s full potential and I was determined to see these kids finish schooling,” the mother of eight said.

No official statistics on period poverty dropouts

It is unclear how significant period poverty is in Malaysia as there are no direct records related to it.

Malay Mail’s checks with the Women, Family and Community Development Ministry as well as the Education Ministry showed that neither specifically recorded such data.

The Education Ministry also said statistics on school dropout rates were restricted.

Despite this, National Population and Family Development Board’s (LPPKN) head of reproductive health unit, Dr Hamizah Mohd Hassan recently said it certainly affected women from the B40 group.

She was speaking at a panel titled Moving Forward: Period Poverty After Pink Tax during the Merdeka Menstrual event last weekend alongside Petaling Jaya MP Maria Chin Abdullah and SPOT Malaysia founder Aishah Hoo.

According to ActionAid UK, globally, female students often miss one or more days of school during their periods, affecting their education.

“In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, some girls will miss as much as 20 per cent of their school year; some may drop out of school altogether.

“The loss of education can mean girls are more likely to be forced into child marriage,” it said on its website.

ActionAid said that in Rwanda, many girls miss up to 50 school or working days annually because of period poverty and its associated stigma.

Period poverty is also an issue in developing nations.

According to Girlguiding UK one in 10 girls in the UK has been unable to afford period products.

In 2017, girls’ rights charity body Plan International UK said that one in seven (14 per cent) girls in the UK admitted that they did not know what was happening when they started menstruating, with more than a quarter (26 per cent) reporting that they did not know what to do when they started having their period.

One in 10 were also told not to talk about their periods in front of their mothers (12 per cent) or fathers (11 per cent), with 49 per cent of girls missing an entire day of school because of their period, of which 59 per cent have made up a lie or an alternate excuse.

No more pink tax, but is that sufficient?

The Barisan Nasional (BN) government removed last year the so-called pink tax or taxes on female hygiene products from the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

The GST was repealed last year and replaced with the Sales and Services Tax (SST).

The Pakatan Harapan administration also exempted feminine hygiene products from this.

Women’s Aid Organisation’s (WAO) senior advocacy officer, Natasha Dandavati said the government’s recognition of menstrual products as essential items and removing the pink tax was an important first step in addressing the issue.

However, she said this would not address period poverty without other measures.

“While we don’t have official statistics on the extent of this issue in Malaysia, we do know that girls and women from poorer communities resort to using coconut husk and newspaper in place of unaffordable sanitary products. The B40 community in particular struggles with this issue.

“The lack of access to affordable sanitary products can result in girls from low-income communities dropping out of school, which in turn perpetuates the cycle of poverty and lack of economic opportunities later in life.

“In this way, a failure to comprehensively address the factors contributing to period poverty violate girls and women’s rights under CEDAW and the CRC of equality in health, education, and income-generating opportunities,” she told Malay Mail, referring to the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Dandavati said any effective response to the issue must be multi-sectoral and address the real-world experiences of the women and girls affected.

For example, she said, providing free sanitary products and access to medication for girls experiencing period pain could help reduce their absence from school, as could ensuring access to water and clean and safe bathroom facilities, particularly in rural areas.

“Another approach to tackling this issue could be supporting women-owned micro-enterprises in manufacturing low-cost and eco-friendly sanitary pads that could be supplied to their local communities at a fraction of the cost of these products through traditional manufacturers. Such solutions have been transformative in other countries where period poverty is prevalent, including India,” she added.

The Women’s Centre for Change (WCC) also echoed WAO’s sentiments.

Its programme director Karen Lai, said that the pink tax removal makes little difference, as impoverished women and girls will still not be able to afford sanitary products.

The underlying issue as she pointed out, is one of poverty, which is complex and multi-dimensional.

“While we appreciate the idea behind the Bunga Pads initiative to distribute eco-friendly reusable pads to underprivileged women and girls in East Malaysia, these are not necessarily a comfortable option in terms of ease of use and time consumption involved.

“The government and manufacturers need to work together to devise a practical and environmentally-friendly sanitary product that is easy for women and girls to use.

“Furthermore, schools in urban and rural areas need to upgrade their bathroom facilities to accommodate the comfortable changing of sanitary products. This means ensuring plumbing, clean water, and ample bathroom stalls are available,” she said.

Like Dandavati, Lai also called for the end of all stigmas associated with menstruation.

“Periods should be normalised everywhere, so that girls and women are not shamed for a normal biological function. Parents and teachers need to work harder and more diligently to educate children, regardless of gender, about their bodily functions,” she said.