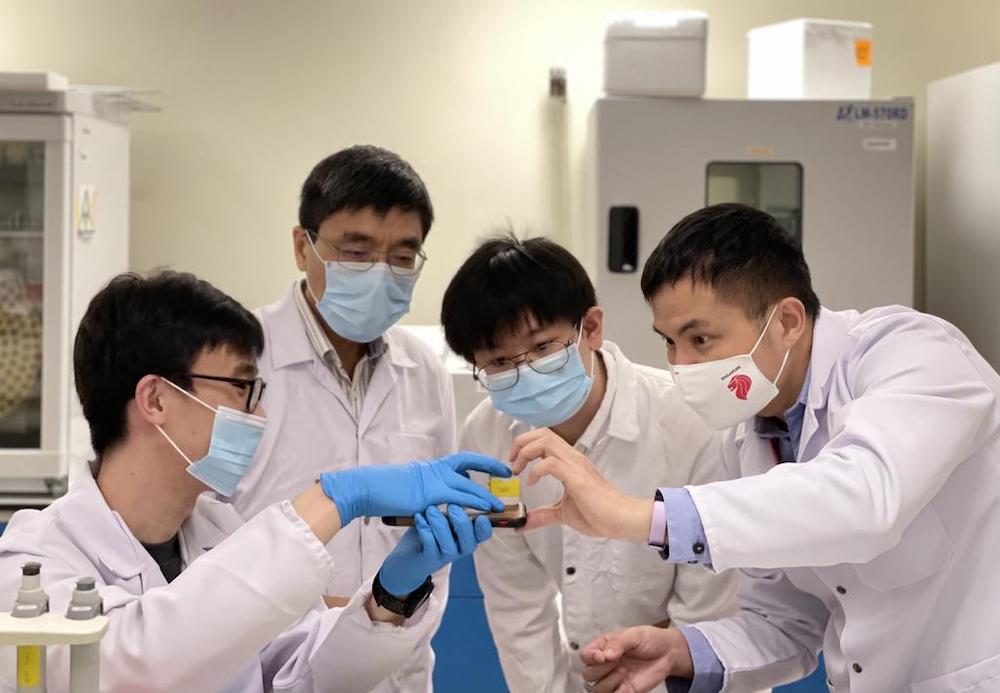

SINGAPORE, March 29 — Scientists at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have developed a diagnostic test for the virus that causes Covid-19 even after it has undergone certain mutations, unlike some other tests whose ability to detect the virus may be impeded by genetic sequence variations in new strains.

Outlining what is believed to be the first rapid test that can do so in Singapore, Associate Professor Tan Meng How, who led the study, said the test takes up to 30 minutes to produce results — slightly longer than the antigen rapid tests (ART) often used for pre-event testing here.

However, the NTU test is 10 times more accurate than the ART, he added during a media briefing on Monday (March 29).

Viruses constantly change through mutation and new variants are expected to occur over time.

Multiple variants of the Covid-19 virus, known as Sars-CoV-2, such as the variant called B117 in the United Kingdom as well as another variant called B1351 in South Africa — both reportedly markedly more infectious — have been circulating globally, Assoc Prof Tan noted.

The new test, called the Vanguard test — short for variant nucleotide guard test — makes use of a gene-editing tool known as Crispr used widely in scientific research to alter genome sequences and modify gene function in human cells, to programme enzymes that can react to the Covid-19 virus or its variants.

The test relies on the reaction produced by this enzyme, which acts like “a pair of molecular scissors”. It is programmed to target specific segments of the Covid-19 genetic material and snip them off from the rest of the viral genome.

Successfully snipping off segments is how the enzyme detects the presence of the virus.

When the coronavirus or one of its variants is detected, the programmed enzyme also becomes “hyper-activated” and starts cutting other genetic material detected in the sample, including a molecule tagged with a fluorescent dye that is added to the sample.

Assoc Prof Tan, who is also from the Genome Institute of Singapore at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (A*Star), explained: “If the virus is present, the molecule will glow. If not, it means the virus is not present to cause the hyper-activation of the molecular scissors.”

So far, the test can recognise up to two mutations within the target sites on the Covid-19 genome, he added.

Rapid tests such as the Vanguard test or the ART, however, are still less accurate than the gold standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, which requires purification of RNA in a lab facility and can take hours to complete.

But in terms of cost, it is significantly cheaper than the PCR test and is similar to the ART, said Assoc Prof Tan.

“There is no rapid test that can outperform PCR in terms of sensitivity. So the question is, can we replace other rapid tests?” said Assoc Prof Tan.

This comes down to the trade-off that each regulatory body is willing to make, whether it is speed or sensitivity of testing that is more critical, he added.

Making the test easy to use

To make the test easier to use, the team integrated the test into a paper strip that looks similar to a pregnancy test.

To test for the virus, the paper strip will be dipped into a tube containing the viral load and enzyme and placed in a heating device at 60°C for 30 minutes.

If the virus or its variant is present, two bands will appear on the paper strip. In the absence of the virus, only one band will appear.

The team also developed a mobile phone app to facilitate the interpretation of the paper strips.

Assoc Prof Tan said the team is looking to refine this diagnostic kit to make it self-contained.

“In a commercial form, it’s not a good idea to have the sample in the tube because if it’s an infectious one, nobody really wants to open a tube,” he said.

In order to deploy the Vanguard test in pre-event settings, where quick results are paramount, the team is looking for more clinical partners to conduct clinical evaluations and to obtain regulatory approval from relevant authorities within the year. It has collaborated with only one public hospital to date.

Assoc Prof Tan acknowledged that the test has its limitations as the virus may mutate into something completely different, which will require the team to design an entirely new test.

“What we set out to do is to give us this time buffer so that if it’s right at the beginning of evolution and we catch it… that will hopefully buy a bit of time to recognise that the virus is mutating here and redesign the test.” — TODAY