AUGUST 24 ― I tried to reassure a lung cancer patient ― who receives free doses of crizotinib (brand name Xalkori) on a patient assistance programme ― that the Ministry of Health (MOH) had promised to retain existing patient access schemes like his, as it was only suspending two new applications by pharmaceutical companies for the programme.

The extremely expensive targeted therapy drug my reader takes is unavailable in public hospitals as it is not listed in the national formulary.

He was diagnosed seven years ago but says he can live a normal life because of the medicine he takes, putting bread on the table for his family without plunging them into financial distress.

Despite the government’s reassurance, he was still fearful that MOH might stop existing patient assistance programmes anyway. He also pointed out that his cousin with lymphoma was on a waitlist and would only get sicker pending MOH’s review.

“Cancer patients have no time,” he told me. “Only thing that stands between us and the Almighty is the medication.”

Health director-general Datuk Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah said patient assistance programmes, or patient access schemes (PASc), that involve the provision of free drugs tied to medicine purchases by the government are feared to be unethical.

He said this was because the giving of free medicine is not recorded explicitly in purchase records between pharmaceutical companies and MOH facilities.

While improving transparency is always a good goal, MOH’s guideline on the submission of proposals by pharmaceutical companies to set up a PASc already appears to tightly regulate patient assistance programmes.

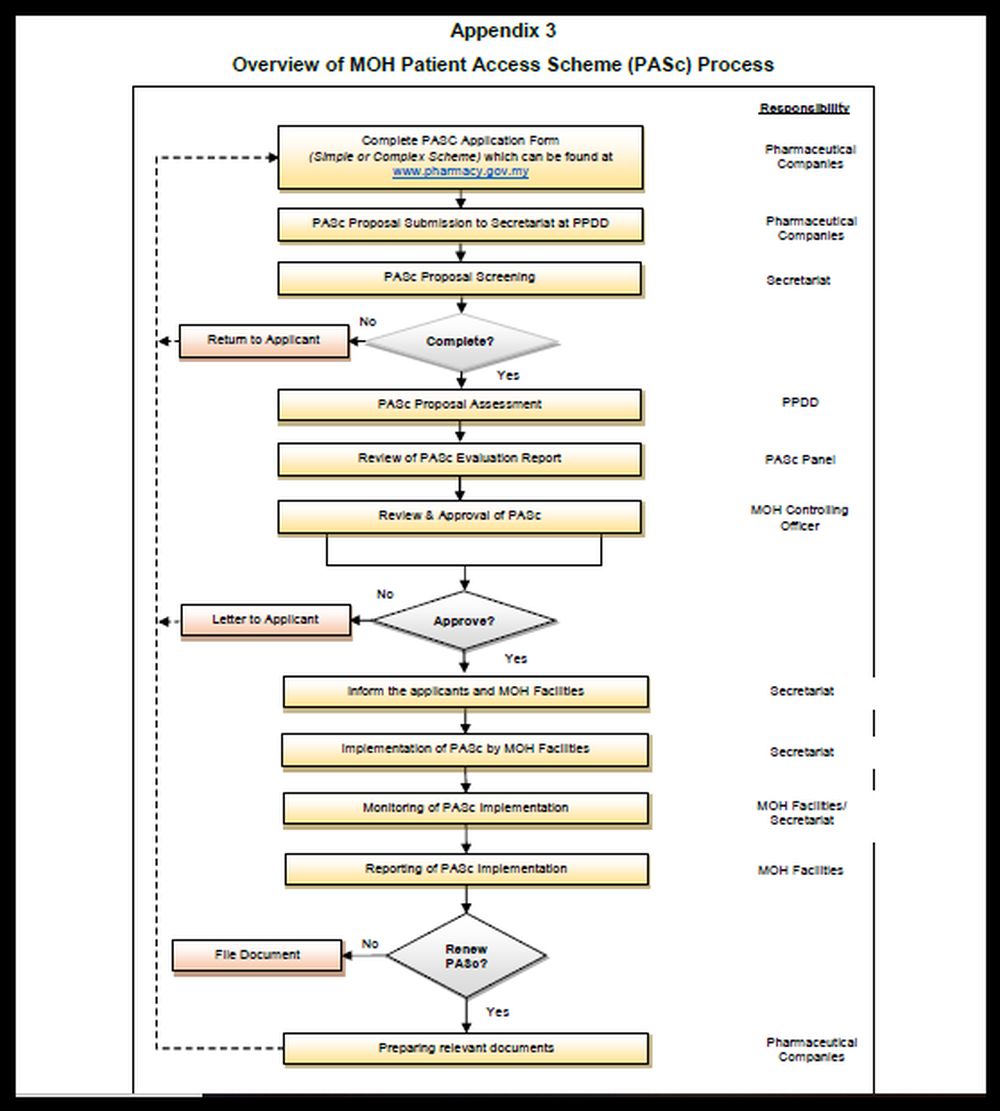

The MOH guideline shows a lengthy diagram on the PASc application process. The PASc application form also requires a lot of details, asking pharmaceutical companies their rationale for the scheme, how the scheme will operate, the criteria in selecting patients for the programme, the number of patients who will be treated with the drug, the market share for the treatment, the market shares of other drugs that will be affected by taking up the treatment, how the scheme will be monitored, how the drug meets an unmet need, and how it will ensure financial benefits for MOH.

“Schemes must be transparent, clinically robust, plausible (credible), practical and have no unreasonable incentives,” says the MOH guideline.

It is not as if pharmaceutical companies are giving free drugs willy-nilly to whoever they like in secret arrangements with specialists after selling other medicines to MOH. Patient assistance programmes, according to MOH’s stringent guideline, must be approved by the ministry.

So why did MOH suddenly decide to review the PASc and suspend two new applications? Did MOH’s SOP fail? Was there an incident of abuse?

Two applications may not seem a lot, but I was told about concerns from a cancer organisation who feared that up to 1,800 patients could be affected. That is only from one organisation; there are many other patient groups dealing with different cancers.

MOH should be more transparent and explain which step of its complex PASc application procedure is problematic.

MOH also made a rather peculiar statement, saying it was fine with pharmaceutical companies giving free drugs to patients as long as they were not given on condition of purchases by the ministry.

What is wrong with a buy one-free one kind of scheme?

Why should any company ― pharmaceutical or otherwise ― give away products for free without something in return, be it actual sales or potential future sales? Businesses are not charities.

If MOH is against patient assistance programmes, it should negotiate tougher with pharmaceutical companies to get cheaper drugs listed on its formulary. But at the same time, the government should be careful not to violate intellectual property rights that could hurt foreign investment in the country as a whole and, ultimately, public health spending, such as the compulsory licensing of Hepatitis C treatment sofosbuvir.

While MOH deliberates on the PASc, my reader fears losing access to crizotinib, an expensive personalised medicine which is unavailable in public facilities in Malaysia, but is available on the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) successfully negotiated discounts for the oral treatment from Pfizer in 2016.

NICE, which provides advice and guidance to the NHS, managed to get Pfizer to twice reduce the list price of £51,000 (RM270,513) per patient per course of treatment. Crizotinib targets a specific genetic mutation known as ALK-positive, reportedly present in only 5 per cent of patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

However, this is not to say that there are no concerns about patient assistance programmes.

Pharmaceutical companies should be far more transparent about these schemes and detail exactly how many people are on their patient assistance programmes, their financial eligibility requirements, and the application process.

A 2009 study by Niteesh K. Chodhry et al noted that if only a few people could successfully go through the complicated application processes for manufacturer-sponsored patient assistance programmes that are touted as a “safety net”, then public reliance on them may be misplaced. But if such programmes were widely used, then this highlighted the deficiencies of the public health care system.

According to Dr Rishi Sachdev and Dr Yousuf Zafar from Duke University, payers argue that financial assistance programmes for patients disrupt market forces, since cost-sharing designs created by insurance companies are made irrelevant, and may result in insurance providers inaccurately pricing risk in future cases. So costs could go up in future.

They also argue that patient assistance programmes don’t actually lower the price of drugs because of cost shifting by payers that results in higher premiums for everyone, while individual patients are shielded from bearing the full cost.

Or patient assistance programmes may even lead to higher drug prices because drug manufacturers would be motivated to raise prices if patient demand was less sensitive to price, as David Howard from Emory University argues. He pointed out that drug prices dropped by 10 to 26 per cent in 1989 in Germany after patients were required to pay higher out-of-pocket costs for drugs that cost more than similar therapies.

He also raised insurers' and payers’ concern that patient assistance programmes turned patients away from generics and cheaper alternatives to new, patent-protected treatments.

While we debate the merit of patient assistance programmes, we should remember that cancer patients are running a race against time.

MOH should also consult stakeholders before arbitrarily making major policy decisions that cause unnecessary anxiety.

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.