KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 8 ― The unassuming Kwong Fook Wing tailor shop that still uses traditional sewing machines marked 100 years of operations last month, boasting of the royalty and Malaysia’s second prime minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein among its illustrious clientele.

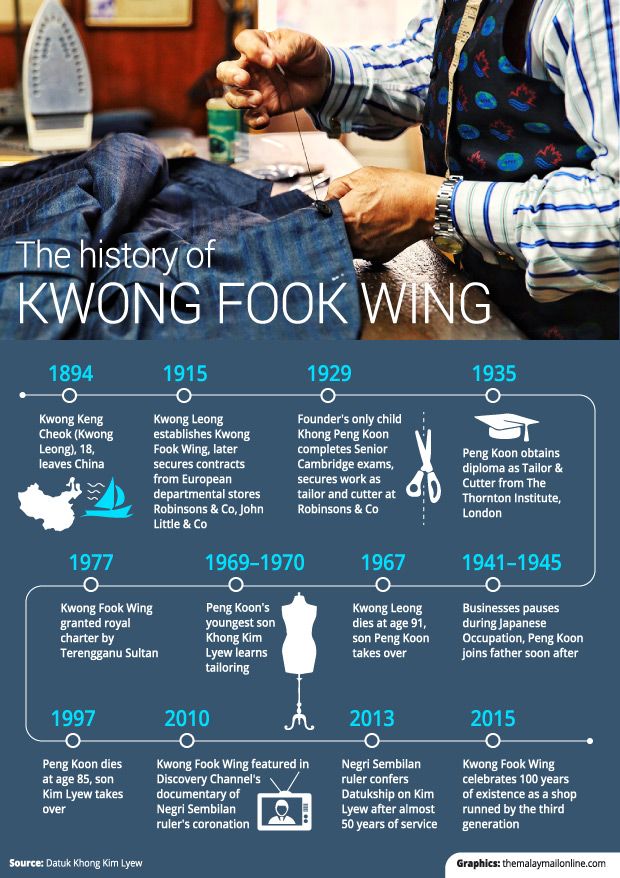

Kwong Fook Wing owner Datuk Khong Kim Lyew said the one-century milestone was his dream for the small tailoring outfit and a fulfilment of his late grandfather Kwong Keng Cheok’s legacy when the latter started the business in 1915, 21 years after leaving Chung Woh village in Guangdong province, southern China, as an 18-year-old.

“But we are very proud that we have gone through a hundred years and the ownership of the business is still in the family's hands,” Khong, the third-generation proprietor aged 67, told Malay Mail Online in a recent interview.

Khong compared his shop in Jalan Sultan ― in the city centre area known in modern times as Chinatown ― that currently hires around five tailors, to bigger and older firms that no longer remain in the hands of the founders’ families.

He said he was unsure of the exact date when his grandfather started Kwong Fook Wing in 1915, but the tailor shop celebrated its 100th anniversary on October 3.

Despite lacking formal education, Khong said his grandfather ― who once laboured as a rickshaw puller for two years in Singapore ― had the foresight of future demand for western suits in the British colonial days and took up tailoring skills, pouring his savings after years of hard work into opening a tailor shop.

Khong’s grandfather also sidestepped worries that European clients may not want to use the services of a Chinese-owned shop by getting contracts to sew suits from Kuala Lumpur’s then top two British-owned department stores, John Little & Company and Robinsons & Company.

Through such shrewd business acumen and reputable workmanship, Kwong Fook Wing ― which is a combination of the founder’s surname and the Chinese characters for wealth and glory ― thrived well and attracted clients such as British colonial administrators, royalty, Malaysian Cabinet ministers and senior civil servants.

“Of course, before Independence, we also had a lot of local dignitaries like Tun Tan Siew Sin, Tun Ismail and later on, we had suits made for Tun Abdul Razak and the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. That's how we have been able to carry on for the last one hundred years,” he said, referring to the country’s first minister of commerce and industry, second deputy prime minister and second prime minister.

Khong said “anybody who is somebody” would have came to Kwong Fook Wing to have their clothes made before and after Malaya achieved independence in 1957.

Never intended to tailor

Carrying on a trade that his grandfather passed on to his father Khong Peng Koon, Khong confessed that he never started out with the intentions of becoming a tailor and only ended up doing so due to filial piety.

Khong had a short stint in the army after his Form 5 studies, but deserted the army to continue his Form 6 studies. He completed his Higher School Certificate in 1968 with the intention of going to university.

“I was admitted to the Universiti Malaya in 1969 at the time of just before May 13, at the time most of my brothers were away from Kuala Lumpur, and I felt at that time it was better for me to stay with my parents. I am the only son around, so that is why I stopped my studies in Universiti Malaya and came back to help my father in the shop.

“But actually education was really what I wanted. I had no intention to become a tailor,” he said, acknowledging however that he was not really interested in the arts course in UM, nor in his subsequent social sciences course.

In 1970, Khong applied to the then-University of Penang (now Universiti Sains Malaysia) and was offered a place in social sciences, but again stopped midway as a youth aged around 21 to help his father who was already in his 60s then.

“But again, I sort of give (sic) up because my mind was not on studies; I was all the time thinking whether my father would be able to carry on alone in the shop, so I stopped and came back. And from 1970, I was helping and understudying the art of cutting and tailoring from my father,” said Khong, the youngest of seven sons.

Khong has continued the trade until today, taking over the business when his father died at 85 in 1997.

Disrupted during Japanese occupation

Khong did not recall the tailor business having to face many major challenges as his father had built up a regular client base, saying that the shop was not affected by the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis.

Business was disrupted during the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945 as there was no demand for tailored clothes at a time of food shortage when people ate tapioca to survive, Khong said.

Business was disrupted during the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945 as there was no demand for tailored clothes at a time of food shortage when people ate tapioca to survive, Khong said.

The only time when the shop faced a shortage of material was immediately after World War II, owing to low production in England that was then the supplier of Kwong Fook Wing’s sewing materials, unlike today where they source from everywhere including Italy, Japan, Korea and China, he said.

In the first few days of the riots that broke out on May 13, 1969, Kwong Fook Wing was closed like all businesses in Kuala Lumpur. The tailor shop then followed the curfew hours that were slowly removed after some months, Khong said.

Surprise visits by PM, rulers

Khong’s anecdotes of his 45-year career spoke of “simpler” times when official and royal protocols were not much of a concern.

“When I was serving the prime minister Tun Razak, we always have fittings done in his official residence.

“But one fine day, without notice and without announcement, his car stopped in front of our shop (then) in 60, Jalan Sultan, which is down the road, and he came down and told me and my father: ‘Well you have been coming to do suits for me. Since I am passing by and they told me your shop is here, I must come in and look at your shop’,” he said, also recounting fondly that he and his father were served tea and kuih before fitting sessions at the late Abdul Razak’s house.

The Sultan of Terengganu who had served as the fourth Yang di-Pertuan Agong also once dropped by at Kwong Fook Wing unannounced one day for a brief visit, while the Kelantan Sultan who had served as the sixth Yang di-Pertuan Agong had also visited the shop.

“When he came to the shop, there was no protocol at all,” Khong said, referring to the Kelantan Sultan.

“He just came in with one policeman not in uniform as his bodyguard and he sits down and chit chat like an ordinary person. He would go into the workshop and say hello to the tukang (craftsman). When he sees my mother doing stitching of buttonholes, he would say a few words, ‘Nyonya ada baik’ (How are things, Nyonya?). So this was the simple way of life those days,” he added.

Khong estimated that Abdul Razak ― the sole prime minister that he had served ― ordered an average of three suits every month in the last five years of his life, confirming that he had only tailored clothes for the prime minister’s sons ― including current Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak ― when they were young.

A year later after Abdul Razak died in 1976, Kwong Fook Wing was granted a royal charter by the late Terengganu Sultan Tuanku Ismail Nasiruddin Shah, while Khong was granted a Datukship by the Negri Sembilan ruler whom he had been serving for almost five decades. Khong had also appeared in a 2010 documentary aired by Discovery Channel on the Negri Sembilan ruler’s coronation.

Fancy a RM2,000 bespoke suit?

Khong said he does not mind who his customers are, as long as they are prepared to pay an average price of between RM2,000 and RM3,000 for a suit.

Although business has slowed slightly as demand shifted over the years to ready-made clothing and branded suits, Khong noted that a younger set of internet-savvy clients has begun to show appreciation for tailored suits.

“I would say all these are up and coming executives in their late 20s and early 30s. So they want to appreciate (bespoke tailoring) and most of the time, they know what they want and we hope to give them what is demanded by them,” he said, describing the long process to make a bespoke suit that features hand-sewn buttonholes and hand-stitched buttons.

Khong said although his business still enjoys healthy demand, he is getting older and has to turn down some orders due to the attention required for each garment to be properly cut and fitted.

No successor identified yet

He said no successor has been identified to take over Kwong Fook Wing, noting that the younger generation is not keen to take up such a trade as it means hard work and long hours.

“Unfortunately, times have changed, circumstances are different, so I don’t think there will be a fourth generation within the family to carry on this business.

“Most of the other members of the Khong family after me have gone to the university and when they finish their tertiary education, they are more interested to pursue careers of their own,” said Khong, who has three daughters.

Khong recalled few holidays for the tailor shop in the past, with his father usually opening at 8am and shuttering at 8pm, while workers who lived in the shop worked longer hours.

“Even after the shop is closed, some of the workers could be working up to 10 o'clock and then finish their work, and then they sleep in the shop itself. But these days, circumstances have changed. People no longer are that hardworking and people are no longer as loyal as earlier people. Mobility is more frequent now,” he said.

Khong’s staff have stayed with the tailor shop for a long time, with an assistant in his shop still working there after almost 40 years. The longest-serving employee came in at 17 and worked until two weeks before his death at 93 in 2003.

Although much history has been made in the years of Kwong Fook Wing’s operations, Khong does not think that people would be “interested in just a little tailoring business as a museum” or would want to spend time looking at some of the old things left behind, including an almost century-old scissors belonging to his grandfather that is still functional.

“Well, I have been approached by the Chinese society to hand on some of my things to them and they would devote a little bit of space to exhibit some of these old tailoring things. But I said I am not finished yet. When I am finished, I may think about it, I still have use for some of these things.

“If my health permits, I will carry on for as long as I can,” he said.

Kwong Fook Wing

51, Jalan Sultan, 50000, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Opening hours:

Mon-Fri, 9am-6pm

Sat, 9am-3pm

Closed on Sundays.