KUALA LUMPUR, Feb 14 — One man’s meat is another’s poison. In the world of global scrap trade, a more fitting maxim could well be: one country’s trash is another’s treasure.

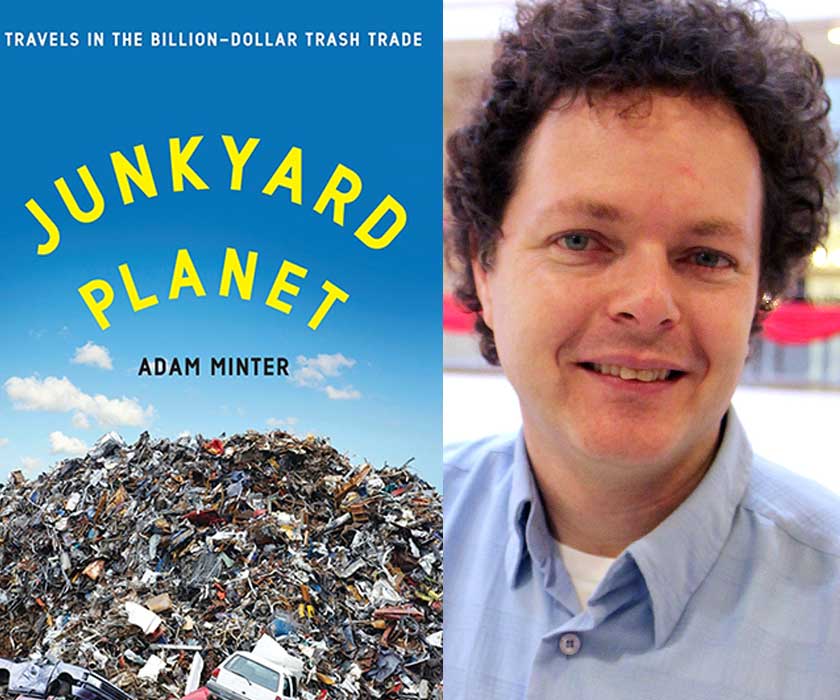

In his new book Junkyard Planet, journalist Adam Minter uncovers the secrets of globalised recycling -– from the cast-off Christmas tree lights of America to the giant scrapyards and recycling centres of China.

Be it metal, plastic or paper: every reusable and recyclable part is stripped away and resold or converted into valuable raw material. Junk is big business.

“Growing up” in a junkyard

Minter, currently a Bloomberg World View columnist based in Shanghai, is no stranger to the scrapyard industry. He explains, “I grew up in Minneapolis in a junkyard family. My father was a scrapyard owner and my great-grandfather was a Russian Jew who used to pick garbage off the street to sell when he first came over to America. He was a self-made man.”

As a young man, Minter would receive “junkyard lessons” from his grandmother whom he would work closely with. He says, “She taught me that you make your money when you buy, not when you sell. If you don’t know the value of something that you are purchasing, then you are already making a loss. We have to see value where others don’t.”

Given his background, it was serendipity when he first visited China in 2002; the economy was growing rapidly and consuming more and more resources. A good chunk of these resources came from recycling exported scrap –- be it old cell phones, computers or automobiles.

“No one was covering the recycling industry in China back then and news outlets were hungry for such stories. I was very lucky to be in the right place at the right time.”

An outsider with an insider’s view

During his visits to various scrapyards in China, Minter benefited from his insider’s understanding and appreciation for the people who performed tasks often seen as menial.

“It’s not pleasant work, this labourious process of sorting out the useful scrap from the useless. I had done the work myself back in my father’s scrapyard, so I see these workers as equals and professionals.”

He observes that the process is very efficient in China, and conducted with a greater level of expertise than in Western countries.

“These are experienced workers who can separate very similar metals such as zinc and aluminium by sight and feel alone. It’s amazing how quickly and precisely they can do this. In the US or EU, they would rely more on machinery.”

Surely, then, it is thanks to the cheaper labour costs in China that it has become the world’s top export destination for scrap? Minter believes the answer isn’t as straightforward as that.

“While the lower labour costs does help, why isn’t Sudan or some country in Sub-Saharan Africa, where it is cheaper still, an even larger recycling hub? China’s unique position comes from the fact that it is also a manufacturing giant that desperately needs these repurposed materials to create more products.”

How a shoebox gets recycled into... another shoebox

Minter offers an example of how recycling works: “When you buy a pair of branded sport shoes, they come in a cardboard shoebox. Where does that box go? It gets thrown into a recycling bin in the US, Japan or EU. That box then gets shipped to China where it will be recycled into a new cardboard box, probably another shoebox... and then shipped back to where it was first thrown away!”

How could shipping something to the other side of the world to be recycled be environmentally friendly?

“The worst recycling is still better than none; it’s definitely better than digging mines and clearing forests. By not tapping into our natural resources directly, this is better for the environment.

Recycling also usually consumes 85 to 90 per cent less energy than mining resources directly.”

Recycling plays an important role in the global economy. For example, more than 50 per cent of the world’s steel supply comes from recycling. The process helps to maintain the supply chain, and to keep global prices of materials and end products stable.

Minter notes that sending one’s garbage to the other end of the world to be processed can actually be more cost-effective than domestic recycling.

“Manufacturers in Shenzhen often compete to get containers to the US, which can cost US$2,500 per container. But there is nothing to send back as American manufacturers don’t export much to China. As the shipping companies must send these containers back to China to complete the cycle, they heavily discount the return trip. So scrapyard merchants can send scrap to China for as low as US$300 per container!”

Note: One US$1 is about RM3.33.

He adds, “By contrast, if the same merchant were to transport this scrap by truck or rail, say from Los Angeles to Chicago, it could cost up to US$2,500. That’s more than eight times the price of shipping it to China!”

The end of junk

One question Minter always gets asked is whether there is a better solution to this globalised recycling.

Can there be an end to junk?

“To me, the best solution is simply to extend the lifespan of the things we buy. When we buy cheap, we buy twice. So while it may hurt your wallet when you purchase something more expensive, it’s worth it in the long run as it lasts longer and you don’t have to replace it as often.”

But isn’t there a trend for built-in obsolescence in products these days?

“That’s true. However, manufacturers are also starting to respond to demand for more long-lasting products or by making products easier to recycle. They really have no choice as the world’s population continues to increase but resources are rapidly dwindling.”

For example, Westron, an automation and electronics manufacturer, has started an in-house recycling department for their products; this way they can control their own raw material supply.

Minter adds, “Ultimately, if we really want to make a difference: don’t buy something in the first place.

There will be no need to recycle if no one buys stuff in the first place. So long as we want to consume products, we will need to recycle. Junk won’t go away.”

As to prove his point, he takes out his smartphone and admits, “Of course, I’m as guilty as the next person. I’m a consumer too.”

This story was first published in Crave in the print edition of The Malay Mail on February 13, 2014.