KUALA LUMPUR, July 6 — Outgoing United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, has criticised the new government of performing a “backflip” on its predecessor’s commitment to take poverty seriously.

In Alston’s 19-page final report, he outlined the many findings he made when conducting his survey here in August last year, pointing out the main problems that lie with the country’s poverty measure benchmark and for the lack of transparency and forthcomingness with data and information.

“Malaysia’s new Government has performed a backflip on its predecessors’ commitment to take poverty seriously,” said Alston in a statement.

Alston said government officials, including the then-prime minister, had committed to revising the national poverty line, but the current government’s response to the final report has thrown that commitment into doubt.

Pakatan Harapan and its prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad was in power when Alston visited. They have since been replaced by the Perikatan Nasional administration led by Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin.

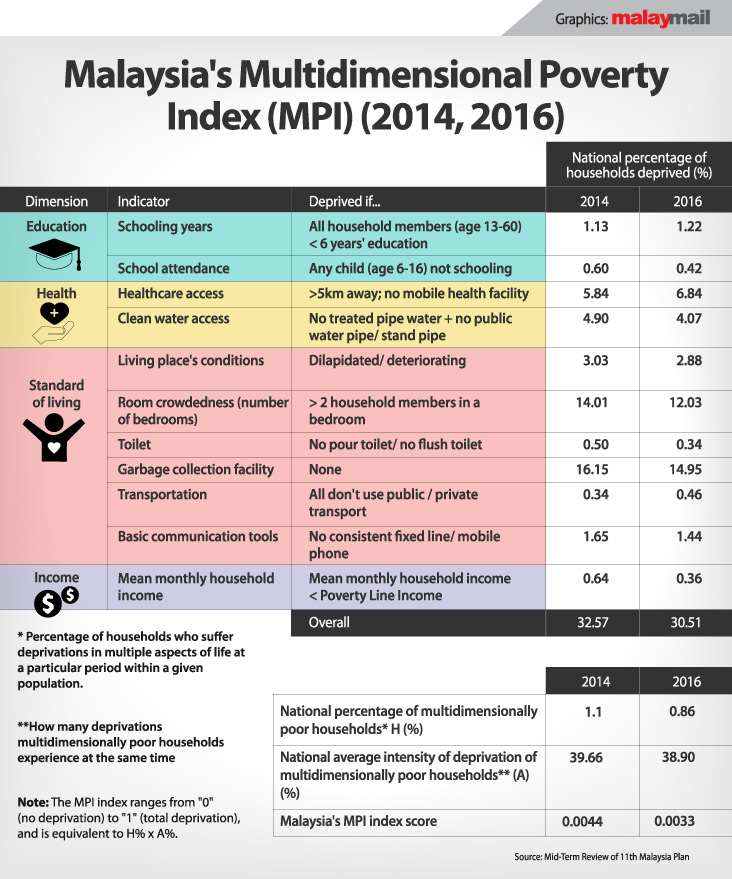

Alston had called Malaysia’s claim of having a national poverty rate of only 0.4 per cent, which would rank it among the lowest in the words, as a “statistical sleight of hand”.

“Malaysia has achieved extraordinary economic growth over many years and made great strides in reducing poverty. But its official method of measuring poverty produces a national poverty rate of just 0.4 per cent, the lowest in the world, suggesting that less than 25,000 households are in poverty.

“Malaysia has achieved extraordinary economic growth over many years and made great strides in reducing poverty. But its official method of measuring poverty produces a national poverty rate of just 0.4 per cent, the lowest in the world, suggesting that less than 25,000 households are in poverty.

“At the end of his mission, the Special Rapporteur observed that this would make Malaysia the unrivalled world champion in conquering poverty.

“But he also noted that the claim reflected a statistical sleight of hand that has had extremely harmful consequences,” read an excerpt from his complete and final report.

Alston said the new government remaining adamant in standing by its absolute poverty rate was deeply concerning, as the line is inadequate, and almost universally considered to be misleading.

“The government’s protestation that it is ‘derived from internationally accepted standards’ is a smokescreen and ignores the blatant mismatch between reality and statistics.

“Pretending that almost no-one in the entire country lives in poverty doesn’t change the reality that millions are poor. Saving face is one thing, but distorting the facts is quite another,” he wrote.

Alston did commend Malaysia on making headway in combating poverty over the last 40 years, but said the job was far from over, adding that despite significant growth by the bottom-40 per cent of society a considerable proportion of the country still lives below their means.

He pointed out how the current absolute poverty line of RM980 per month for a household of four, which rounds up to about RM8 a person per day, was grossly low for a country on the cusp of attaining a high income status.

“However, during the course of the visit officials consistently claimed that poverty had been virtually eliminated, with only ‘pockets’ remaining,” he wrote.

However he chided the country’s approach and position on data collection and transparency, pointing out how the administration’s refusal to provide full access to key household survey micro data, unlike neighbouring countries, is stifling both public and private research and analysis efforts on poverty and inequality.

However he chided the country’s approach and position on data collection and transparency, pointing out how the administration’s refusal to provide full access to key household survey micro data, unlike neighbouring countries, is stifling both public and private research and analysis efforts on poverty and inequality.

Alston himself admitted going through difficulties when trying to obtain official data from government agencies, namely the Department of Statistics, as similarly experienced by other international organisations and researchers.

“A representative of the Department of Statistics said that the Department ‘makes the data available to all’, while an official of the Ministry of Economic Affairs said the Government provides what it can, but must be careful with data owing to privacy concerns.

“Since many other countries provide anonymised data without compromising privacy, the policy seems more likely to be motivated by a desire to conceal from the public information that might not be favourable to the Government,” he wrote.

He added how the reactions of government officials suggested that key data and information was not even being collected, going further saying they were even unable, or sometimes unwilling, to provide estimates of statistics and numbers sought by Alston.

Besides sticking to an outdated poverty measuring system, Alston also highlighted the country’s sidelining of indigenous and the exclusion of foreigners when taking into account these income figures.

Concerning the indigenous, Alston observed that despite commitments by the government and political figures, the rights and way of life of these people are still misunderstood, oftentimes dismissed by the government and excluded from health, education, and social services.

He also pointed out how the administration allowing for indigenous land to be declared forest reserves before being cleared for commercial development was a clear indication of the country’s leaders’ lack of understanding their ways of life, their beliefs, and how it affects their cultivation methods, diet, shelter, and traditional health care remedies.

Other areas that could do with improvements, recommended by Alston, is the country’s treatment towards migrants, stateless people, refugees, and even for it to recognise that its decisions on agricultural and commercial rural developments must take into account real effects of climate change.

As recommendations, Alston urged the government to urgently adopt a more meaningful poverty line, consistent with international standards which is inclusive of the vulnerable and non-citizen populations.

“Policies in key sectors should be adjusted to specifically address the needs of the lowest 15 to 20 per cent of the income distribution, who are widely considered to live in poverty.

“The government should adopt a comprehensive data transparency policy and make anonymised microdata available to researchers.

“Overall spending on social protection needs to be significantly expanded,” he wrote as part of his recommendations.

Alston added that the current arrangement of several social protection programs spread across many ministries were poorly coordinated, heavily siloed, and often ineffective.

“They should be replaced by a social protection floor reflecting the ILO (International Labour Organisation) approach,” he added.

Alston, during his visit here travelled to Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, Sarawak, Sabah, and Kelantan, and met state and federal government officials, international agencies, civil society, academics, and people affected by poverty in urban and rural areas.

He visited a soup kitchen, a women’s shelter, a children’s crisis centre, low-cost housing flats, a disability centre, indigenous communities and informal settlements and schools.

Alston was rapporteur between 2014 and 2020, and has been succeeded by Olivier De Schutter.

Putrajaya has yet to respond to Alston’s report today at the time of writing.